Lehmann’s works, of fissured tissue and fragmented forms, capture the tension between our human bodies and something more elevated

In a new series of eight small, deft paintings on linen, canvas and panel, Claire Lehmann merges the visual language of late-capitalist imaging with that of Early Renaissance painting. Along with the printed instructional imagery – taken from medical textbooks, industrial diagrams and other scientific and technical imaging – she has worked from for decades, here Lehmann burrows into early experiments in 3D imaging technology. Perhaps inevitably, these works depict failed renderings of bodily flesh. Melancholy hisses through her depictions of fissured tissue, as humans and animals appear to fragment and dissolve in mid-motion.

The largest of these paintings (at the still relatively diminutive scale of 76 × 61 cm), Leaven (2023–24), depicts a still life with a cake in the shape of a Paschal lamb. A slice of the animal’s flank is presented, as if in offering, on a plate near the edge of the table, closest to our point of view. Its ‘sacrifice’ is in tension with the spare domesticity of its surroundings: a draped cloth, Delft-style blue-and-white pottery, a carved wooden butter knife. The linear perspective signalled by the slanted chequered floor visible below the table – suggestive of the perspectival devices of fifteenth-century European paintings – allows the composition to snap visually into the logic of Renaissance-era representation, even as its religious symbolism suggests less ‘rational’ antecedents.

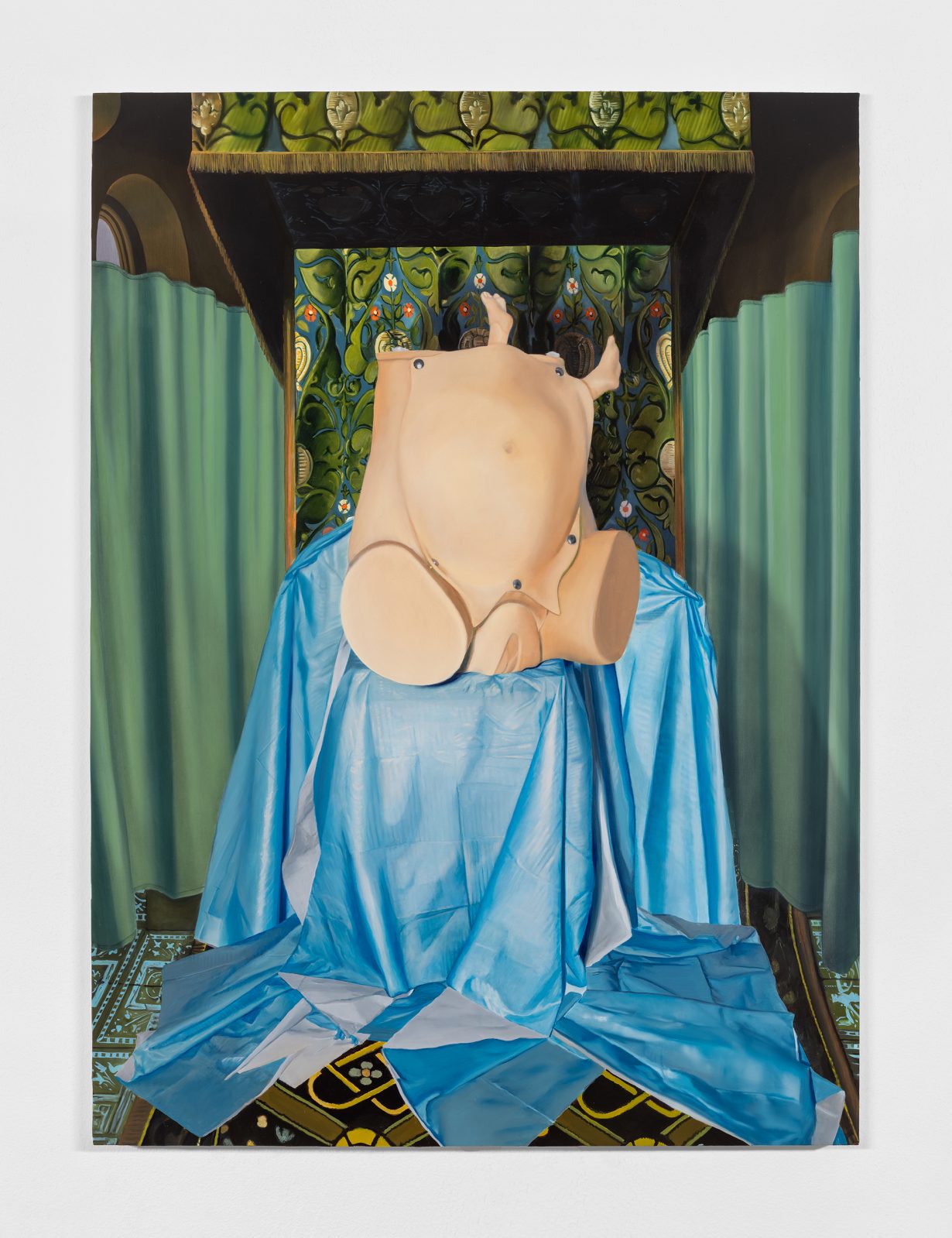

The influence of religious iconography is present as well in Lehmann’s Fontanel (2023–24), in which a composition suggesting Early Renaissance devotional portraiture of the Madonna and Child is recast, with an obstetric mannequin laid atop the Virgin’s blue robe in place of her head and trunk. The dummy in this work was directly copied from a photograph of one used to train doctors; these teaching objects are suggestively termed ‘phantoms’ within the medical establishment. Above the mannequin, a pair of upturned tiny legs sprouts, as if they have cracked through the titular ‘fontanel’ (the soft place in an infant’s not-yet-fused skull) of this torso-cum-head. Lehmann has previously used images of other medical devices in her works, including ‘tissue-equivalent phantoms’ used to train radiologists to detect hidden tumours, and she is attuned to the wrenching humanity of these objects and the maladies of their proxies.

Lehmann’s paintings work to bridge the tension between human flesh – soft, undulating, mottled – and the crisply rendered diagrams that instruct us in the business of how to enhance and extend our human capacities. When the latter aspect is absent in this work, we miss it, as in Perruque (2024), an abstracted matrix of hair strands loosely evocative of a wig, and Diviner (2023–24), a headless robed figure whose garments are shot through by indiscriminate rays of light. As the artist observed in an interview with Frieze in 2021, oil paintings are essentially pigment suspended in a kind of amber, and if not preserved for all eternity, they will certainly outlast other attempts to map the visual world, as these diagrams, like our own bodies, deteriorate or are phased out.

The Understudy at Bel Ami, Los Angeles, 20 April – 25 May