On Justin Bieber’s Justice and the lessons of millennial masculinity

What do you think of when you hear the name Justin Bieber? A flippy-haired tween heartthrob? A self-destructive, tattooed train-wreck with a police record? A devout Christian and young husband?

My money’s on one of the former rather than the latter, despite all three being true.

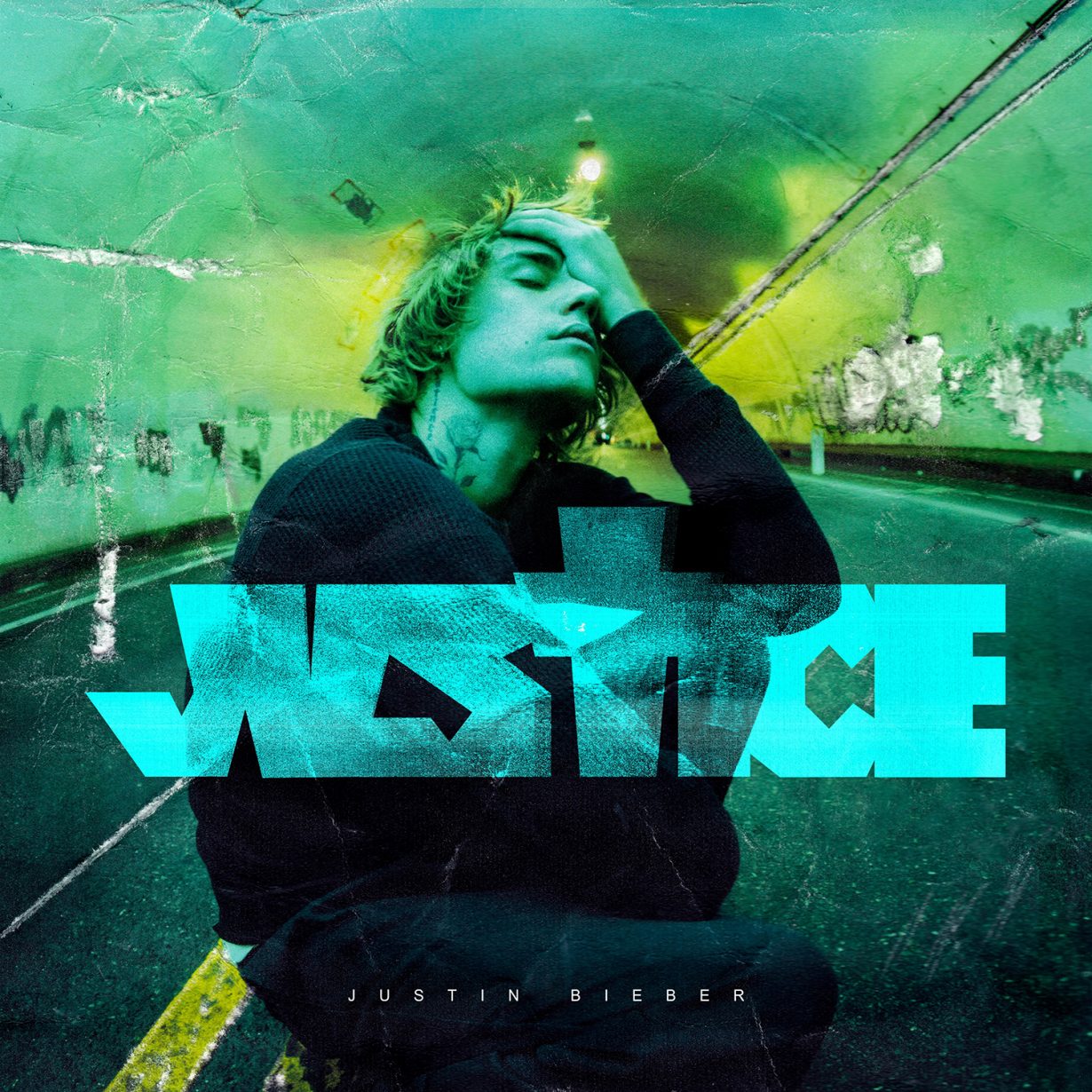

A few weeks ago, Justin Bieber released his sixth studio-album, Justice, and if someone had tried to convince me there was any substance to it, I wouldn’t have believed them. While I’ve been a fan of his for years, he’s not an artist I’ve ever taken seriously, his music falling into the category of ‘what I listen to when I pretend I’m going to give this running thing a try again’. I do not identify as a ‘Belieber’. But several listens in, I found myself frantically messaging friends in different time zones, asking if they’d listened to it, carefully selecting tracks designed to get each person through the door, wanting, needing someone to hear what I was hearing. The album was just as confusing to me as he is.

Justice is filled with love songs, uncountable God references, and two too many clips of Martin Luther King Jr speaking.

His uses of the late radical’s speech in the opening track ‘2 Much’ and the not-so-subtly titled ‘MLK Interlude’ that fractures the album reek of virtue signaling and empty gestures (topped in my book only by David Guetta’s tribute to George Floyd last May). Bieber says that he wants to ‘make music that will provide comfort; to make songs that people can relate to, and connect to, so they feel less alone’. The suggestion that loneliness and isolation are consequences, symptoms of injustice, is a message that gets overshadowed by the bungled injection of King’s words. Bieber released a band aid, mislabeled as a vaccine, branded with buzzwords, ‘green packaging’ and the promise of not just a future, but a bright one.

Which is a shame. Because as far as band aids go, this one’s got some promise. The love songs found throughout the album play with genderless, desexualized language, leaning heavily on ideas of hope, commitment and faith. In his voice, ‘Somebody’ challenges traditional notions of masculinity with an 80s-inspired power-pop background, a flawed but earnest articulation of vulnerability and public expressions of emotion. ‘Love You Different’ featuring BEAM comes in strong with dance-hall vigour in an innocent-enough promise to support his partner – the lyrics come with serious middle-school crush vibes.

But it’s not all feel-good, family-friendly fun. Listening to ‘Lonely’, a confessional ballad in which Bieber talks about his substance abuse and lack of support while sick in the spotlight, I couldn’t help but think about the spectacle of destruction and disregard for celebrity wellbeing. While a far cry from our cultural failures when it comes to hypersexualized stars like Britney Spears, for the first time it felt possible to place Bieber in conversation with larger issues about representation, image, and the commodification of public figures in the realm of creative production.

Justice touches on a wide range of themes through slickly-produced pop songs, drawing on a diversity of styles and influences that include Phil Collins, Gotye and gospel music. While merely skimming the surface, I found myself asking whether the album indicated a shift towards a more mature path forward for the musician – a question with which I was relieved to discover Pitchfork’s critic was also puzzling over. But within my own so circles, I found mixed responses, primarily from straight white men, who, while typically musically open minded, responded to questions of whether they had listened to Justice with, “No, I’m an adult male.” That’s a verbatim quote.

At the end of the day, much of Bieber’s messaging on Justice reminds me of a subsect of the cis-white-male experience – wanting to be a part of the conversation and not necessarily having the tools to do so. Having certain tools, but bigger ambitions, and not understanding or figuring out how to do the work. Who Justin Bieber was – heartthrob and trainwreck – gets in the way of his ability to reach those who might actually benefit from hearing his message, or witnessing his attempt at being a different kind of adult male. His own expression of millennial masculinity, and how he challenges that, are met and rejected by its own kind.

Striving to be something more than who he was, it’s clear Bieber’s got a way to go, but Justice offers an indicator of potential change for him, and maybe for us. In the meantime, I just might have to give this running thing a try again.