A more complex emotional picture emerges in the new TV adaptation of Sally Rooney’s debut novel

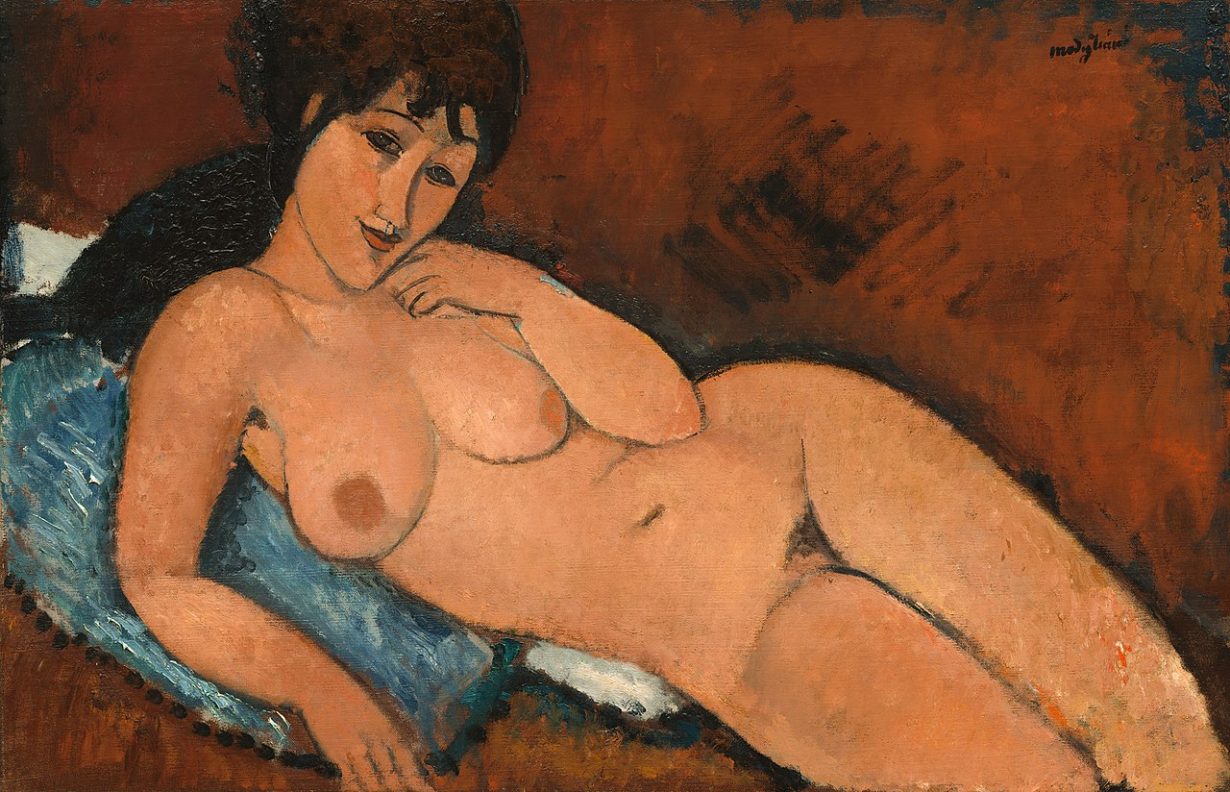

In the opening pages of Conversations with Friends (2017) – Sally Rooney’s debut novel that is so culturally notorious it hardly needs even this introduction – 21-year-old protagonist Frances spots a ‘Modigliani print hanging over the staircase’ of Nick and Melissa’s semi-detached house in the Dublin suburb of Monkstown; ‘a nude woman reclining.’ Knowing the extra-marital tangle that is to come, the prominent nude might seem to carry a hint of eroticism (of a passive and tepidly cultured kind that would, in all likelihood, appeal to Rooney’s typical readership). But, at this stage of affairs, it simply indicates to Frances a fully-realised state of adulthood she is yet to enter. ‘I thought: this is a whole house. A family could live here.’

The print is a perfect choice, and not just because both Rooney and Modigliani are connoisseurs of brunettes with unreadable expressions and elongated limbs. A Modigliani print is supposed to suggest a sophisticated, bohemian adult who enjoys long dinner parties, red wine, and cigarettes before bed. This, of course, is exactly how Melissa and Nick’s thirty-something life appears to Frances and Bobbi at the novel’s outset. Yet, a Modigliani nude is also exactly the kind of print a university student could find at a freshers’ poster fair, snuggled alongside Che Guevara and Audrey Hepburn. It evokes an educated, creative taste, in a way that is safe and blandly mainstream; similar in effect to carting a Sally Rooney tote bag around town. That Melissa and Nick display the print only signals a concern with appearances; with how they are perceived. That Frances reads it as a sign of grown-up worldliness only emphasises her own naivety.

All this is to say that what sometimes gets lost in discussions about Rooney, and the sad girl/lit girl cult that has sprung up around her, is her remarkable attention to detail – her scrutiny of surfaces. Love them or hate them, it is hard to contest that Rooney’s novels excel at exposing the contradictions between the way her characters present to the outside world, and their internal state. Look at Conversations. A single reference to Modigliani on the second page pretty much tells you all you need to know about the central cast; their self-consciousness and pretension.

In the new BBC adaptation of Conversations with Friends (2022) – written by Alice Birch and directed by Lenny Abrahamson, aka the team behind the 2020 TV adaptation of Rooney’s Normal People (2018), minus Rooney herself – the Modigliani is nowhere to be seen. Instead, Melissa and Nick’s mid-century modern home is painted in a range of artisan greys, and decorated with a range of abstract expressionist pieces. Many of the series’s ‘conversations’ with ‘friends’ play out in the kitchen, where a Cy Twombly-esque print looms over them, punctuating the greyscale like a mess of intestines on a pavement. Perhaps there was no deeper meaning to the set design than wanting the house to portray a contemporary bourgeois experience through a palette reminiscent of upmarket Airbnbs and overpriced restaurants, but the switch from a slim-limbed nude to an abstract tangle – a sudden punch of scarlet – seems to go to the heart of this adaptation. Charged gestures! Profound emotion! The raging chaos of the subconscious! Authentic experience that cannot be contained in words! All set against a muted wash, a dull facade…

Watching the way the story advances at a snail’s pace, some people will undoubtedly wish the walls could talk. Indeed, early reviews are in and the consensus seems to be that the series is a flop – that it is too slow; that Frances and Nick have no spark; that it needs livening up, a splash of intestines on the pavement. It is certainly true that for the majority of the series, Melissa and Nick’s abstract expressionist prints are where directness and immediacy of expression start and stop. Of course, stilted and flawed communication is integral to Rooney’s exposition of contradiction, but, with her dialogue largely jettisoned and without Frances’s excoriating narrative voice, often what is left is the Great Unsaid. Newcomer Alison Oliver’s performance is undeniably exquisite, but it is also undeniable that no amount of lip picking, nail biting and laden stares can convey the supposedly earth-shattering, identity-shifting emotional motion sickness Frances finds herself subject to in her turbulent relationship with Nick. However, this all being said, there are ways the series is better for it.

Five years ago when Conversations with Friends was published, I was 23, a recent English Literature graduate, and obsessed with the book in a way that only stating those two facts can begin to explain. I could add that I had recently experienced a long-drawn-out, confusing and painful process of seeking a medical diagnosis, or that I had recently dated a man who lived in Dublin, but all that really needs to be said is that I felt fiercely protective over Frances when friends of mine called her character narcissistic, selfish and annoying. Watching this adaptation, I completely understood their point.

The same viewers who will be put off by the series’ slowness and silence might see this as another epic failure on the adaptation’s part. A failure to capture the sense of relatability so many commented on when the book was published – the tenet that spawned a thousand think pieces on Millennial Fiction. Yet, without Frances’ internal back-and-forth, what we get – all we can get – is the surface. And, looking from the outside, other characters seem not only more fully-realised, but better than they do through Frances’ anxious, critical eyes. Bobbi’s care for and patience with Frances comes to the fore, as does Melissa’s generosity, vulnerability and self-negation – her willingness to try and make an arrangement between herself, Nick and Frances work, despite her own feelings of humiliation and uncertainty. Frances’ silence in the face of Melissa’s openness does not seem enigmatically conflicted, but unthinking and even cruel. The struggle between internal perception and external appearance might have lost its prominence, but a more complex emotional picture emerges in its place. Instead of a solo study – a single nude – the story is an ensemble, a tangle, a slow-moving and knotted mess.