From Netflix to a current exhibition, novelist Megan Nolan explores two new perspectives on the Andes flight disaster

More than a decade ago my friend and I were hungover, talking rubbish, exchanging hypotheticals for hours on end as only overly intimate twenty-year-olds can do, and got on to the subject of the plane crash which inspired the film Alive!. This was the Andes flight disaster, the chartered flight which careened into the mountains while carrying 45 passengers, 19 of whom were rugby players who played together in a rugby union club called Old Christians. Twelve of the passengers were killed on impact, 29 would eventually die from their injuries and the subsequent avalanche. The 16 survivors were rescued 72 days after the crash, and only after two of the boys undertook an unthinkably arduous trek into Chile that took them over ten days and dozens of kilometres. Most famously, in the intervening months while stranded on the mountain, the survivors resorted to cannibalising the bodies of their deceased friends in order to survive, a morbid fact which seized the imagination of a world already rapt with horror and admiration for the ordeal which the visibly wizened survivors had undergone.

So my friend asked, “Would you eat me? If we were stranded like that?”

“Oh yeah”, I said instantly, “No hassle”.

She was aghast.

“Well, I wouldn’t kill you to eat you, I’d only eat you if you were dead”, I told her, but she demanded to know what I would do if she had begged me not to eat her before she died.

“Easy,” I replied, “I’d promise you never to eat your body but then when you were dead I’d eat you anyway. Because you’d be dead.”

“But… the wishes of the dead are sacred!” she exclaimed. “Well, no”, I said – “not, like, legally or materially speaking”.

I enjoyed remembering this exchange as I saw the exhibition Our Bed by Irish artist Joseph Noonan-Ganley at Steam Works, a recently opened studio space and gallery in South London. Noonan-Ganley has been assembling work in various mediums including film, performance, textiles and photography around the subject matter of the Andes disaster for a number of years and this show is the culmination of several iterations of this body of work which have been shown around Ireland and the UK. The crux of his attention to the disaster is not the more famous point of interest: cannibalism. Rather, it begins with a focus on, and reimagining of, textiles and debris from the aeroplane fuselage which the survivors adapted and repurposed to create structures to help them hold on. Specifically, the creation of a kind of wide sleeping bag which could facilitate the extreme proximity which was needed to endure the sub-zero temperatures.

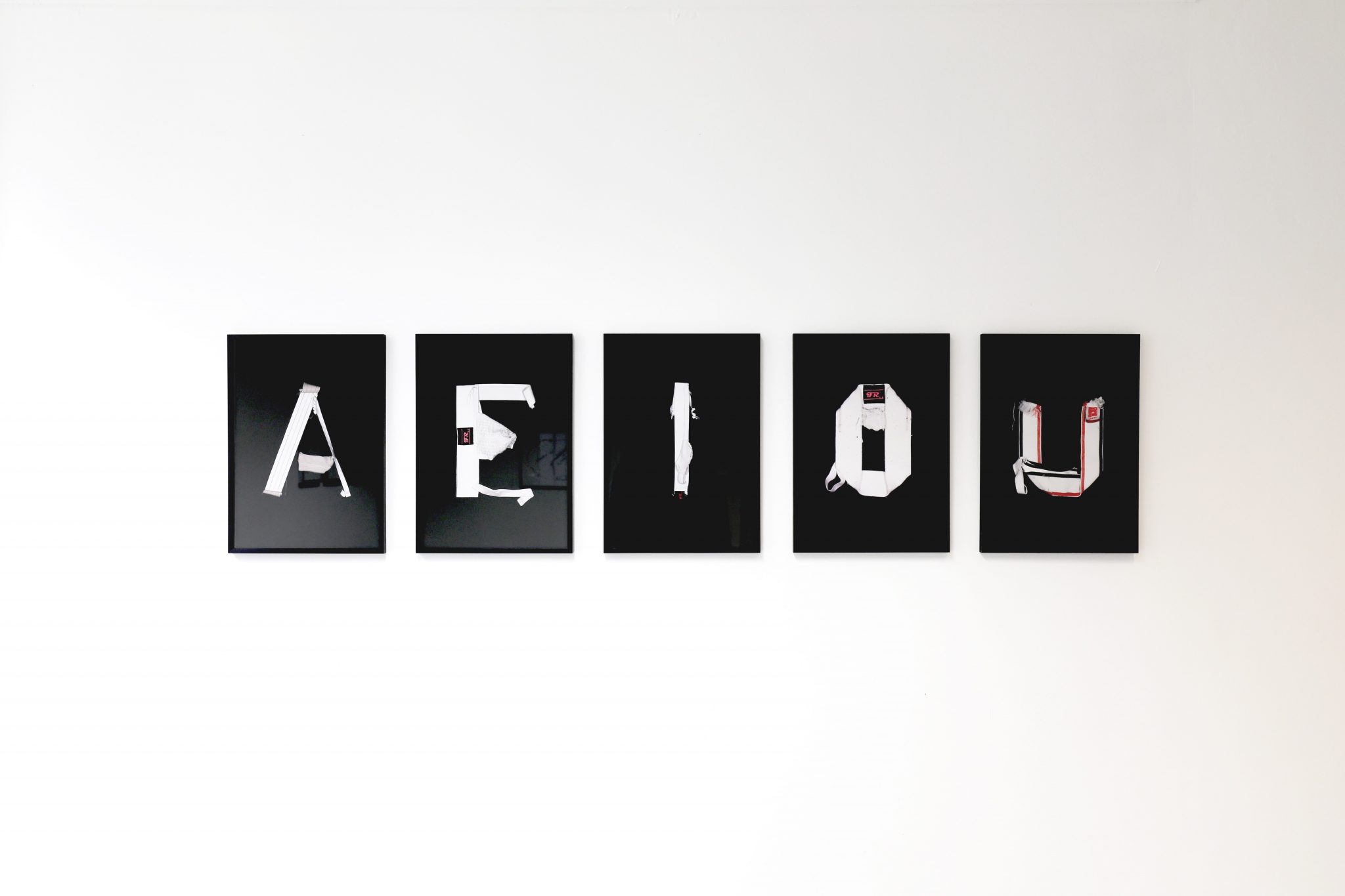

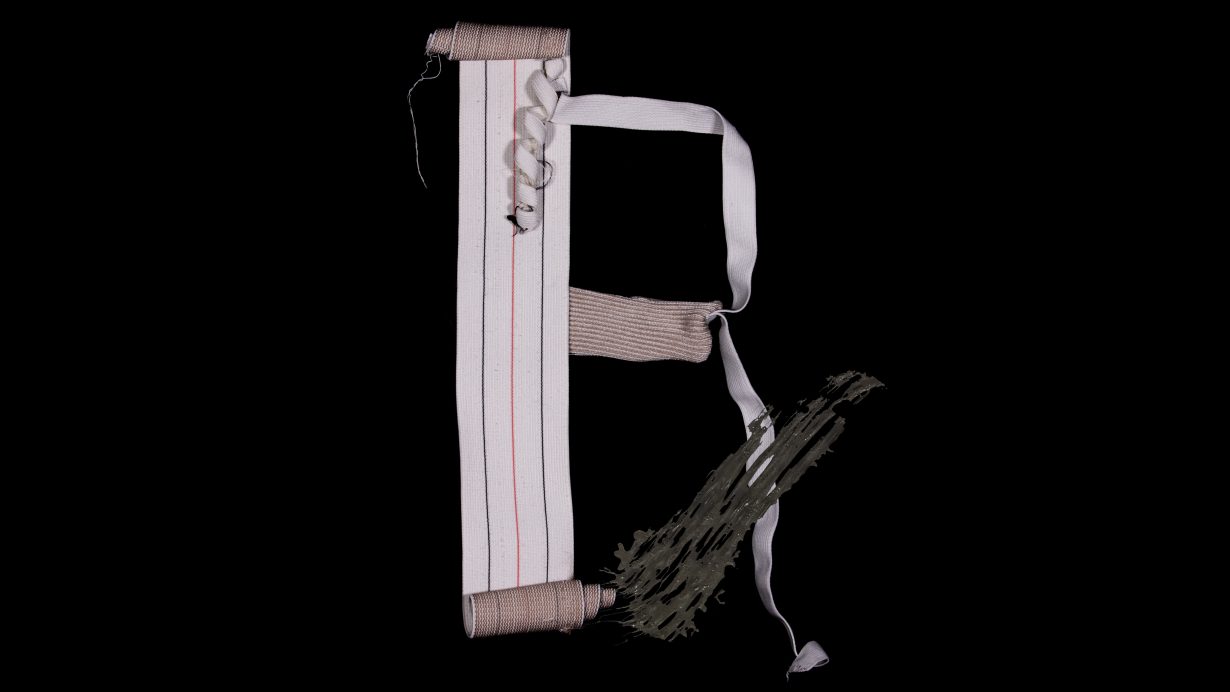

This innovation was both remarkable for its cleverness and radical ingenuity, but also moving in its expression of a dogged survival instinct which can appear to the despairing audience at home both inspiring and alienating. On the gallery’s walls are facsimiles of diagrams survivors drew to illustrate how they created bunk beds using wire from the wreckage in order to separate the sickest amongst them and create new textures of cohabitation. There are the reproductions of actual artefacts from the incident, including a photograph of some survivors before they were rescued, reclining against the plane swaddled in layers and gamely smiling, a human ribcage picked clean of meat on the ground beside them. Then there are images of an alphabet created by Noonan-Ganley using jock straps to form the roughly hewn letters. This alphabet acts as a kind of extrapolation on the fertile productivity the survivors conjured together; a new alphabet, new language, formed from the remnants of boyhood and athleticism.

These letters also punctuate the video Our Bed (2023). Fragments of survivor accounts are spoken as the jockstrap alphabet flashes. At first it seems we are listening exclusively to direct translation of the factual survivor testimony, and as things proceed the reality or otherwise of the account begins to warp and become questionable. Footage of actual rugby matches becomes distorted and saturated so that the squelches of mud begin to stain the screen, rendering the familiar green passivity of sports on in the background something exhilarating and nauseating. A pile of writhing athlete bodies entirely slick with mud cavort together. This image radiates the combination of threat, beauty and co-dependence that came to define nature itself for the Andes survivors.

By coincidence, on 4 January, a major new Netflix adaptation of the story of the Andes disaster, a feature film named Society of the Snow premiered. It joins the 1993 film Alive!, based on the brilliant book of the same name by Piers Paul Read published in 1974 and from which the testimonial in Noonan-Ganley’s video is taken. Watching both, I was struck by how the popular imagining of the negotiations between survivors about the act of cannibalism diverges in seemingly minor but actually completely essential ways. Most imagine the decision as one fraught with division and tension, and the involvement of the will of one, more powerful (alive) party being imposed upon that of the helpless and dominated (dead) party. In fact – although of course it was a repellent struggle to cross the taboo of consuming human flesh, and although some took longer to come round than others – all survivors respected each other’s perspectives and instincts, even when they held different ones.

Dying men offered up their future corpses. One man asked that his mother and sister’s bodies be spared if it was possible but assured the group that if it was necessary they could indeed go even to that place. The transgression was also in some ways sanctified, as if by necessity for cognitive and moral coherence; they were a religious group and some began to speak of the consuming of flesh as a kind of transubstantiation. There was no exertion of violence over another to survive, only intimate cooperation. In this way, too, intimacy itself is not a sentimental proposition but one more way in which life naturally gravitates towards its own continuance; the intimacy between the boys is indeed at times beautiful to witness and hear recounted, but it was also an unthinking action. They did not need to feel love or desire to blow warm breath on one another, to press body as tightly as possible to body. They knew, as we so often forget in ordinary life, that our lives are inherently porous projects, and that perseverance and ongoingness require the merged threads of connectivity instead of their severance.

The enlivening oddness of this is what most thrilled me about Our Bed, the coagulation of the catastrophically unusual and the totally prosaic. Survivors painstakingly stitched together wire and sweatshirts to have something to sleep and dream within, and several years after their rescue millions of readers around the world read about their ordeal from within their own comfortable beds. I was lying in my own as I read about the boys crafting socks for themselves using the removed flesh from the feet and ankles of the dead. It was impossible not to rub my own softly encased feet together and squirm with empathy and something not unlike guilty pleasure. Speaking with Noonan-Ganley at his show, he told me about imagining the bed as a site of time travel, a place from which we can access other people and times in unique ways. His imagining of a queer dimension to the incident – the survivors of which were, as far as we know, straight – is another imaginative proposition enabled by the actual intimacy of the true events.

In this story, intimacy is not pretty, which does not make it any less miraculous. It acts as a kind of functional, necessary foundation which can provide a starting point for any number of potentialities; the flesh passing from one friend to another enriching him with protein which allowed him to live and eventually go on to have children who would never have existed otherwise; one man going hungry so that another may feast, becoming strong enough to rescue them all; the rotating cast of three boys who switched positions through the freezing night so that each might live to touch their girlfriends at home again one day.

Megan Nolan is a novelist and columnist