The filmmaker, artist and musician, who died on 16 January, was at once a mystic and a master of this beautiful little ugly life

On 23 December, my mother died, and although outwardly I have been relatively well-adjusted in the weeks since, inwardly I have been occupying a strange shadow world. Grief, with its tendency to split the sufferer in two between the past and the present, can cause memory loss, a certain mutability around identity; it induces wild shifts in mood, from derangement to apathetic numbness; it encourages the desperate survivor to look for signs and portents, until life itself begins to resemble a puzzle to be solved. One might say that it leaves you feeling rather like a character from the films of David Lynch: a man, say, who likes to remember things his own way, and not necessarily the way they happened (Lost Highway, 1997), or a woman in trouble (Inland Empire, 2006), or an actress from a small town who has just found herself in this dream place, and then subsequently realised that the dream place in question is a nightmare as seen from the inside (Mulholland Drive, 2001). On 14 January, I was listening to a podcast on which the brilliant director Jane Schoenbrun was discussing Lynch’s work, and a thought burst into my head, as spooky and acute as the feeling of suddenly slipping while cutting with a knife: what if David Lynch, my hero, were to die while I was already grieving? Two days later, he was gone. A coincidence, of course – I knew that he had emphysema, and that great swathes of LA, where he lived, were tragically aflame. And yet: of all the artists in the world, might he not be the most likely to send out a message through the ether in advance? ‘I’m pretty sure,’ he tweeted earnestly in 2010, ‘that I’m connected to the moon.’ I believed him. Maybe you did, too.

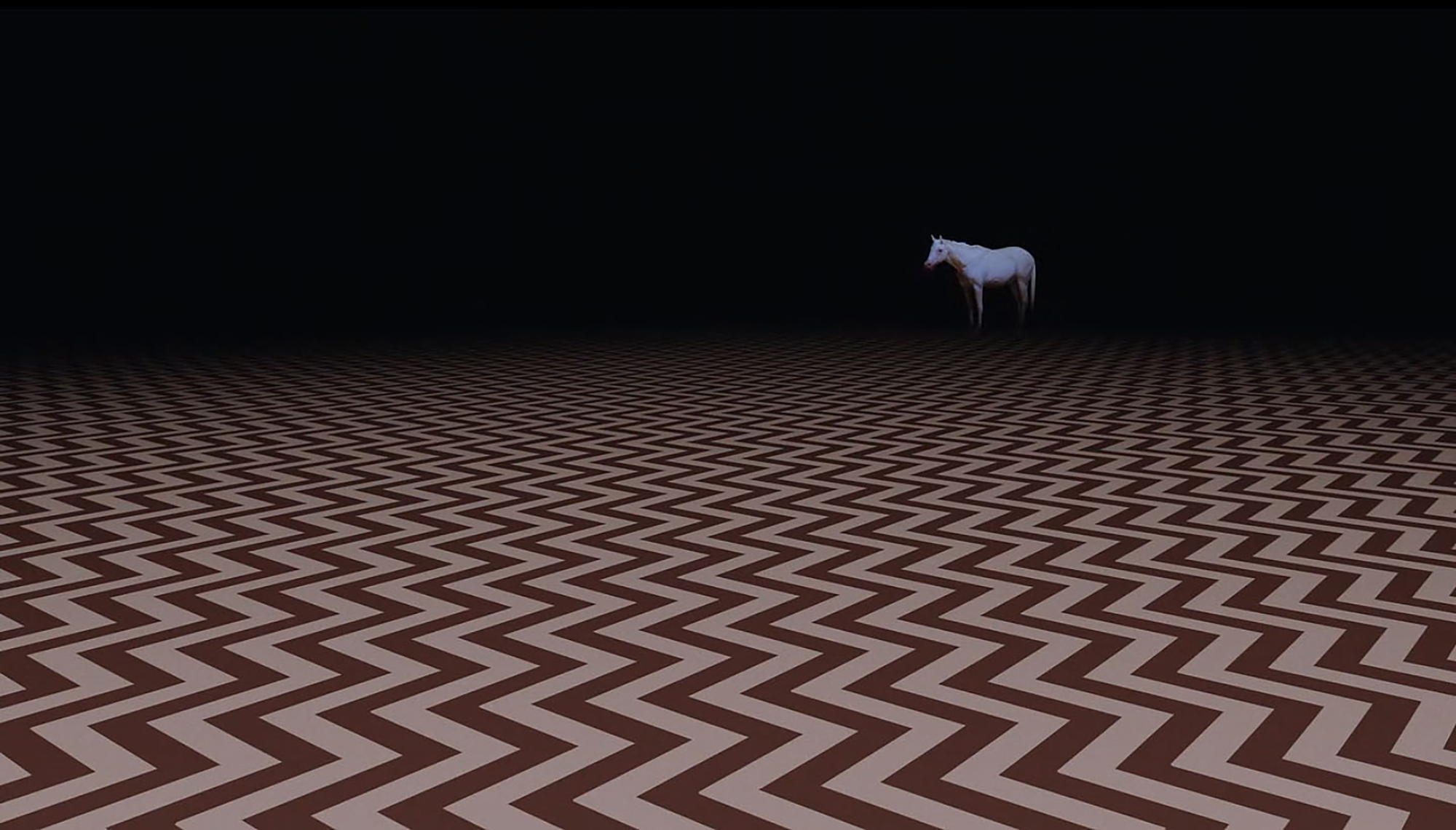

Here, per convention, I should tell you a few facts about David Lynch’s life, and his work – that he was born in Missoula, Montana, in 1946; that his middle name was, improbably, Keith; that for years, he cited only his birthplace and his onetime membership of the Eagle Scouts as his entire biography, and that while this was meant to be funny, it was clear that he did not necessarily see it as ironic; that he altered the rules of television in 1990 with his frightening, sometimes hilarious, supernaturally inflected soap opera, Twin Peaks, and that he rewrote them again in 2017 by releasing a third season of that show, subtitled The Return, which devoted fifteen minutes of airtime to a nuclear explosion and, in doing so, created one of the most beautiful and terrifying images ever committed to the screen. He directed ten feature films, beginning with Eraserhead in 1977, and ending with Inland Empire in 2006, and although he has received three Best Director nominations at the Oscars (The Elephant Man in 1981; Blue Velvet in 1987; Mulholland Drive), the only Academy Award he’s ever won has been a 2020 honorary Oscar, meaning that – I am sorry to say – the Academy Awards are officially irrelevant. He had, always, a terrific head of hair. He married four times, even though he often said that he was too busy with art to be a husband – probably because by all accounts, women simply could not stop themselves from falling, helplessly and irrevocably, in love with him.

Many of us adored him, too, albeit in a different sort of way. I began by mentioning my mother’s passing not to be cheap or mawkish, but because at present, I feel as if two of the pins that were holding together the fabric of my self have been removed in quick succession. My mother gave me my voice, and she encouraged me to love the written word, but Lynch was the one who bestowed on me an idea of what language might be used for at its dizzying outer limits – what might lie beyond the considerations of the concrete world that it was worth giving a name to. ‘The film is the talking,’ he once said to an interviewer, trying to point out why he did not feel the need to explain the inexplicable, or to offer solutions to the narrative ‘problems’ of his haunted, hazy sexual fables. I knew what he meant. The films talked to me, teaching me new tongues even when almost no words were being spoken – when everything had been boiled down to abstract gestures and zen koans. Performative femininity, and the actress as a metonym for womankind; doubledness and doppelgangers; the uneasy comingling of violence and sex, sometimes in ways that were deathly, and sometimes in ways that were erotic. These were some of his fixations, and as I first tore through his work in my youth, they became my fixations, as well. I know that some female viewers found his insistence on repeatedly depicting acts of cruelty against women distressing and lurid, and perhaps even sexist, and I would not deny them this reading. I never felt this way. For me, his endless return to the well of male sexual violence never seemed approving, only disbelieving, as if he were circling back to the crime scene of the American Dream to try and come to terms with the perpetual, sinister containment of this particular evil inside it.

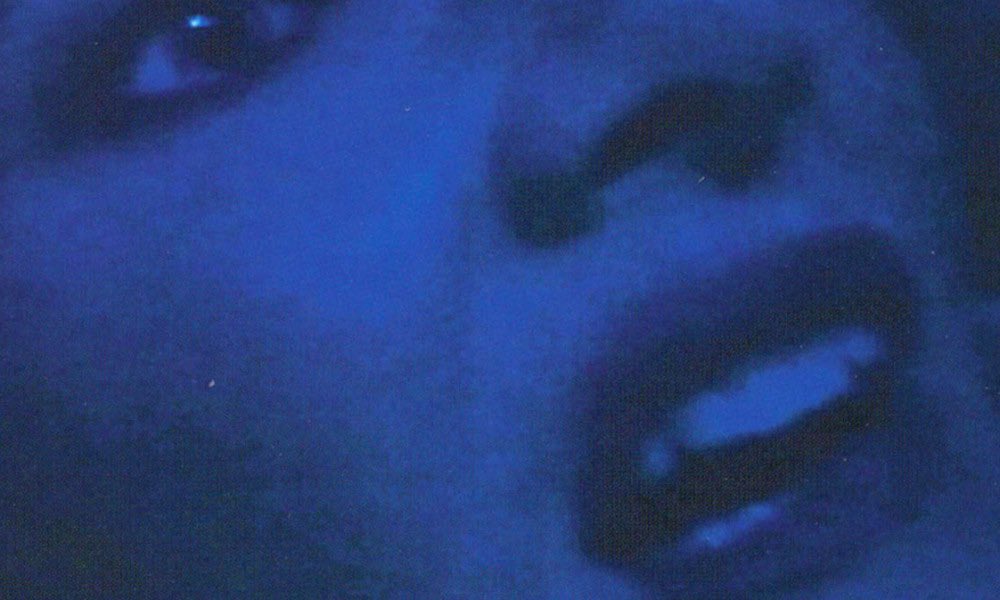

His last three major onscreen projects are, by my estimation, his best work by some margin: 2001’s Mulholland Drive, 2006’s Inland Empire, and 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return. If it is unusual for an auteur to produce their strongest output in their twilight years, David Lynch was the exception to the rule because he never once belonged to the present. He claimed to take dictation from the universe, and like his connection to the moon, this felt as if it might be true. (One of the best and funniest remembrances of him I have read in the last few days came from the writer Walter Kirn, who recalled being paid to profile Lynch, and then welching on the deal after Lynch himself spent the span of the assignment doing absolutely nothing, except smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee. ‘The “self” that was in there,’ Kirn explained, fondly, ‘was simply that of an artist in his off hours. Which is like the self of a vaccum cleaner in its off hours.’ What a brilliant image: the writer, hoping to see genius at work, and the artist merely waiting, calm and inert, like a mystic poised to hear the word of God.) Even when Lynch picked up a digital camera to make Inland Empire – arguably his richest film thematically, if not also his best – it was not in the spirit of moving with the times, but in the spirit of perverting technology: of drawing out the ghostliness inherent in the machine.

My beautiful little ugly thing, he used to call the over-the-counter camera he used to make Inland Empire in interviews, and the resulting brindled blacks and fuzzy edges made the finished product a beautiful, ugly thing, too. I think often of the part where Laura Dern’s dual-named, split-brained movie actress character Nikki/Susan, having been stabbed in the stomach with a screwdriver, bleeds out on Hollywood Boulevard, only for the lens to pull out and reveal that what we’re watching is a scene from a film-within-the-film. The crew applauds; the take is called. Dern, shaken to her core, wanders off in a daze, the working days of however many others continuing around her as she comes to terms with what felt to her, if only for a moment, like real terror, mortal peril. It has always seemed to me to be a perfect encapsulation of the experience of creating art, and especially of creating art in a context that is nominally commercial. It is easy to imagine that this was how Lynch felt when whatever message he was waiting for while he smoked and drank his coffee finally alighted on him, and he dutifully expressed it. It kills me that he wrote a spiritual sequel for Inland Empire, and that nobody financed it. Still, it occurs to me now that Dern’s ‘death’ scene is also a wonderful, if accidental, visual encapsulation of the alienating feeling of grief, and as I watched social media light up with tribute after tribute to my hero on the 16th, each post saying that he was also this person’s hero, and this person’s hero, and this person’s, I realised just how many of us would be walking around with the screwdriver of him lodged deep in our guts, and I felt glad. Strange, what love does.

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norfolk. Her latest book is Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object (2024)