How Netflix’s reanimators mistook the essence of the original

‘There’s a new bounty on the line… but is it worth the trouble?’ ran the tagline of the teaser for Netflix’s recent live-action remake of the ‘90s anime Cowboy Bebop. If viewing figures and critical responses are anything to go by, the answer was not in the affirmative. The cancellation of 2021’s Cowboy Bebop adaptation – after only one season – is hardly a surprise then. Yet its failure is revealing. It clarifies what made the original anime work so well. And it unveils the fundamental flaws at the heart of remake culture.

It’s easy to see why a studio might be tempted to revive such a series. Originally broadcast on Japanese television (1998-1999), Cowboy Bebop is among the most critically revered anime. It was ahead of the curve in approaching TV with cinematic ambition, and its setting, spanning the solar system, offered a vast repository of adventures. So, there’s a proven model, a built-in fanbase, and rich creative seams to mine. The retrofitted nature of Cowboy Bebop would also facilitate reinvention. Inspired by Blade Runner, the original animation collective Hajime Yatate, led by Shinichirō Watanabe, built it from the scrapyard of the past, adding an immersive sense of history, filled with intriguing anachronisms. The picaresque adventures undertaken by the crew of the Bebop spaceship were an assemblage of genres – space opera, western, kung fu, film noir…

This fragmentary approach was held together by several binding attributes. One was an incredible score by Yoko Kanno, which however it roamed was rooted in the jazz that gave the series its spirit. Another was the fractious misfit would-be family of bounty hunters aboard the Bebop. Their wisecracking jaded thrown-together feel, which both balanced and accentuated scenes of pathos, came from space trucker films like Alien (1979), and would go on to be hugely influential, most notably on Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and other films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. With such prescience, what could go wrong?

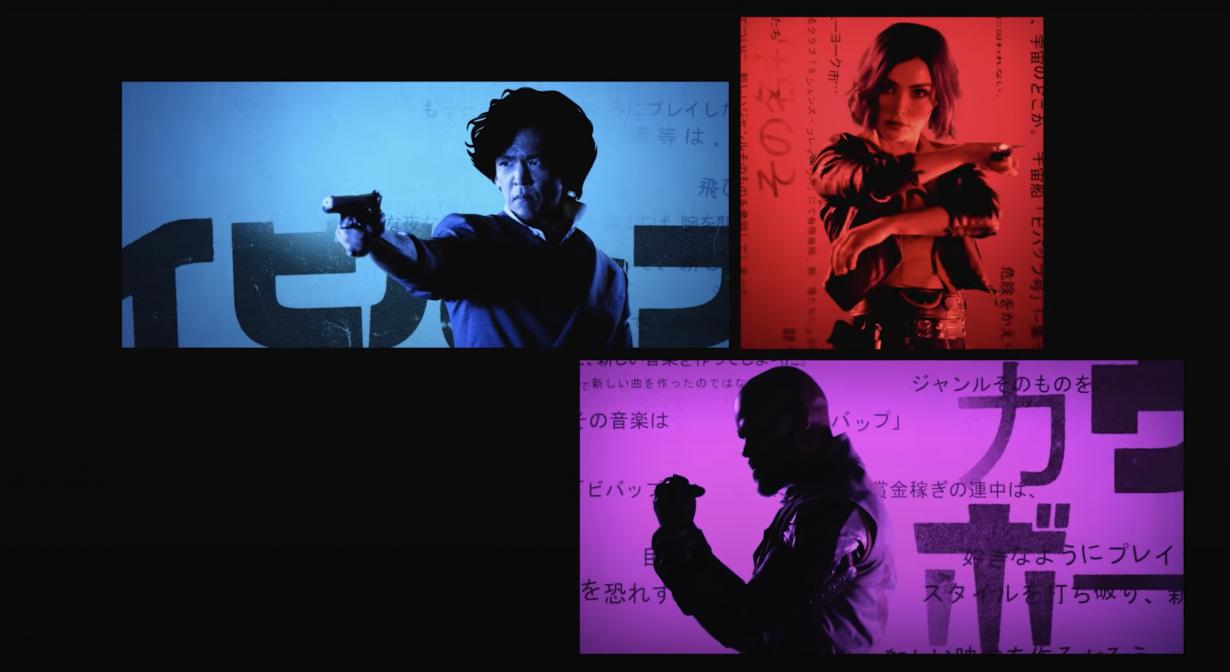

The question should have been, what could go right? Admittedly, the aesthetic of the original remained largely intact, with frequent affectionate nods to the 1998 series. It was a delight that Yoko Kanno returned to soundtrack the series. And the actors did a lot of heavy lifting, with sterling performances by John Cho (‘Spike Spiegel’), Mustafa Shakir (‘Jet Black’) and Daniella Pineda (‘Faye Valentine’). Yet the reasons for failure were there from the beginning. The writing was too far down the pecking order, with lame humour and risible dialogue alienating rather than immersing the audience. The tone was also askew, with jarring ultraviolence eroding emotional connection. The occasional scenes of quiet zen in the original were washed away by sound and fury. A sense of dynamism was inevitably lost in the translation from anime to real life, but this wouldn’t have capsized the series had they written a tale that a viewer might care about.

In a deeper sense, the Cowboy Bebop reanimators mistook the essence of the original. Take the central figure of Spike. He belongs to the future, yet he clearly derives from an earlier age. His alienation is not that of the hikikomori but rather the ennui of a dishevelled wandering flaneur. He is dressed in the immaculate effortless cool of Yūsaku Matsuda in Detective Story (1983) but equally belongs to Japan’s rich tradition of existentialism, from Ryūnosuke Akutagawa to Hiroshi Noma, Osamu Dazai to Kōbō Abe. This is mostly lacking in the remake and, when it does appear, it falls flat, weighed down by sentimentality, knowing, and kitsch.

Similarly, Cowboy Bebop 2.0 largely misses the crucial role jazz plays in the original. It’s not just that it adds propulsion and pathos, though it does so supremely; it also adds foundation. Jazz requires themes to periodically come back to, to anchor or orbit, to prevent spiralling off into space. The sheer multiplicity of influences and directions of Cowboy Bebop mean that great care must be taken to hold it all together. The group within the Bebop are the hub of the wheel, the stabilising gyroscope, the heart of a heartless universe. They are united by the fact they are broken people haunted by their pasts. Whatever eclectic backdrop they are whizzing through, Cowboy Bebop remains a noir. This essential emptiness, the show’s soul, is missing in the remake.

The problem that Cowboy Bebop’s recent failure reveals is much wider than the franchise. It’s evident that the sassy backhanded phrases and mining of pop culture that may have seemed fresh in the early days of Quentin Tarantino or even Joss Whedon are tired and formulaic now. There is a discernible mistrust and condescension towards the audience, with the iceberg effect essential to speculative worlds being thoroughly defrosted by exposition and cliché. All too often, remake culture results in, at best, passable cosplay and, at worst, uncanny valley betrayal. Its attempts at engagement are too reliant on the thin gruel of nostalgia and the cheap trick of recognition. In a way, its issue is that of the cover version: if it doesn’t transform the original, why does it exist? If it succeeds in transforming the original, why isn’t it just a new work in itself? The industry, behind Cowboy Bebop, seems all too often risk-averse and ideas-bereft, either of which is survivable but not in combination. And yet there are more creative people and options than ever.

In Buddhism, there is a state called Śūnyatā whereby, very loosely, the ego is transcended, and nothingness is embraced. Modernity offers a very different kind of nothingness, much closer to nihilism; one devoid of peace and bombarded with stimuli. The original Cowboy Bebop explored this problem; the remake embodies it. The godless purposeless existence was tragedy then and farce now. The fact that Cowboy Bebop 2.0 is, for all its flaws, by no means the most inept or cynical culprit of this culture, among endless remakes and reboots, only shows how abject the practise has become. It’s time to make it new rather than anew.