A first translation of her 1969 Self-Portrait sees the writer and feminist activist dissect the role of the critic

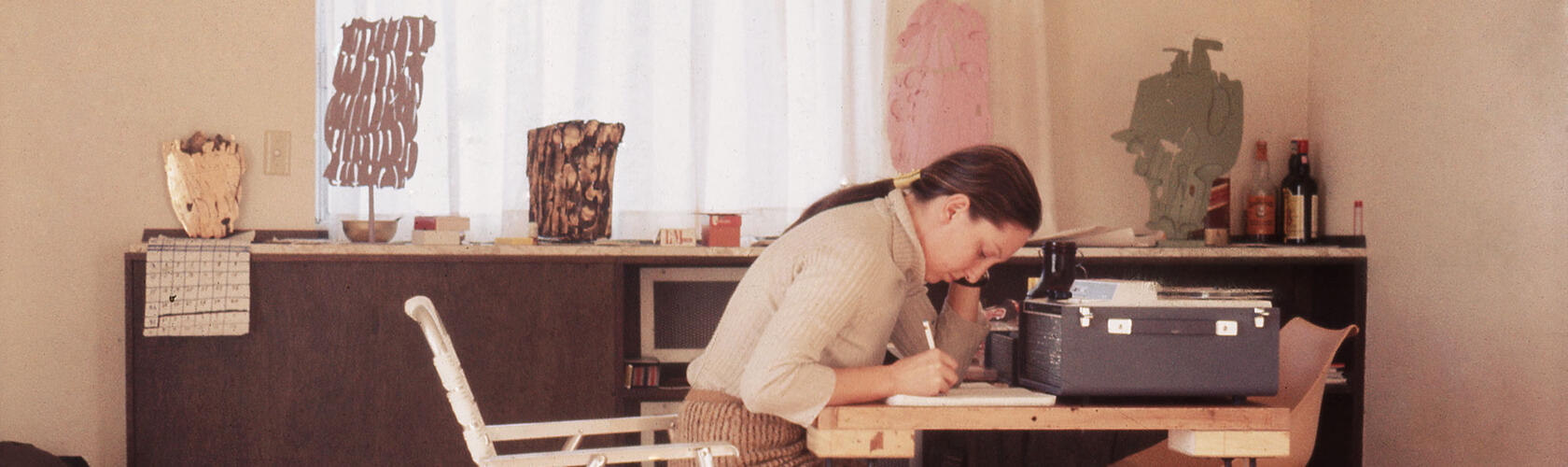

What is art criticism? Does anyone really care? Criticism is about creating discussion and fostering community; at least that’s what critics and those invested in criticism like to tell themselves. But after around ten years of working as an art critic, Carla Lonzi started to feel the opposite: that the role of the critic involved a ‘codified alienation towards the artistic fact’, that criticism was an accomplice to a class system, corralling art into a rarefied sphere in which creativity and life are seen as separate things. Self-Portrait – originally published in 1969 and translated here for the first time – is the Italian writer’s extended dissection of and farewell to criticism. Her only subsequent writing about art occurred in her diary; energy was instead poured into activism and feminist writings, and cofounding the influential collective Rivolta Femminile.

The premise of Self-Portrait is simple enough: to cut together a disparate set of interviews with 14 artists into a new, longer, meandering conversation. The result is at first deeply disorienting, as if you’ve dropped into a room where everyone is talking past each other – only one of the interviewees, Carla Accardi, is a woman; the rest are men who seem more than happy to pontificate. Drawn from interviews recorded between 1965 and 1969, the book is a handy portrait of a time: artists like Jannis Kounellis and Lucio Fontana speak at length about their approach to artmaking while offering all manner of asides – talking about nature, unions or hippies, or Fontana insisting that his concept of Spatialism was much more important than Pop. At times the book is insightful, at others turgid, but that’s the point. All the formatting and cleaning up of artist statements was what stripped criticism of its potential. Here the half-baked thoughts and dead ends that form part of most interviews but are usually edited out for the sake of ‘clarity’ are the focus. Art comes closer to life.

While some of the language used by Lonzi’s interviewees is dated, peppered with casual racism and misogyny and offhand art-historical generalisations, the art system described and the stratifications embedded within it are, depressingly, much the same as today’s. And the critic still performs an unresolved role, pinging between amplifier, translator or obfuscator. Lonzi’s tussle with criticism is useful in the sense that it helps shed light on what has become a perpetual ‘crisis’ of criticism. This isn’t because contemporary criticism is limp, or fading, or ignored; ultimately it’s critics themselves who are always on the point of breaking. Criticism is a personal crisis. Sometimes it doesn’t work; usually it’s too many thoughts jammed into too few words that can only ever cover the tip of the iceberg. Or as Lonzi puts it, the critic ‘trespasses onto things that humanity has toiled at much more and much more deeply, and says his piece and then he returns to his smallminded things’.

Self-Portrait has been likened to Lee Lozano’s Dropout Piece (begun c. 1970), but it’s worth also recognising it as part of a line of literary goodbyes to art criticism, alongside books like Amy Fung’s Before I Was a Critic I Was a Human Being (2019) – which comes to many of the same conclusions – and William J. Gass’s 2015 essay ‘A Body of Work’, written as he left criticism for the work of nursing. But no one else has exited so comprehensively or so stylishly as Lonzi. Self-Portrait is as personal as it is meandering, unresolved and open. More importantly it offers potential for the critic as both editor and conduit – shaping a mode of writing that mirrors the multivalence of an artwork, teetering wildly on the precipice between insight and invisibility, complicity and collapse. This, Lonzi suggests, is where criticism, and the critic, are found.

Self-Portrait, by Carla Lonzi, translated by Allison Grimaldi Donahue, published by Divided Publishing