As the Freedom-of-Information requests displayed by the artist at A. Squire evidence, there are so many creative ways of saying no

In Franz Kafka’s 1915 short story Before the Law, a man approaches a gatekeeper and asks to enter, only to be told he cannot. Might I be allowed to come in later on? asks the man. ‘It is possible,’ says the gatekeeper, ‘but not now.’ Years pass and still his requests are politely deferred. Finally he dies at the gate, an old man. Kafka’s inscrutable bouncer came to mind as I read the Freedom of Information (FOI) reply letters, sent to hundreds of real, anonymised individuals from 17 British ministries and governmental departments between 1 October 2023 and 29 October 2024, displayed in Ceidra Moon Murphy’s Public Interest. One thing unites these otherwise disparate citizen requests for information (on everything from arms exports to Israel to the RAF’s involvement in 2018’s Mission Impossible 6), which Murphy acquired by sending multiple FOI requests of her own: the state’s response, invariably, is no.

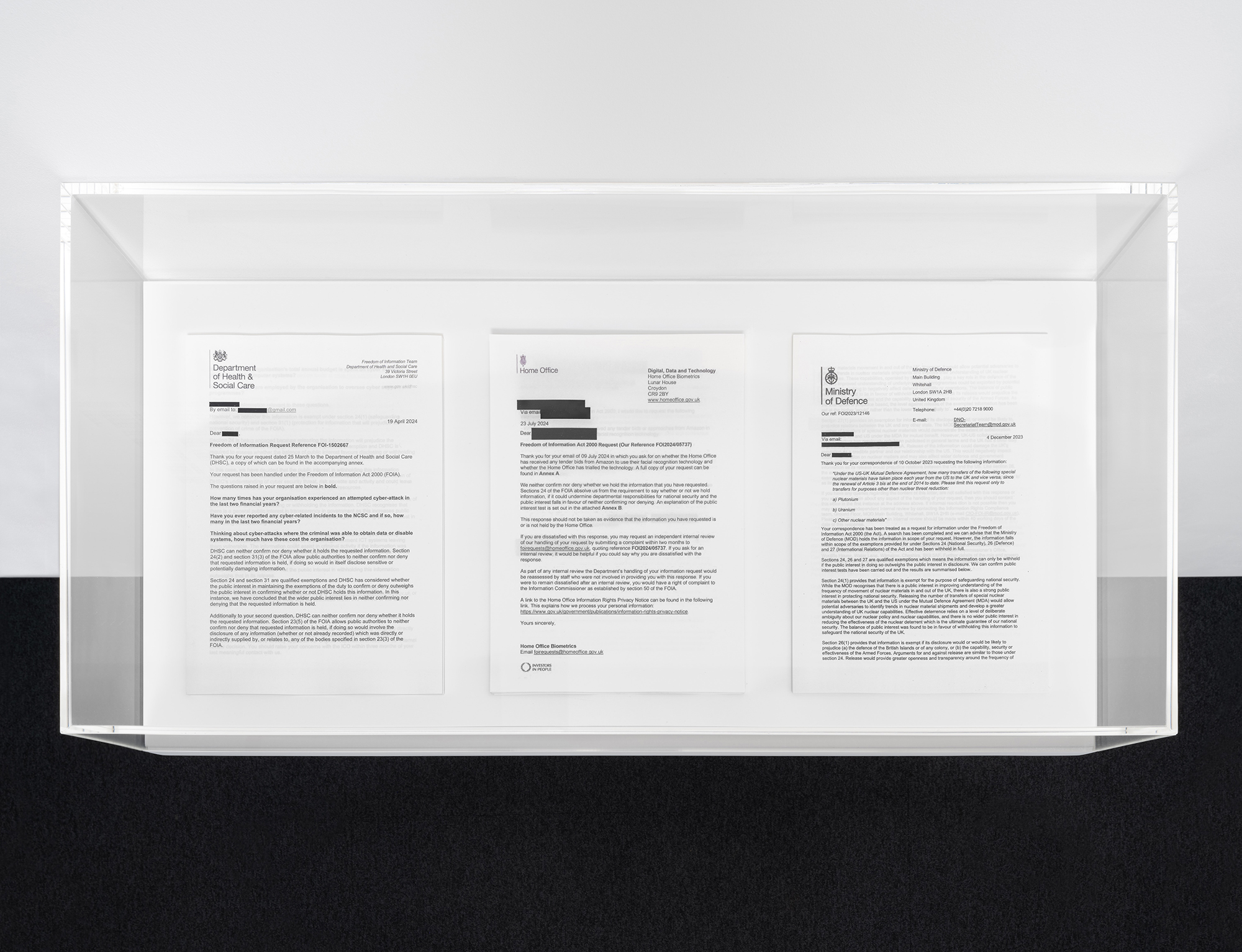

But there are so many creative ways of saying no. The UK’s FOI act (which since 2000 has given the public the right to access information held by public bodies) has 16 exemptions. These are printed in a diminutive sans-serif list on the otherwise blank walls of the gallery, while the A4 letters are in piles sorted by which exemption has been applied, sealed neatly inside wall-mounted Perspex display cases. Only the top letter of each pile can be viewed. This spartan exhibition is notable precisely for how little it chooses to reveal, dealing in a demure opacity that embodies the game of show-and-tell played by a government capable of finding seemingly infinite ways to wriggle out of their own commitment to transparency. ‘I can confirm that the department holds information within the scope of your request’, states a typical sentence, coyly. After you encounter a few of these deflections, the experience of reading each new letter becomes increasingly anticipatory as you wait for the inevitable courteous ‘no’ to arrive. ‘After careful consideration…’, the gatekeeper begins once again, and you already know how this ends.

Just one of the letters on display is addressed to Murphy herself. Her application to see all the official responses to unsuccessful FOI requests was denied ‘because it is considered vexatious’ and ‘appears to be frivolous in nature’. In a recent interview published by A. Squire, the artist (who was born in 1998) speculated over the use of language aimed at her in this instance, which ‘reading as a young woman, seemed gendered’. It would be tempting to interpret it like this, considering the teasing courtship of control evident throughout the letters, with the state invariably the patriarch, but I read it differently. Murphy’s exhibition appears to continue a long tradition of institutional critique, from Hans Haacke to Andrea Fraser. The accusation of frivolity cuts through Public Interest like a garish stripe. What’s being sold seems to be a deliberately facetious exercise in wasting time – her own time, the government’s time and, lastly, her viewer’s. Is her successful acquisition from the state of hundreds of other unsuccessful FOI requests, with the intention of showing these in a gallery, really in the public interest? In leaving this ultimately self-reflexive question open, Murphy tilts the metaphorical mirror at herself as artist until she captures the absurdity not only of the law but of the artworld’s political limits, too.

Public Interest at A. Squire, London, through 22 February

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.