An exhibition holds universal truths about the fragility and power of the skin and bones we occupy

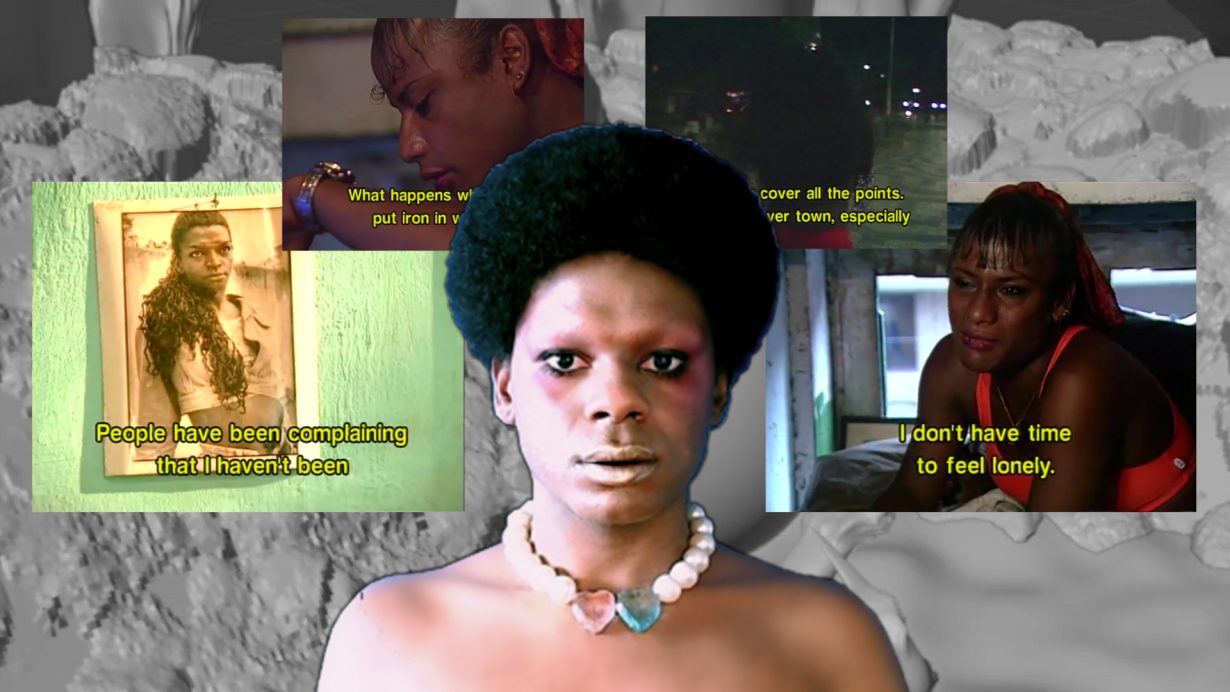

In her video essay, Notes on Travecacceleration (2021), an animated avatar of the Brazilian artist Ode says “My travesti identity makes me and other people like me be considered subhuman: however, we also reinvent ourselves as inhuman and antihuman.” The narration is interspersed with found footage depicting slavery, segueing into old news interviews with gender non-conforming street people and ending with the new visibility being afforded trans people in the contemporary media-landscape globally. With a nod to American curator Aria Dean’s 2017 essay ‘Notes on Blacceleration’, Ode posits that, accelerationism – that is the idea of accelerating capitalism and technological change to arrive at the disintegration of neoliberal hegemony sooner than might otherwise be the case – has always been implicit in trans and non-binary identity.

The just under five-minute film lends its title to an exhibition staged both at Lux’s gallery space in London and on the arts agency’s website, curated by the Ode and featuring the sound and moving-image work of seven of her Black, trans peers from Brazil. Collectively their work builds on Ode’s video as interlinked narratives emerge addressing the broad themes of racism, transphobia, body politics, capitalism and colonialism. The aim, for Ode, is to lean into the antihuman and monstrous, embrace it as ammunition to better “shatter the taxonomies that capitalism uses to racialise, sexualise and classify identities to better exploit them.” Approximately half the works are theory-heavy and essayistic: Jota Mombaça’s two-and-half-minute Morar na Indefinição (2018) consists of an interview with the artist as she sits on a garden bench, the tranquil setting at odds with her blunt proclamation that “peace is not an option” for the Black trans person. The only possibility – a radical, emancipatory action – is to “to live in indefinition.”

As well as Dean, Ode’s work is constructed on foundations built by philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari and, to a point, Nick Land, yet elsewhere in her exhibition there is a welcome exploration of how identity can be discussed without relying on the framework of Global North academia, itself a colonising force. In a sound work by Maria Clara Araújo, “Travesti” não se traduz! (“Travesti” does not translate!, 2017), the artist explains “travesti is a Latin American identity and to say this means that the particularities and specificities of being a Brazilian travesti turn this identity into something unique worldwide.” Within Brazilian Portuguese trans and travesti identities are separate concepts, the latter incorporating a far wider social and cultural context in which class, race and national identity intersect. Araújo continues “It is much more worthwhile that we present ourselves to the world without translation. Because why do we often need to translate ourselves, you know? For the white man to understand us.”

Yet while Brazil has a vocal trans and gender non-conforming population, contemporarily and historically, it also has the highest trans murder rate in the world: in 2020, 175 trans women were murdered in the country. In the narrative of a ten-minute video, E se começarmos a ver a colonização como uma infecção (And if we start seeing colonization as an infection, 2020), Bruna Kury explores her own body through photographic portraiture and animated renderings of the biotech procedures used in a medicalised gender-affirmation process, and throughout which the artist posits cis-gender dominance as a product of colonial violence.

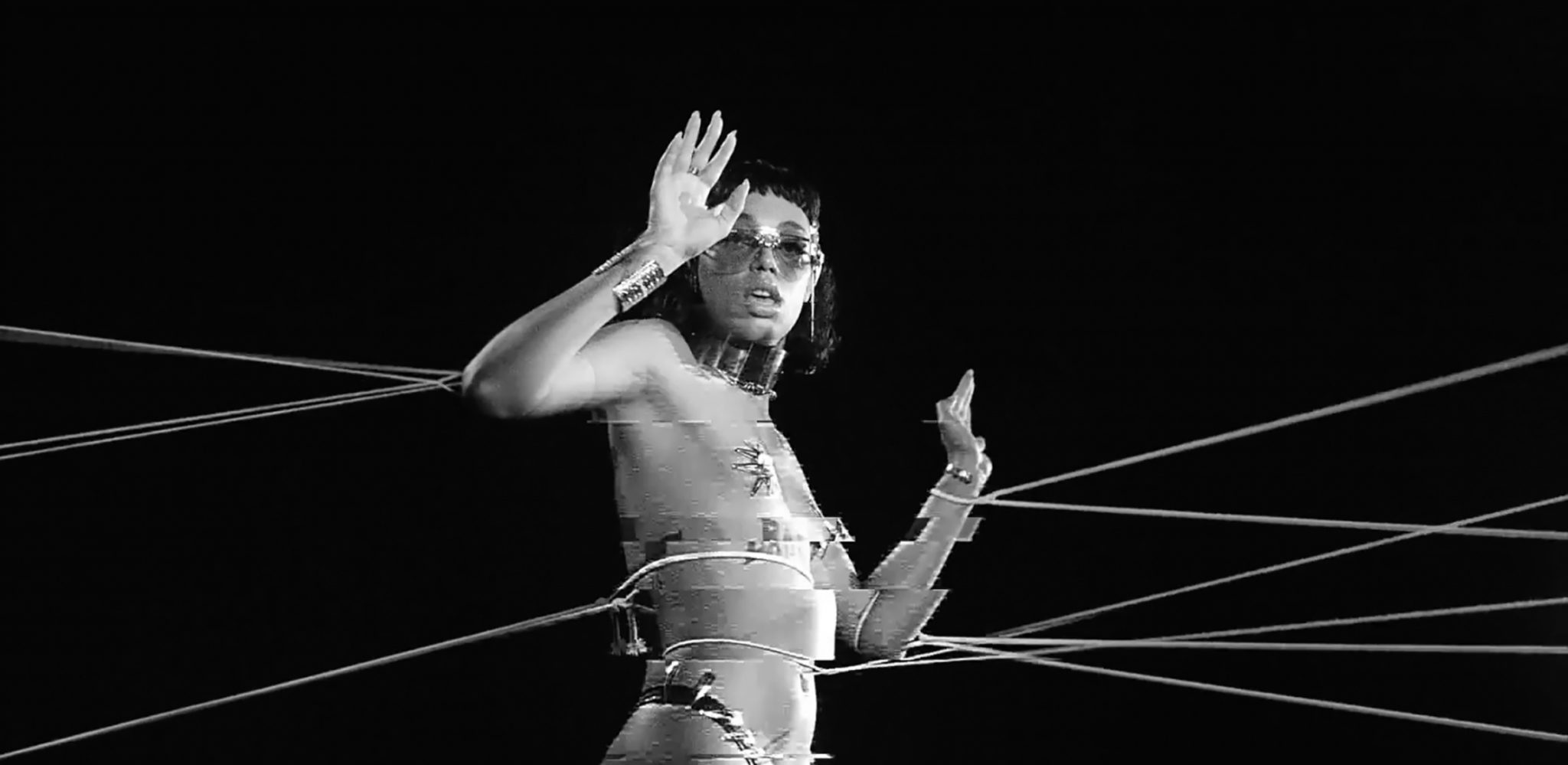

Ode’s essay too contains a subtle criticism of the instrumentalisation of Black trans identity as a ‘cause’ in the Global North, her video ending with clips of trans celebrities appearing on Oprah and trans models walking for major fashion houses (it’s a virtue-signalling instrumentalisation of which the artworld, of course, is as guilty too). The strength of the show is that it pushes lived experience and lived-in bodies – trans Black Brazilian bodies – to the forefront. Within that specificity there are universal truths about the fragility and power of the skin and bones we occupy and how nothing in the self is immutable. In Omen (2020) by Aun Helden, the artist decays and distorts her body with the use of makeup and prosthetics, the camera trailing slowly over her transforming skin and limbs to a thunderous and abstractly electronic soundtrack. While she is narrating her own subjecthood, there are wider lessons there about any kind of radical body-transformation, whether through age or disability. Likewise Urias’s Racha (2020), a show highlight for me, is a furious music video in which we first see the artist behind the wheel of a high-performance sports car. As the track proceeds the correlation between the sheen of Urias’s PVC outfit and the highly-polished metalwork of the vehicle becomes apparent. “What scares you is the power of my car” she sings at one point, as three trans dancers gyrate behind her. The implication that she is not talking about the petrol guzzler is clear.

The concept of body-as-machine builds on early work by cis-gender artists such as Matthew Barney (rebooted to a world of advanced surgery and AI) and the body-as-a-place-of-violence-and-renewal finds its history in twentieth-century feminist practices by the likes of Orlan and Marina Abramović and Brazilian Lygia Pape’s neo-concretist proposal to ‘live the body’. Yet while those older artists were bringing their bodies into the transformative sphere of art temporarily or with a specific ideological purpose, the artists in this show, all born in the late 1980s or 1990s, have no choice, as Ode writes, but to “incorporate the condition of being their own capital”, weaponising their bodies for radical, and rapid, political and social change.

Notes on Travecacceleration is at LUX, London, and online through 30 June