NFTs will neither save the world nor destroy it, but the fractures in its market reveal critical fixes needed in both the contemporary and crypto art space

Over the last year, the collision of art and NFTs has been discussed largely in terms of sales and markets, especially given the ongoing decline in cryptocurrency values, but the more interesting conversations have been about the impact each had on the other. Dialogues in the artworld that have wound through the last 60 years – on artist compensation, art criticism, contemporary aesthetics and how to contextualise them historically, institutional engagement with digital art, collective action, art centres and margins, and ecological concerns – have all been revisited in the context of this emergent technology. Blockchain technology values a decentralised and more equitable market practice, introducing a set of ideologies in keeping with many contemporary art concerns, while also challenging certain practices. But as established artworld participants engaged with these issues, they introduced a discourse steeped in history and theory, to critique easy claims towards a better model proffered by some in the NFT space. The collision, therefore, offered a critical lens on both.

If the crypto and NFT explosion of 2021 popularised the ideal of an intermediary-less, decentralised market for digital culture, the power of NFT market players became evident in 2022. One of the most widely used marketplaces, Open Sea, banned two collections mimicking Bored Ape Yacht Club and the Meta Birkin collection at the end of 2021 for potential IP violations, and subsequent lawsuits foreshadowed ongoing regulation internationally. NFTs – bits of code providing a unique ID to a digital artefact such that it can be distinguished from other potentially duplicate versions – make possible the automation of resale payments, sales parameters and other unforeseen new features. In April 2020, led by former painter and generative artist Matt Kane, many crypto artists successfully established a 10 percent resale royalty at Super Rare that became standard across NFT platforms, so there was a predictable outcry when Sudoswap launched in the summer of 2022 with no royalty framework, leading to a debate about platform and collector support of such payments. This fracturing of support for royalties has ramifications across the artworld as new businesses like Fairchain and Arcual seek to enable digital certificates and payment for secondary sales of physical works.

With the fall in cryptocurrency values, an exodus in trading cartoony collectibles left many wondering if NFTs are finished. But the steady stream of projects and self-generated criticism reveals new level of attention within the NFT art scene. Two online magazines launched at the end of 2021 and early 2022 respectively, Outland and Right Click Save, led by former editors from established artworld magazines (Art in America’s Brian Droitcour at Outland and Flash Art’s Alex Estorick at Right Click Save), are developing an intellectual discourse for these digital art projects that mainstream media have been unable to articulate. Critiquing projects by recognised artists as well as rising stars, they addressed the cultural and theoretical debates within the art and NFT landscape.

An iconography is slowly emerging that will likely guide how these digital artefacts fit into art’s discourse. In 2022 generative art became the ne plus ultra of digital art. Incorporating part of the cryptographic process in its creative code, generative art is seen as offering an artistic output native to blockchain, in contrast to so much work untethered to its contract on the blockchain; platforms like Art Blocks or Fxhash focus exclusively on this practice. One consequence of this has been the renewed interest in pioneer practitioners of algorithmic computer art from the last 60 years, such as Vera Molnár, Manfred Mohr, Harold Cohen and Herbert Franke (who joined Twitter aged ninety-four, to be inundated by over 15,000 fans at his first message), who have become unexpected celebrities. These artists have enjoyed museum and institutional exhibitions in the last year, providing a history of aesthetics and practices previously marginalised.

Meanwhile, museums have shown scholarly interest about the possibility of NFTs, with MoMA presenting salons and the newly rebranded Buffalo AKG (formerly Albright-Knox Gallery) accessioning work from its benefit auction Peer to Peer. Commercial galleries have brought artists known for NFTs into their roster, most notably when Pace launched a partnership with Art Blocks in June. The Tezos blockchain had lines winding beyond the booth for their talk series on NFTs during this summer’s Art Basel, and NFT-based online galleries like Feral File and Epoch are in their second year, critically lauded for the curated shows that rise above the jumble of platforms. Known artworld participants like Chris Lew, Dominique Lévy and Nato Thompson are involved with development studios – like Outland, Dminti or Artwrld (respectively) – to help artists into this new realm, frequently called Web3 for the way it seeks to disrupt the centralised black box practices of Web2, the participatory internet exemplified by social media’s data extraction for corporate profit. In July Christie’s announced at its annual Art & Tech Summit, focused this year on blockchain, that it was launching a venture-capital fund to support art businesses engaging emergent technologies like blockchain. Institutional commitment is no longer in question.

Distributed Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) emerged, espousing community through a decentralised and distributed voting mechanism enabled by tokens associated with the DAO, though they often devolved into popularity cliques or investment corporations. Contributors associated with London-based gallery Furtherfield presented five years of research on DAOs as a mechanism for mutual support in the arts in Radical Friends: Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and the Arts, a needed provocation for those on either side of blockchain’s hype or dismissal. The technology is spreading across industries but its disruption within art also means artists are thinking through its implications and providing visual case-studies that articulate its possibilities and problems; the artist Jonas Lund continues his Jonas Lund Token DAO (2018–), in which participants can vote on projects the artist would produce, thereby distributing control over his artistic practice; Unicorn DAO is a collector community responding to the under-recognition of female-identifying and LGBTQ+ artists in the NFT space, much as occurs in the mainstream art market.

Given its web-based network, NFTs were perceived as levelling the market, but reports gave the lie to that assumption. The disparate pricing for female artists became an increasingly obvious problem, with projects like Unsigned (2022) working to raise awareness of unconscious bias in buying practices. The Global South remains painfully disregarded, with rare overlap to the North American and European scenes, despite the steady stream of NFT conventions across these regions. Artist groups like Crypto Argentina or the accelerator Africa Here aim to increase interest and opportunities for artists whose sales have significant import for their native communities – no matter the market dips that fell the wealthy north.

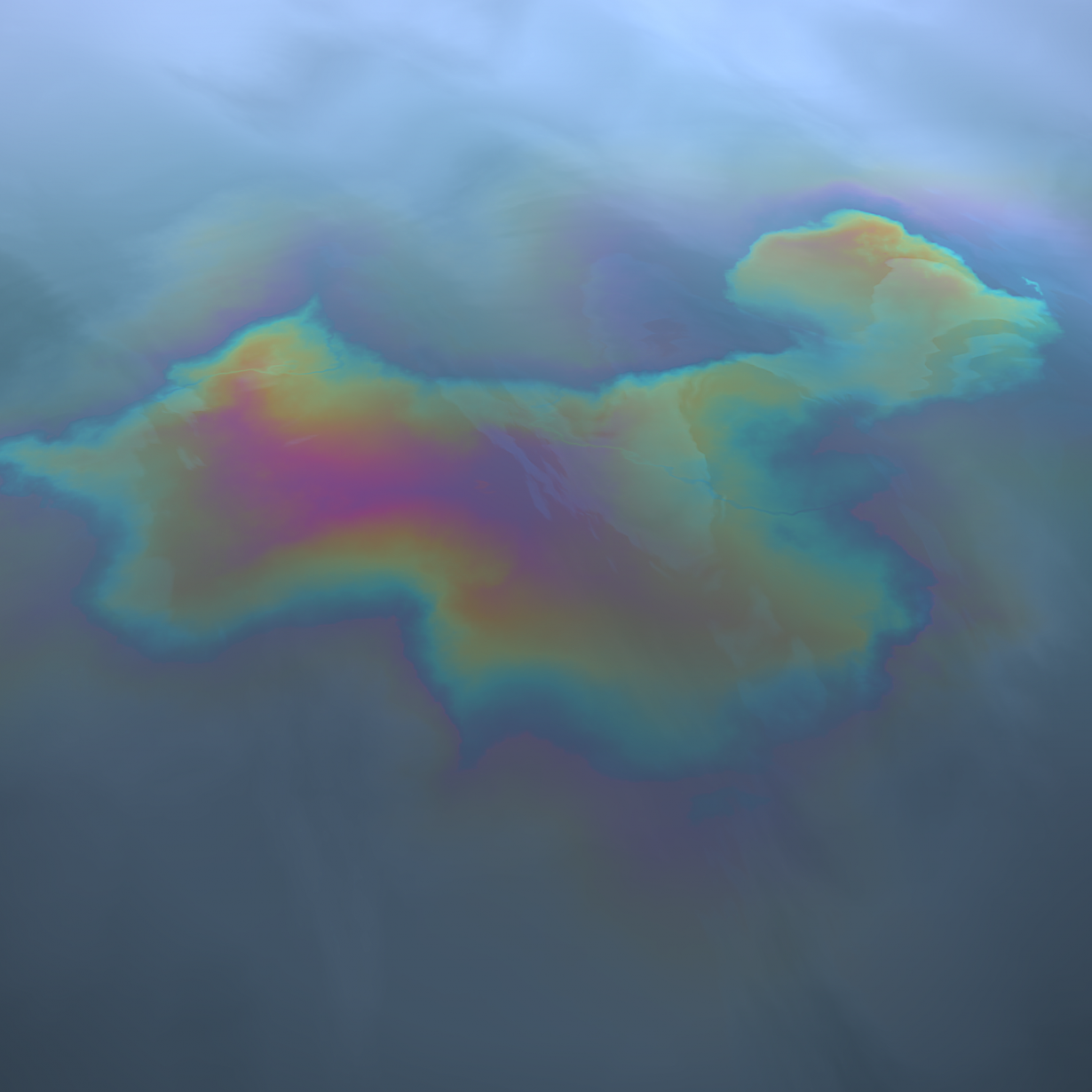

Lastly, the issue of the environmental impact of the most widely used blockchain, Ethereum, was put to rest through the Merge (when it transitioned in August from ‘proof of work’ to the far less carbon-intensive ‘proof of stake’). With the ecological effect of NFTs now in check, the hypocrisy of the mainstream art-market ignoring its carbon impact becomes more evident.

NFTs will neither save the world nor destroy it, but the fractures in its market haven’t impeded what it reflects back about the contemporary artworld, revealing fixes needed in both. If, to date, we have witnessed a collision of values and practices, then increased involvement by major participants in both contemporary and crypto art with each other’s institutions and ideas suggests a conversation less focused on denigration or market potential in the year to come. A more creative conversation would be welcome on both sides.