With the country again confronting tyranny, Filipino artists are responding with urgency and fury

On 5 May, the Philippines’ National Telecommunications Commission ordered ABS-CBN off the air. Amid the global COVID-19 pandemic millions of Filipinos were left without access to the vital information broadcasts on television and radio from the country’s largest media conglomerate. (ABS-CBN web platforms were not covered by the order, and at the time of writing are still operating.) The shock of the channel’s closure prompted Filipino artists – both young and those who lived through Ferdinand Marcos’s military dictatorship – to accuse Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s government of censorship and exploiting the health crisis for political gain. Artist and chairman of Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) Leonilo ‘Neil’ Doloricon publicly stated that the manoeuvre, the most recent in an ongoing confrontation between Duterte and ABS-CBN, goes beyond the threat to press freedom: ‘It also poses a serious threat to the independence of cultural institutions, including the mass media, where artists and cultural workers are supposed to enjoy creative expression free of state intimidation. What this shows is that the Duterte regime is not only dead set at controlling the flow of information but also culture and the arts.’ Indeed, echoes of historic artistic suppression are reverberating within the community, triggering national trauma from the violence and oppression of the Marcos era.

This is the second time the network has been forced off the air, the first being in 1972 when Marcos declared martial law. His first Letter of Instruction, issued that September, directed officials to requisition privately owned newspapers, magazines, radio stations, television facilities and all other news media – effectively imposing blanket censorship in an attempt to prevent the dissemination of antigovernment views. The Marcos-allied media company Kanlaon Broadcasting Systems occupied and broadcast from ABS-CBN facilities until its reclamation during the 1986 People Power Revolution. As the realities of martial law settled over the country in 1972, the visual arts community initially went quiet, with many of its members fearing for their lives. A few arts-activist groups began to form by the late 1970s and explore forms of artistic resilience. Kaisahan (Solidarity), a group of social-realists that had banded together in 1976, was committed to putting up political resistance and forging a national identity while also depicting the true conditions of society and democratising art. By the early 1980s, organisations opposing the dictatorship, such as the CAP (formed in 1983), began to surge and mobilise campaigns against the government. In 1986, the peaceful protest of the People Power Revolution finally overthrew the Marcos regime.

The COVID-19 quarantine began in Manila on 15 March and was subsequently expanded to the rest of the country, with some of the toughest restrictions in Asia. In addition to implementing WHO-mandated social-distancing guidelines, Duterte closed all airports in Luzon (the Philippines’ largest island), established checkpoints at entrances to Manila, halted public transportation and imposed an 8pm–5am curfew. He dubbed this measure ‘Enhanced Community Quarantine’, which was largely viewed by the public as a necessary action. But when ABS-CBN was silenced, critics viewed the action as personal rather than civic: Duterte’s animosity towards the network can be traced to the 2016 presidential election, during which ABS-CBN refused to air his ad campaigns; after his election to office, the network maintained critical coverage of his deadly war on drugs. Last December the president warned the broadcaster, “Your franchise will end next year. If you expect it to be renewed, I’m sorry. I will see to it that you’re out.”

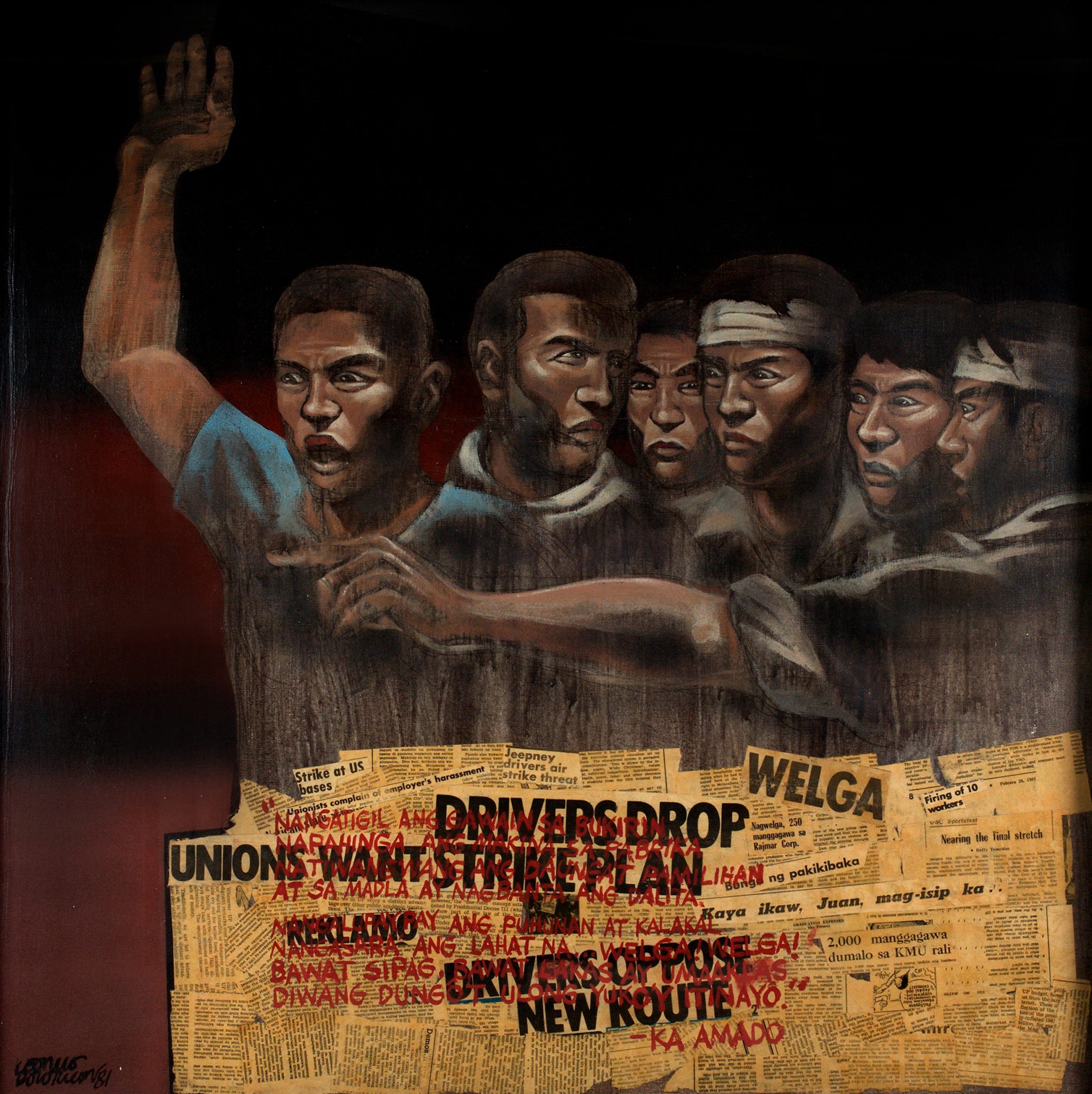

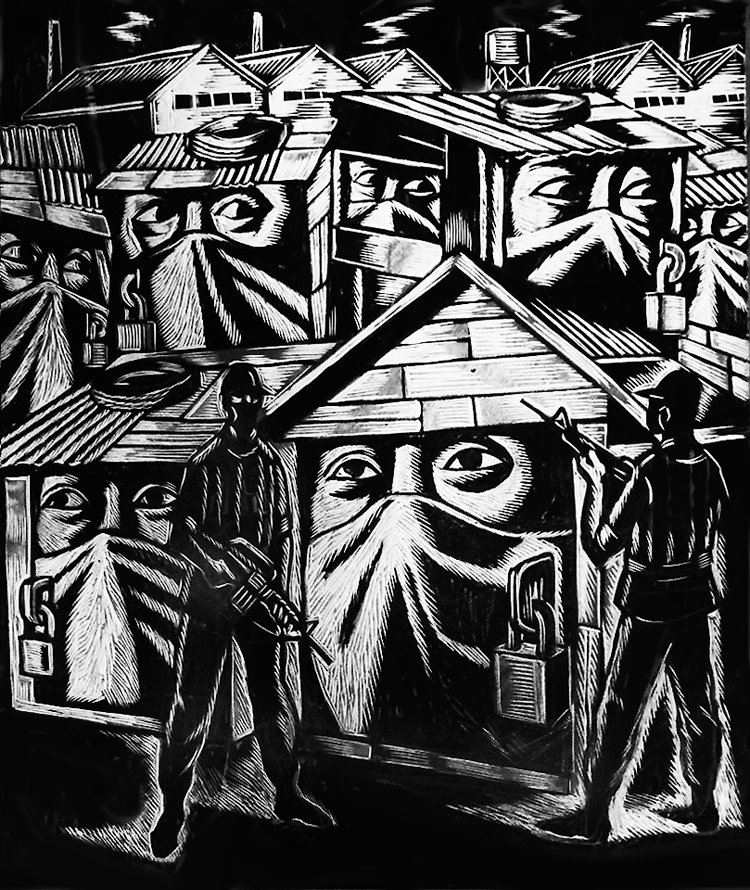

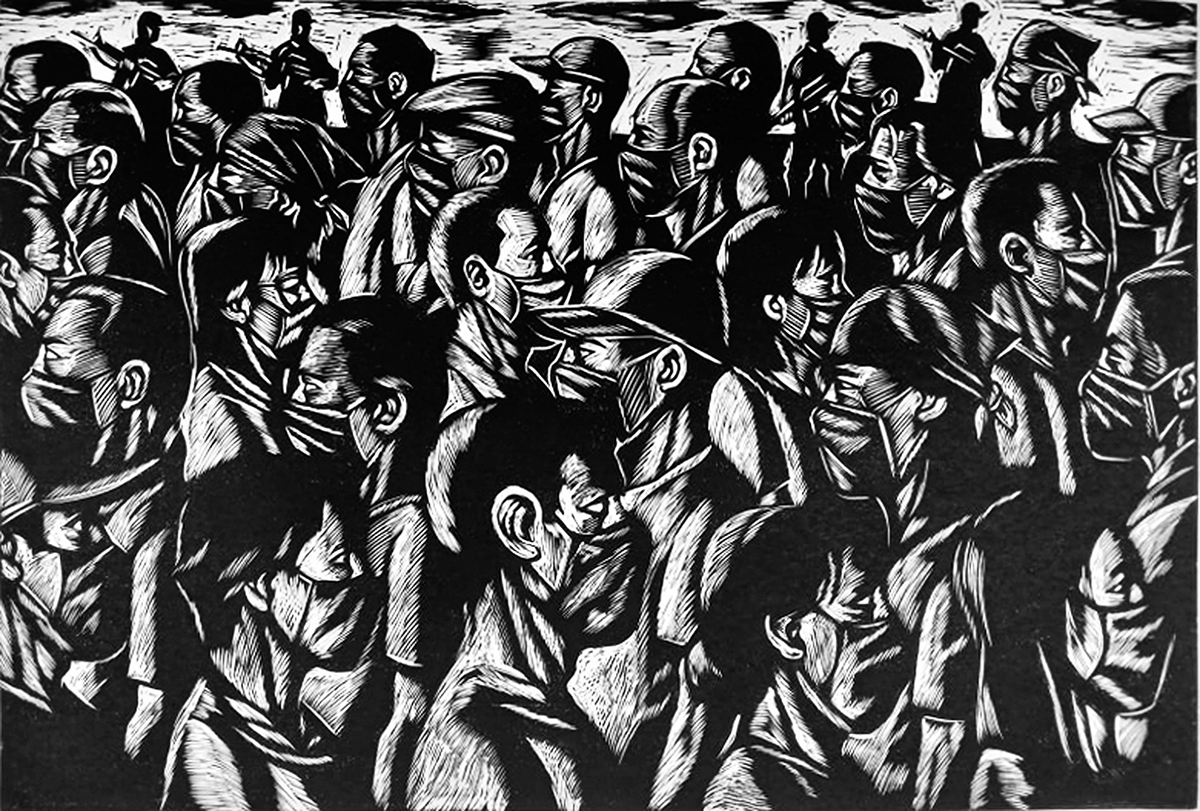

During the pandemic, Neil Doloricon, who in addition to his work with CAP is a founding member of Kaisahan, has continuously posted new prints and digital cartoons to his Facebook page. Though the means by which he exhibits his practice have changed over the past 45 years, there are significant consistencies in the work itself, which, along with the artist’s other activities, are worth examining in the light of this new era of governmental overreach. On 6 April Doloricon posted Pila (Queue), a linocut print that harkens back to his social-realist roots. Five rows of individual men and women are crammed into the image, with each section of the queue facing a different side of the frame. Four ominous figures stand in the background, holding machine guns and surveying the scene before them. Each civilian has donned the mandatory facemask, yet they are so tightly packed that their bodies nearly touch – too close to abide by social-distancing guidelines. Figural repetition is a motif of Doloricon’s oeuvre – in his 1981 painting Welga (Strike), featuring a typically social-realist aesthetic, six male jeepney drivers are huddled over a newsprint collage filled with headlines about strike action, over which the artist has boldly painted, in blood-red, a Tagalog text by writer and labour leader Amado V. Hernandez that repeats the word ‘Welga’ twice. The leftmost member of the group raises his right fist to claim the viewer’s attention, while the rightmost member, his head bandaged, stretches his arm out across his companions to point an accusatory finger at something off-canvas. The only one among the group who looks out to acknowledge the viewer seems to be standing behind the others, little more than a head gazing unsettlingly from between other bodies. What is clear from comparing these artworks is that Doloricon has retained a visual style. The angular features of Welga’s figures are present in the artist’s latest group of prints. Such aesthetic consistency demonstrates his desire to uphold the original intentions of the social realists: to reflect the present conditions of the country and unify the populace. And yet, where Welga exudes rebellious fervour, Pila appears Kafkaesque – an incredulous reaction to the Philippines’ current reality.

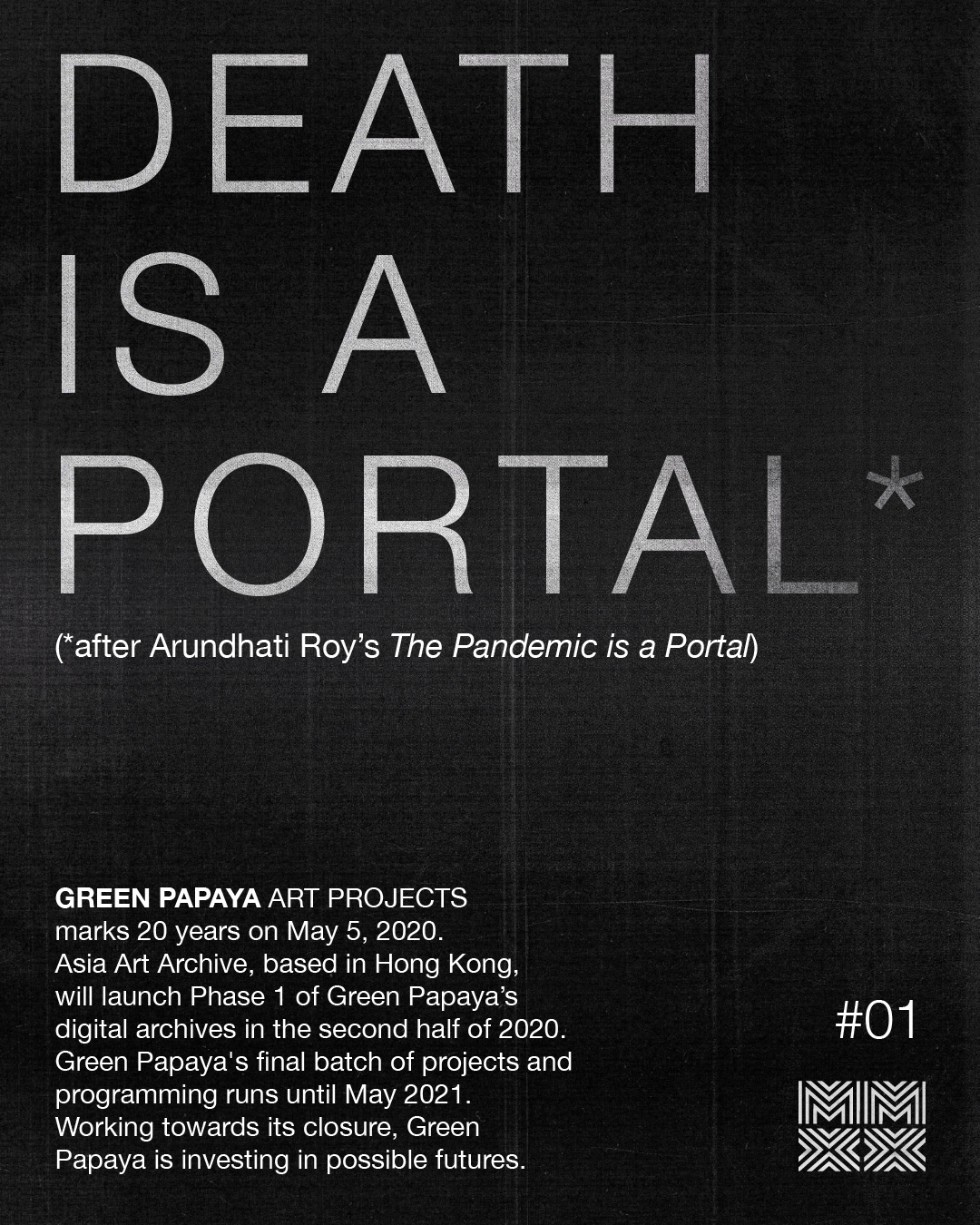

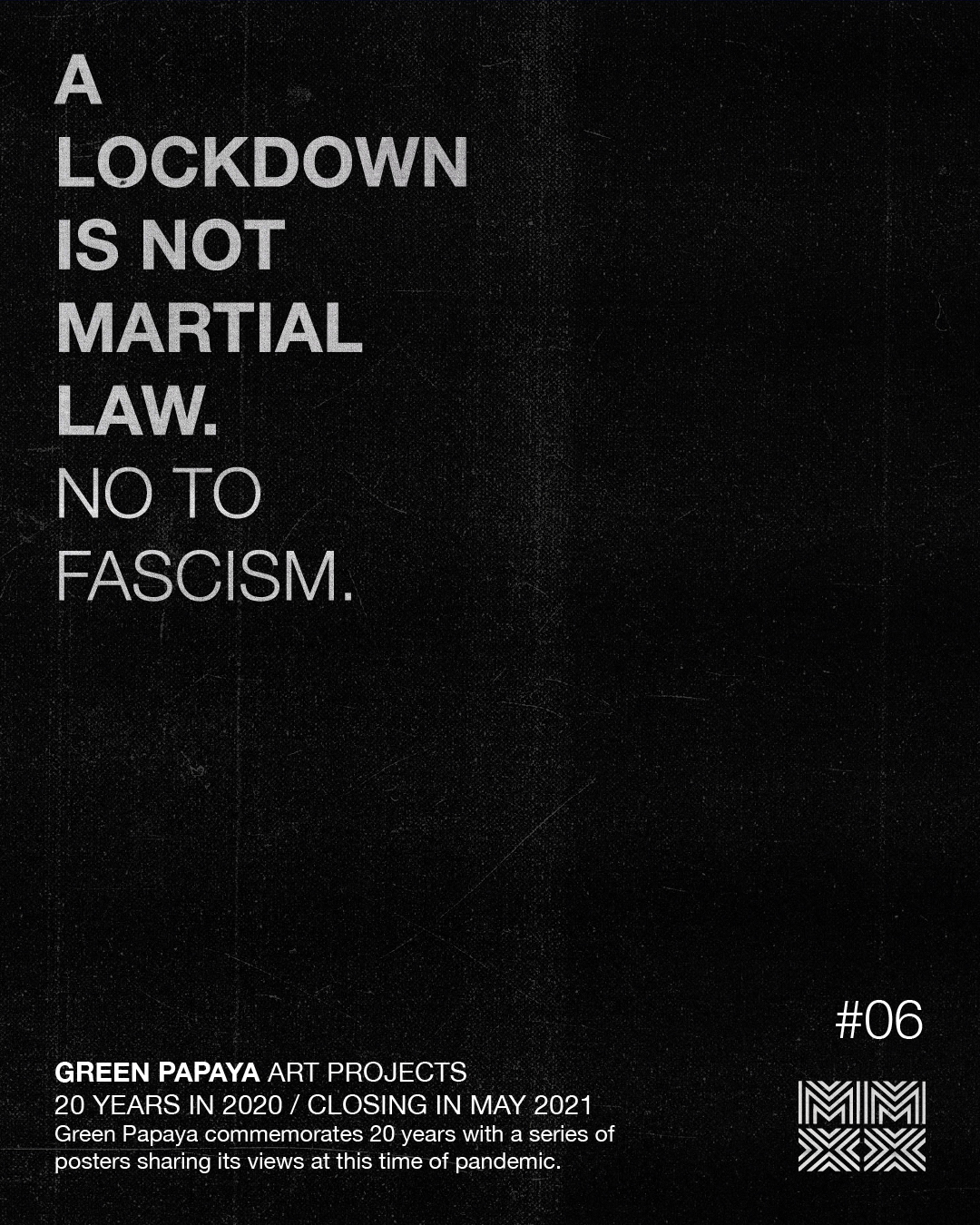

Meanwhile, Green Papaya Art Projects, an art collective and Manila’s oldest artist-run space, is commemorating its 20th anniversary with a series of 20 black-and-white posters that reflect upon the Philippines’ response to the pandemic, among them one that reads, ‘A LOCKDOWN IS NOT MARTIAL LAW. NO TO FASCISM’. Norberto ‘Peewee’ Roldan, cofounder of Green Papaya, is notably the former creative director of ABS-CBN (1994–98; 2002–07). The posters are created digitally, printed, then uploaded and shared via Facebook and Instagram. Each mechanical lag made by the printer is visible in the skips on the black-ink background, endowing them with a temporal specificity. When quarantine restrictions are lifted, Green Papaya intends to print a billboard-format zine and produce a limited edition of the posters. The first reads ‘DEATH IS A PORTAL’, based on Arundhati Roy’s recent essay ‘The Pandemic Is a Portal’, in which Roy reflects on the Indian government’s response to the pandemic – emphasising how the health crisis has revealed both the country’s social inequalities and an opportunity for reform. Green Papaya’s modified declaration, ‘death is a portal’, goes beyond the indexical suggestions of pandemic to its undeniable consequence – death. On one hand, the axiom refers to the casualties claimed by the disease; on the other, it marks the augmented number of deaths from the Philippines’ militant conduct and lack of preparedness.

The actual number of COVID-19-related fatalities in the archipelago is presently undetermined, but over 30,000 Philippine citizens have been arrested for violating lockdown restrictions. On the day of ABS-CBN’s broadcast cessation, Green Papaya shared another poster: ‘SHUTTING DOWN A MAJOR BROADCASTING NETWORK DURING A PANDEMIC IS MADNESS. IT IS A DISSERVICE TO THE FILIPINO’. While many of the posters take poetic tones, this one exudes urgency and fury. During the 1970s, after martial law was first imposed, visual ephemera such as protest graffiti, wall periodicals and sticker-posters were disseminated discreetly, as Jose Maria Sison, founding chairman of the Communist Party of the Philippines, recalls in his 2015 essay ‘Revolutionary Literature and Art in the Philippines: From the 1960s to the Present’. However, as this oppression continued into the 80s, rage swelled against the government and protest visuals erupted into mass movements. A 1985 poster-work by the artist Anna Fer, Oppose State Terrorism, was created towards the end of Marcos’s reign, as the public seethed in response to his demand for a snap election. Here, around a central image of flames, Fer depicts scenes of violence against civilians. With the country again confronting tyranny, Green Papaya’s posters acknowledge past visuals of dissent but forgo imagery, taking instead a simple and stark graphic approach that suggests a primary urgency to respond to current events and invigorate the viewer against injustice.

The primary aim with Doloricon’s and Green Papaya’s quarantine works seems to be widespread digital distribution, given that – for many – social media has become the sole means of news and communication beyond one’s immediate surroundings. Artists can find a haven and permanence here (though with this permanence comes the risk of unwanted government attention; see below). As it happens, an accidental fire ripped through Green Papaya on 3 June, magnifying an obvious purpose for social media as a digital record. (The collective was in the midst of digitising its extensive catalogue of ephemera for Hong Kong’s Asia Art Archive, following the Manila-based organisation’s decision to close its doors in 2021.) Green Papaya shared the devastating news on its Facebook page, opening with an update on the Philippines’ current crisis and including an apology to all the artists who had entrusted their materials to the archive. ‘We are safe for now,’ the post ends. ‘But the house is still burning.’ The double entendre haunts the reader, ensuring the artistic community’s brief sigh of relief while still bracing for further disaster.

At the time of writing, the Philippine government is in the midst of approving an antiterrorism bill that grants the government extensive powers to detain suspected terrorists without arrest warrants. Critics have denounced the bill as another move to silence dissent, infringing the 1987 Constitution’s Article III, which protects free speech that largely manifests today online in a country ranked the heaviest internet users in the world (97 percent of Filipinos online have a Facebook account, according to Bloomberg). Already prior to the bill’s passing, private citizens, among them a salesman, a teacher and a writer, have been arrested as a result of their social-media posts. When news broke the government was expediting the anti-terrorism bill, activists found ways around the internet’s authorial risk – augmented by the tyranny of martial censorship – through the use of VPNs and fake email addresses. But these acts of digital guerrilla warfare have been met with an unsettling response: thousands of fake Facebook accounts stealing the names of journalists and students to send threatening messages. Though social media has been the primary means of communication and protest during the pandemic, many commentators have pointed to the internet as essential to Duterte’s presidential election victory, whose campaign organized groups according to geographic zone (including one for overseas workers) to distribute daily campaign messages and propaganda presented as news on real and inauthentic accounts across social media.

The internet has always been an ideological battleground, but the closure of ABS-CBN and passing of the anti-terrorism bill elevate the stakes in a country where the additional threat of government intervention looms over that posed by the pandemic. Still, within these respective artmakers’ bodies of quarantine works are the prevailing sense of solidarity and nationalism – ideologies that have previously facilitated the country’s historic liberation from oppressive powers. In Doloricon’s Pila, civilians outnumber the armed authorities, just as Green Papaya’s posters plainly take the side of the Filipino people against various adversarial forces. While confronting the challenges at hand, these artists maintain glimmers of hope for their country. The final poster in Green Papaya’s pandemic series once again quotes Roy: ‘IT IS A PORTAL, A GATEWAY BETWEEN ONE WORLD AND THE NEXT. WE CAN CHOOSE TO WALK THROUGH IT…’