A new survey of the country’s Qing dynasty from 1762 to 1912 sets out to celebrate its diverse artistic treasures but ultimately fails to escape the colonial gaze

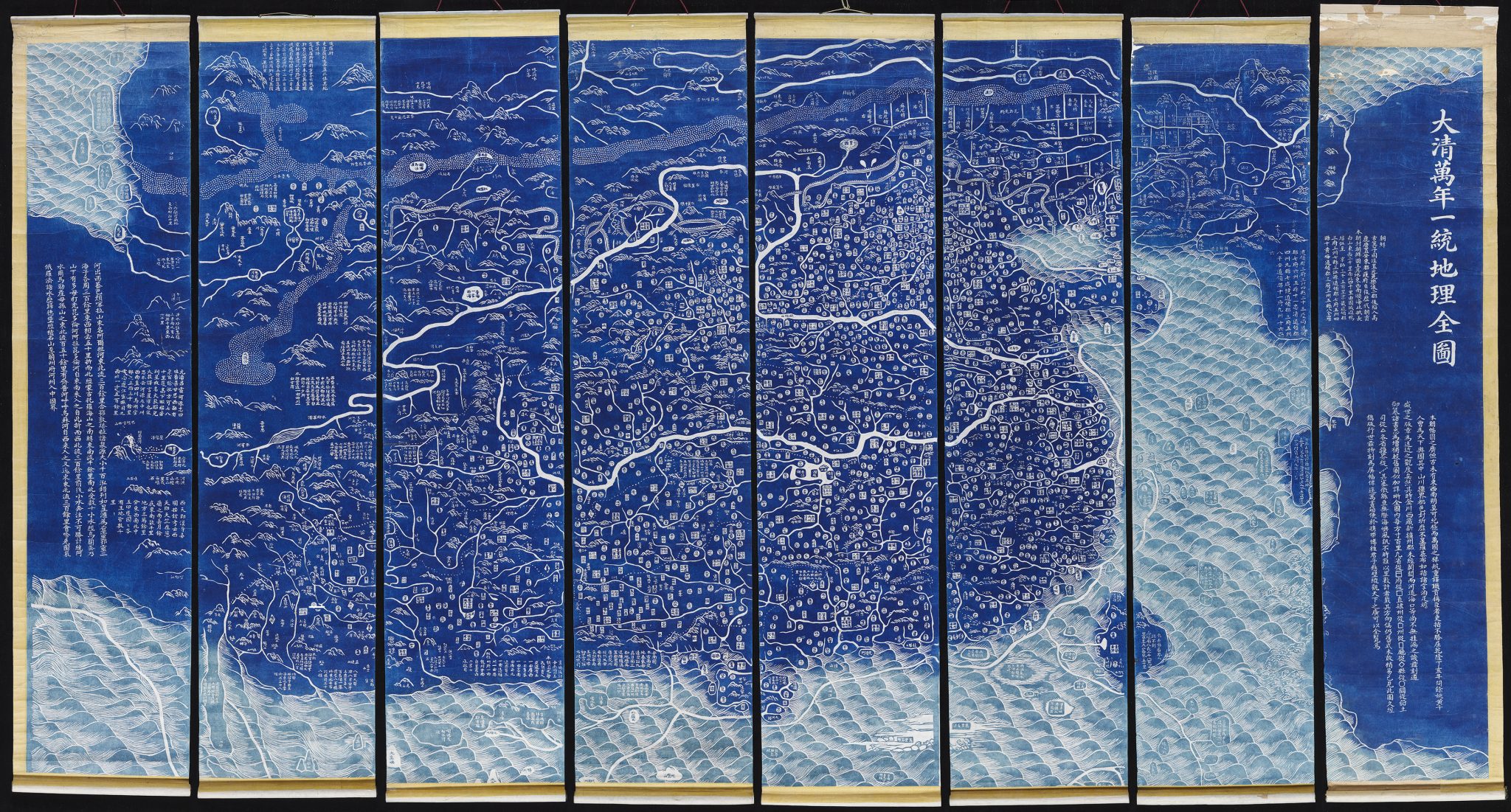

This expansive exhibition begins with the ‘All-under-heaven complete map of the everlasting unified Qing empire’. At 2.3m wide, the map, an 1800 copy of a 1767 original rendered in monochromatic blue hues, depicts the expanse of Eurasia, from Korea to England and from Russia to a misplaced Indonesian archipelago, all of it viewed from a southerly, aerial perspective. This last makes it feel as if we (or the Qing emperor himself) were hovering, godlike, above what is currently the South China Sea. And perhaps the emperor did have more-than-his-usual reasons to feel godlike: the 1759 conquest of the Dzungar Mongols allowed the Qing to claim Xinjiang as its territory. The map speaks of the Qing’s sense of identity, pride and ownership, as well as its ambitions and apprehensions. Closer along the eastern coastline, topographic details, administrative divisions, province borders and the Great Wall are painstakingly delineated. Yet such cartographic precision frays into unspecified deserts and mythological mountains as the map approaches its distant, mysterious western frontiers, where the vast regions of Central Asia and Europe, as well as the Atlantic and the Indian oceans, all conflate into one small area. More than anything the map poses the territory as an abstract graph, ready to be occupied by the empire’s geopolitical imaginations and desires – all of which would be shattered during the coming century, when a combination of state corruption, military defeats, imperialism and ethnic unrest would render them to dust.

The Qing was in decline; people suffered – that is what normative histories say about this period in China. This show challenges that: focused less on the gloom, it highlights the signs of resilience in culture, which found creative ways of adaptation and regeneration at times of crisis. For this was also a century of new ideas, including new forms of publication – illustrated newspapers such as Dianshizhai Pictorial visualised urban gossip, civic affairs and European technological spectacles; an early-nineteenth-century fascination with taking rubbings of ancient structures became the cornerstone of China’s evidence-based archaeology. We see the emergence of a fully fledged Peking opera; new designs of toys, street advertisements and new year’s prints. Throughout the exhibition, in which court life and warfare are only two of six cultural themes (the others being artistic circles, vernacular life, cross-cultural encounters and the revolution), you learn that the state and the army do not determine all of China’s nineteenth-century experience. The ways people lived their lives were far more diverse.

A luxurious folding screen made of kingfisher feathers; a hyperrealistic portrait made through Suzhou embroidery after a studio photograph; miniaturised furniture for tomb decor; and Chinese-styled ecclesiastical textiles offer a quite exotic visual pleasure even to a Chinese eye – even in China these are rare. In glass cabinets in which peculiar-looking objects like these accumulate, there is an uncanny reminder of the kind of displays that began to dominate middle-class Victorian homes and British curiosity stores, where such foreign treasures became markers of cosmopolitan taste as well as signals of Britain’s global presence. Here that kind of post-export afterlife is hidden. With the result that you end up feeling that the visual satisfaction on offer here is not so different from the type enjoyed by a nineteenth-century Westerner, who gazed at the Orient to find peculiar designs, strange customs and exotic pleasures.

Equally unaddressed are the problems of collecting itself and the roles played by collectors, soldiers, British imperial officers – all of whom present as ‘donors’ in the labels that accompany the objects on show here. Victor Sassoon, for example, whose vast collection of Chinese ivory was donated to the British Museum in 2018 via The Sir Victor Sassoon Chinese Ivories Trust, developed his wealth through the Sassoon family’s opium trade and once owned over 1,800 properties in Shanghai. The British Museum’s labels and website, however, mention nothing about who Victor Sassoon was (or that his descendant James Sassoon is deputy chair of the museum’s board of trustees). The kingfisher-feathered folding screen was purchased by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum after it mysteriously ended up in Paris’s 1867 International Exposition, in which the Qing themselves did not participate. The label states that, at the time, ‘a committee of French businessmen, scholars and soldiers selected Qing artefacts’ and organised a display ‘reflecting Chinese culture’, as if the objects at the exposition are a celebration of global friendship, when nineteenth-century world’s fairs were known to have celebrated colonial triumphs and white supremacy, and when the attempt to ‘reflect Chinese culture’ came just six years after the Qing’s Imperial Summer Palace was looted by Franco-British soldiers. This bad habit of unclear or evasive provenance research is echoed by the exhibition’s recent scandal, when poet and translator Yilin Wang found that her translation of a poem by nineteenth-century proto-feminist Qiu Jin was printed on a gallery wall without due acknowledgment.

Resilience and precarious living have been hot concepts in recent years (as we see through the continuing impact of Anna Tsing’s 2015 book, The Mushroom at the End of the World), but the endeavour here looks unintentionally ironic. Elsewhere the British Museum is displaying numerous objects, such as a sculpted Rapa Nui (Easter Island) head and ancient Buddhist śarīra, dislocated and decontextualised, that are more dead than resiliently clinging to life.

China’s Hidden Century at British Museum, London, through 8 October