An exhibition at M+ puts the region’s aesthetic identity – from woodcuts to agitprop – firmly in the picture of a tumultuous period

Starting during the late nineteenth century, Hong Kong, then under British rule, emerged as a centre of revolutionary ideas, thanks to a certain ease of travel in and out of the colony, and the mental openness of a commercial city. Chinese intellectuals trying to overthrow the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) were able to come to Hong Kong and – as long as they were not too vociferous – hold meetings, form societies, print periodicals and raise funds, creating connections that linked southern China to Southeast Asia, Japan, Europe and the United States. Before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the border was porous, and while Hong Kong and Guangdong were separate jurisdictions, they had a common language (Cantonese) and similar culture. This was a time that saw the waning of China’s centuries-old imperial system, colonial encroachment on its lands, the brutality of the Japanese invasion and the tragedy of civil war. Hong Kong, already a colony, was partially sheltered from some of this, but this peripheral appendix played an oversize role in the unfolding of events.

The survey exhibition Canton Modern shows how pivotal the region’s role was. The paintings, photographs, propaganda posters and images produced either as advertisement or for social and political satire (a medium that became popular from the turn of the century), and cartoons on locally printed and distributed periodicals displayed at this exhibition often seem to oscillate between a desire to break the norms to bring about open innovation, and a devotion to a more classical approach. Painting in a realist style, as the reformist Kang Youwei said in 1921, was a tool to ‘compensate for our country’s shortcomings’. Colonial Hong Kong, with its open doors and multiple influences, became ideal to get acquainted with Western and Japanese ideas on modern aesthetics, allowing artists and imagemakers to advertise modernity through innovative takes on classical techniques and tropes, and through groundbreaking artistic production.

In Guangzhou, commercial images were so prominent as to start new artistic trends, represented by a selection from before the Second World War, from Current Affairs Pictorial (1905–13) and volumes of manhua comics, together with commercial posters advertising Tiger Balm and other industrial products from the 1920s and 30s. Given how important commercial images were (and are) in influencing our imagination, Canton Modern underlines how cultural and aesthetic change was also effected by journalists and publishers, photographers and printmakers.

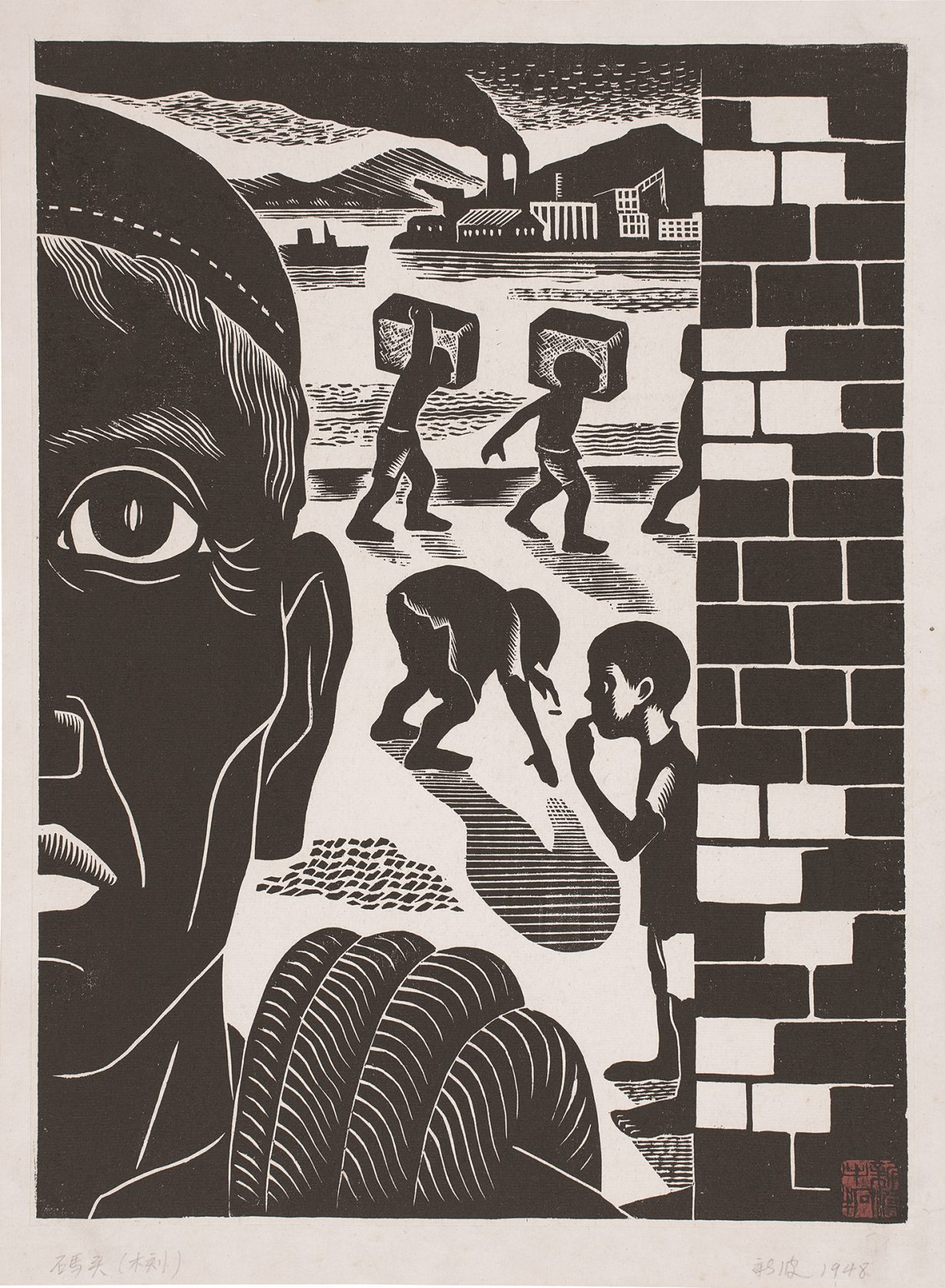

Woodblock printing became a crucial medium for artists wishing to play a role in the ongoing civil and political strife, and influence events. A photograph of Lu Xun, the revered modernist writer and founder of the New Woodcut Movement, sitting with young woodcut artists (many of them Guangzhou-based) at the Second National Traveling Woodcut Exhibition, in Shanghai in 1936, is displayed next to striking woodcut prints with themes of poverty, hunger, war and the toil of manual labour. In the section ‘Image and Reality’, Gu Yuan’s Exploding Bunkers (1948), a coloured woodcut print in black, red and white, shows soldiers sabotaging enemy positions at night, while his Seed-sowing (1939) presents the muscular back of a farmer wearing only rolled-up trousers, the darkness of his body echoing the hardship of days spent on the field. War was no longer depicted through oblique symbolism or stylised warriors: images became more immediate, and painful. Gao Jianfu’s ink painting Flying in the Rain (1932), from a distance, could seem an idyllic southern Chinese landscape, with mountains fading in the misty distance, a pagoda emerging from pine trees and a meandering river in the foreground. On closer look, though, a formation of warplanes in the sky testifies to the Japanese military invasion and the harshness of contemporary reality. Chao Shao-an’s ink Skull in a Faded Dream (1955) portrays an abandoned skull and bones, among forlorn blossoms in a grey landscape.

Li Hua cut his woodblocks with great economy of lines, showing the suffering of the poor in Famine (1934) and Praying for Rain (1934). The propagandistic aspect of these prints foretells what these artists would eventually turn to: Li’s Sanmenxia Dam Construction (1959), a beautiful drawing in charcoal, is also present. Gu Yuan, too, paid homage to the communist industrialisation with his Restoration of the Anshan Steel Mill (1949) – a Japanese steel mill in China’s northeast damaged during the Second World War, dismantled by the Soviet Army and restored in the socialist era. These works are in the section ‘Parallel Worlds’, which portrays how Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland were by now separated by a much-harder-to-pass border, even if a conspicuous number of the socially engaged artists who had been active in Hong Kong went north to paint for the People’s Republic of China and its ideals, with works glorifying Mao Zedong.

A section on ‘Identity and Gender’ shows social renewal through the role of women, both as artists and as subjects: from the first studies of nudes to appear (including a rather intriguing set of portraits of Buddhist nuns in the nude from Guangzhou’s Tandu’an Convent, by Tan Yuese, a Buddhist nun), to images of women dressed in fashionable, modern clothes, like the elegant lady in Moon Above Willow Sprigs (1941) by Szeto Kei.

After Hong Kong’s marginality turned out to be quite pivotal for revolution to take place, the two locales were pulled politically apart, and reunited: the exhibition concludes with images of the first direct trains since the founding of the People’s Republic of China connecting the then-colony to China. This is an exceptional show: few of the artists presented here are familiar to the non-specialist observer, and the narrative frame in which these 80 years of visual production are explored is compelling. It doesn’t shy away from politically charged images in a post-National Security Law Hong Kong that has learned to fret about such things, and sheds light on a tumultuous period in China, putting the role of Hong Kong firmly in the picture.

Canton Modern: Art and Visual Culture, 1900s–1970s at M+, Hong Kong, 28 June – 5 October

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next: What will the Northern Metropolis mean for Hong Kong’s future?