The filmmaker, artist, musician and, lately, YouTube star, discusses parenthood, the pandemic and painting outdoors

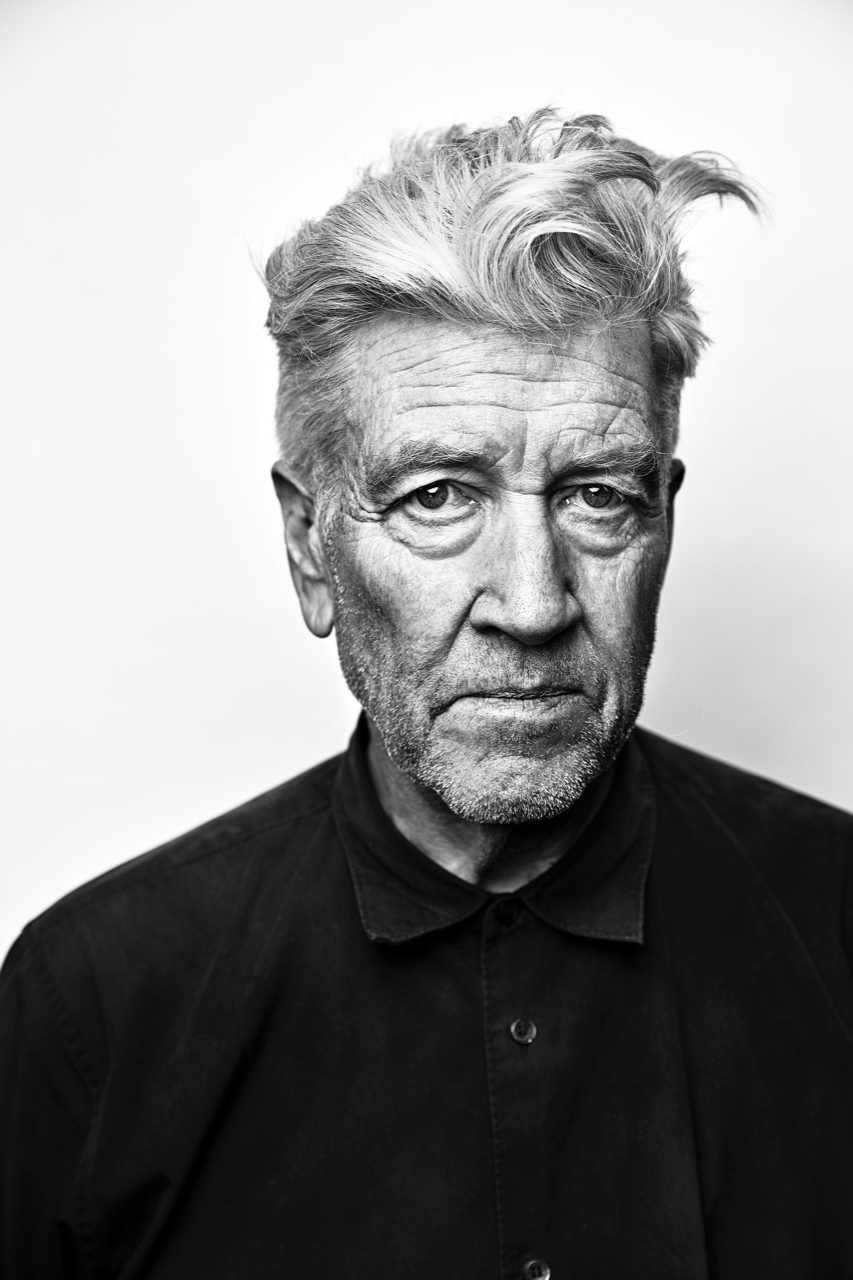

David Lynch speaks in the simple declarative sentences of a man who has spent a lifetime whittling away the inessentials of language. In interviews he often repeats statements he has made before, almost verbatim, as if he had long ago sorted his thoughts and sees no reason to continue fussing with them. On first listen, his statements often seem glaringly obvious, but on hearing them echoed, the phrases start to gleam with deep, perennial wisdom.

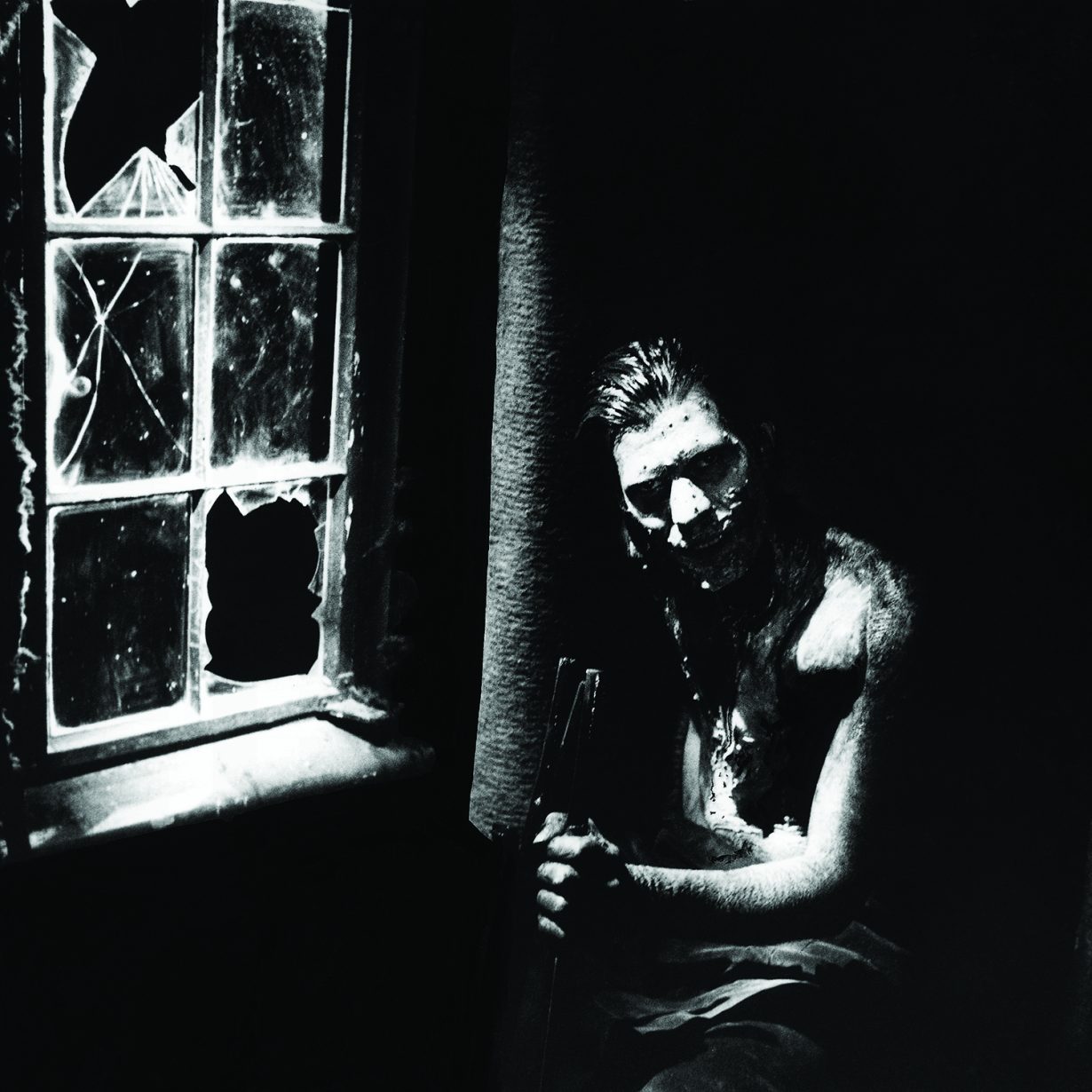

Since the 1970s, with the release of his first film, Eraserhead (1977), Lynch has refused intellectual forms of analysis surrounding his work. Instead he has become one of the great advocates for the pleasures of intuition and unresolved mysteries in art, forever denying the incessant inquiries of his pop-cult following. Likewise, his career has grown increasingly uncategorisable as he’s aged: in his late film-work, he’s experimented with technology (using grainy digital, consumer-grade camcorders on 2006’s Inland Empire), form (conceiving the 2017 television series Twin Peaks: The Return as a film) and distribution (releasing short films on his YouTube channel).

In the latter half of his career, Lynch has also developed the nonfilmic strains of his work, including his first passion, painting, as well as his furniture- and lamp-making practice, his music and, most divergently, the proliferation of Transcendental Meditation (TM). In 2005, he established the David Lynch Foundation, and has since travelled the world to lecture about the practice’s many benefits. One of his most pointed goals has been encouraging ‘peace-creating groups’ of meditators who can use their thoughts to send ripples of calming love throughout the world.

Recently, Lynch’s most public project has been his daily videos, which include narrated weather reports and an unexplained, ongoing lottery, for which he pulls numbered balls from a jar. At the age of seventy-four, he is one of the surprise YouTube breakout stars of the past year, illustrating the repetition we are all enduring in the age of the pandemic, as we watch the days float by and seek meaning anywhere, including in a sequence of random digits.

I spoke to Lynch on the phone in November. Already a self-described hermit, he has been quite forthright about his enjoyment of the lockdown and its benefits for his painting. Initially he agreed to talk for only 20 minutes, so as not to overly disturb his work schedule, but somehow the conversation rolled along for over an hour. In spite of my longtime admiration for him, the feeling of speaking to him was immediately easy and natural, as if I were discussing art with a kindly relative I was meeting for the first time.

Ideas First

Ross Simonini You used to say that interviews were traumatic for you. Are they still?

David Lynch Well, when I was younger I couldn’t even talk in an interview. So they’re not as traumatic as they were, but I still don’t ever talk about the meanings of things.

RS Why was speaking hard back then?

DL Because I came from the world of painting, which is more of a wordless thing. I was deep into that. And I didn’t even realise that I couldn’t talk until they asked me to do it. But I didn’t want to say anything anyway. So it was OK.

RS Do you have a conflicted relationship with written language?

DL I write to remember. I always say: write down the idea in such a way that when you read it again the idea comes back in full. So a script is for getting the ideas down, but it’s not the final thing at all. It’s to remind you of the idea, which could be much more full than what the words actually are saying. For instance, the script has no sound to it. It’s just ideas.

RS You talk about ideas often – the beauty of them, the danger of them, and how the process of an artist is like fishing for them. For you, what is the definition of an idea?

DL They’re thoughts that hold everything: the sound, the mood, all the information.

RS Are ideas more developed than regular thoughts?

DL Some thoughts are just more interesting than others. I’ll have an idea to go get a cup of coffee, for instance. Or for a scene in a film. Or for making a chair. This is why daydreaming is so important to me. All the thoughts just flow.

RS Do you ever start working without an idea?

DL You could do that, but as you go up to a blank canvas, as soon as you pick up a brush, you choose a colour of paint and you think about putting the brush somewhere – those are all ideas. So in a way, you can’t really do anything without ideas.

RS From the outside, it appears that your film career began with experimental work, then transitioned into the mainstream and then returned to experimentation. Is that how you perceive the trajectory of your work?

DL Well, it all depends on the ideas. Some things are very contained and straight ahead, like The Straight Story [1999], which is not something I wrote. And some things are more abstract. I guess when it’s more abstract, you could say it’s experimental, but it’s not really experimental, in a way. Ideas come and form themselves to be that way. The reason you might see Inland Empire as more experimental, for example, is because of the camera I was using. It seems like an experimental film because it’s a low-res camera, but it’s not, it’s just like every other thing, though the ideas are a bit more abstract.

RS So you’re making the distinction between abstract and…

DL Concrete.

RS It has nothing do with age for you then?

DL Just ideas.

RS But are the ideas that come to you different based on where you’re at in life?

DL They’re always different. It’s like, there are all these different girls, but one of them comes in and you just say, well, man, that’s the one! And so that’s the girl you go with. And it’s love.

RS Do you ever conduct research for generating your ideas?

DL I’ve gotten ideas from my oral pathology book. It’s the study of the oral cavity.

RS This is a book you turn to often?

DL It’s my number-one book! I’m part-way joking, but not really. I love my book on oral pathology. But if you read this and then you get some books on oral pathology, it might not be your cup of tea.

RS Do you read anything else repeatedly?

DL I don’t read. I like to daydream. I have read books, but very few.

RS The O.J. Simpson trial had some impact on Lost Highway [1997]. Do you look to the news for ideas?

DL Everybody watches the news these days. Normally I wouldn’t watch the news so much, but right now it’s kind of interesting.

RS You’ve often said that artists have to be selfish. Do you think that makes art a morally fraught territory?

DL It’s not just artists. It’s anybody who is into whatever they love. A lot of times people don’t love their profession, but whatever they’re in love with, they want to do it. And you have to have the time and space to do it. And so it precludes a bunch of things. It’s not a sacrifice. It’s just the way it is.

RS How has parenthood related to this selfishness for you?

DL Well, man, I got four kids. I never wanted to get married and I never wanted to have children. I’ve been married four times and I’ve got four kids. So it’s a torment. But once you have a child, the second you see them, you’re cooked. You fall in love with them and it’s a different world. And there’s not much you can do about it. But it’s a great thing. And that’s a torment because it does affect the work and it’s definitely a conflict. Definitely. The trick is to be with people who understand, and I’ve been really lucky. I’ve had great wives and great kids.

On The Other Side

RS How do you conceptualise a continuing story versus a closed form like a film?

DL The closed one has a form, and it’s called a feature film. The open one has no form. It’s got the possibility to go on forever, and it’s thrilling because it allows for magical things to happen. You’re going deeper and deeper into this world. Ideas are flowing and it could go anywhere. And that’s a beautiful thing.

RS Which is Twin Peaks: The Return?

DL It’s an 18-hour film. You could see it all at once without the opening credits each time. Stick it together and it’d be a long film.

RS Does it bother you that viewers feel the need to resolve the mysteries of Twin Peaks rather than allowing them to be unresolved?

DL I always say that people are like detectives and our lives are filled with clues. Some people wonder and look around and they take what they see and try to figure out what it all means. And they reach different conclusions. We are all like detectives, trying to figure out the meaning of life. And the same thing goes for film. You want to find a meaning – at least some people do. But now the world goes so fast. It’s just screaming on the surface loudly. And there’s not that much time for people to contemplate things and daydream and ponder.

RS I wonder if the pandemic has changed that.

DL I think it has. It has slowed things down and people come face-to-face with themselves and it’s scary. People are going nuts and they’re looking for any entertainment or any kind of thing to escape just being by themselves and thinking about things. And we’re all sorta like that. It’s really tough to be on your own. Because it causes something to happen. Things slow down and you find yourself with yourself. But I think something really good is gonna come on the other side of this pandemic and all the changes that are going on. A good time is coming for us all.

RS It’s a transformation.

DL That’s exactly right. It’s a necessary step to get somewhere that makes more sense.

RS I’ve been watching your weather reports and ongoing lottery during this time. Do you see these activities as an ongoing performance?

DL I see it as a torment. I have to do this every day. The good news is, there’s a lot of great people on my site, David Lynch Theater. They’re just a good bunch and they like the weather report and the number each day. And I want to give it to them.

RS Can you make it less tormenting for yourself?

DL Once you get used to something, it’s hard to give up. I could say, “I’m only going to take care of one every week, not every day,” but then it doesn’t work out for me.

RS Are you making music during this time?

DL Well, my dear friend Dean Hurley moved to Virginia, so I don’t have an engineer to help me. I can paint on my own, but I don’t know how to run the studio, so I need an engineer. So it’s a quiet time for music. I got a full-blown studio, but I don’t have any money to pay someone to work it, because there’s no work right now. So we’ll see what happens on the other side of this transition.

RS So with music, it’s a process where you have the ideas, but somebody else is there to realise them.

DL For the technical side, yes. I know a lot of musicians work on their own, but I’ve always worked with other people. And I love it. But when there’s a combo, like when I worked with Angelo [Badalamenti] or with Dean, it comes out different. Music is a magical thing.

Like Mining Gold

RS Painting is more of your solitary art, then. Are you able to fall into a trance while doing that?

DL Yeah. You’re in the zone. Time stands still. And when you make a film, you’re just in that zone for a very long time.

RS Do you mostly paint outside?

DL I’ve painted in different cities, but in LA, my studio is basically outdoors. Painting involves things that are toxic. You want it to be able to do certain things, so it’s better to have an outdoor studio.

RS Does the outdoor light affect how you paint?

DL Different times of the day have different light in LA, but when it’s blinding golden sunshine, it’s not always perfect for painting. I think the place is really important, so I do a certain thing here in LA, but I’ve also done paintings in Paris that are quite different. In different places, all the senses are sensing different things and the painting comes out different.

RS A lot of your work in television and film bears the mark of your conflict with the medium and the industry. Do you feel a similar struggle with painting and the artworld?

DL I struggle like crazy with painting. It’s like mining gold. You hit a vein and for a while, you’re just bringing in the gold. Then the vein runs out and you hope there’s more gold, but you’re digging through rock and there’s just no gold. And you keep digging and then eventually you find it. But it’s tough going from one vein to another. And that has happened many times with a painting, where I burned out that last vein and I’m looking for the next gold. But every medium is different. Every medium is infinitely deep and every medium will talk to you. Once you start working in that medium, it starts talking to you and it teaches you how it works and what it does. And then ideas start flowing in that particular medium.

RS Do you work on multiple projects during the course of a day to keep the ideas flowing, or do you focus on one project for longer period of time?

DL It depends. There are days when I would do two or three different things, but when you’re into painting, heavy into it, that’s pretty much it for those days. And that’s the same with anything. When I’m working on a feature film, that’s all-consuming. There’s no room for painting. There’s no room for anything else. And if you’re really into one medium, chances are you’ll be in it, day after day, until you burn it out.

RS Do you work continuously all day long? Do you have periods in the day where you don’t work?

DL You work all day. I mean, if you were to see me, the actual working-working might not be that much, but the thinking goes on all day long.

RS Are all these different mediums part of a single unified artwork, or has it all been a series of individual experiments?

DL They’re all experiments. It’s a blessing that there’s so many different mediums for us to enjoy. There’s just so much pleasure in every one of them! And when you get frustrated you go to the next thing, and that’s the only problem ever – that writer’s block. You need ideas. That’s why I always equate it to fishing. You just have to have patience and put the line out there and the ideas will come. The ideas will come!

Ross Simonini is an interdisciplinary artist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast, Subject Object Verb.