The artist’s photobooks challenge a Western art-history of portraiture to create ‘an ever-expanding mythological extended family’

Lives are bound together in a collection of photographs. Two young girls, dressed identically, sit on a sofa: one looks directly at the camera, her painted lips pursed in a pout; the other, her sister perhaps, looks slightly down, as if caught in a daydream, her attention elsewhere. A woman dressed in a pink swimsuit smiles coyly at the viewer as she sits on her topless beau’s lap, locked in an embrace against a backdrop of lush foliage, their neat high-tops, seemingly out of place within the natural environment, appear like a status symbol. A baby, just born and still covered in amniotic fluid, is wrapped in a towel as their exhausted mother gazes down, her partner’s disembodied hand held protectively around her head. Another woman wearing a silk purple dressing gown, possibly a mother, styles the hair of her nude daughter who sits in a chair in their living room – in one corner stacks of CDs and DVDs, and on the other side of the room, display cabinets upon which stand a porcelain doll in Victorian dress, candles, and what appear to be a pair of graduation certificate folders proudly taking their place among framed family photographs.

Questions of Black agency, dignity and self-determination are addressed in the work of American artist and photographer Deana Lawson. Drawing from photographic genres such as studio photography, documentary, family photographs and the tableaux, Lawson’s large-format colour work typically portrays members of her local community in Brooklyn, as well as strangers, in scenes that reflect on family, love, selfhood, beauty, pride and the Black aesthetic. It’s part of an ongoing project to visualise a standard of values that, while

informed by certain stylistic qualities, are distinct from and challenge those that have been imposed by a Western art-history of portraiture that has historically excluded Black bodies.

Lawson’s work operates within a canon of Black photographic portraiture that has been, prior to the twenty-first century, largely overlooked by art-historical academia, but which dates back almost to when photography first became a publicly accessible medium. In the United States the Goodridge Brothers set up one of the earliest Black photography studios in York, Pennsylvania, in 1847, which relocated to Saginaw, Michigan, and made daguerreotypes that reflected individuals and families in a dignified manner that opposed those taken for anti-Black propagandistic purposes; Frederick Douglass, a social reformer and freed man who escaped slavery in Maryland before settling in Rochester, New York, and the most photographed American of the nineteenth-century, delivered the ‘Lecture on Pictures’ in 1861, arguing that photographs had the power to define a person and reveal their humanity. This was during a time in which that subject was informed by ethnographists and naturalists like George Gliddon, Josiah Nott and Louis Agassiz, who had made a case for a hierarchical polygenism by ‘proving’ racial inferiority via a taxonomy of physical traits. During the same decade, former slave, Abolitionist and womens’ rights activist Soujourner Truth used portraits of herself in the form of cartes de visite (popular at that time among Civil War soldiers who kept them as reminders of their sweethearts and families, but which were also used to spread political messages) to promote her speeches advocating for the end of slavery. Both Douglass and Truth believed in the power of photography as a medium that allowed self-representation but that also visualised empowerment and defiance for a part of American society more used to this subjecthood being stripped away under the white gaze: their portraits were the early picturings of basic human rights and social equity.

Fast forward more than 150 years and Lawson is photographing an empowering, dignified and visually complex Black aesthetic that celebrates African-American culture, tradition and spirituality, as well as those in locations specific to the Black diaspora such as Haiti, Jamaica, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia. The result, perhaps best showcased in her 2018 Aperture monograph and forthcoming MACK photobook that will accompany her first survey show (opening at ICA, Boston, and touring to other institutions), is the creation of a kind of universe that makes connections between Black communities in what Lawson calls ‘an ever-expanding mythological extended family’. That mythology, in part, is due to Lawson’s keen eye for constructing scenes that blend her subjects’ lived experiences with the imaginary – at once picturing them in the reality of their own homes and domestic spaces, composing intimate scenes between strangers, and recalling stylistic tropes from art-historical paintings.

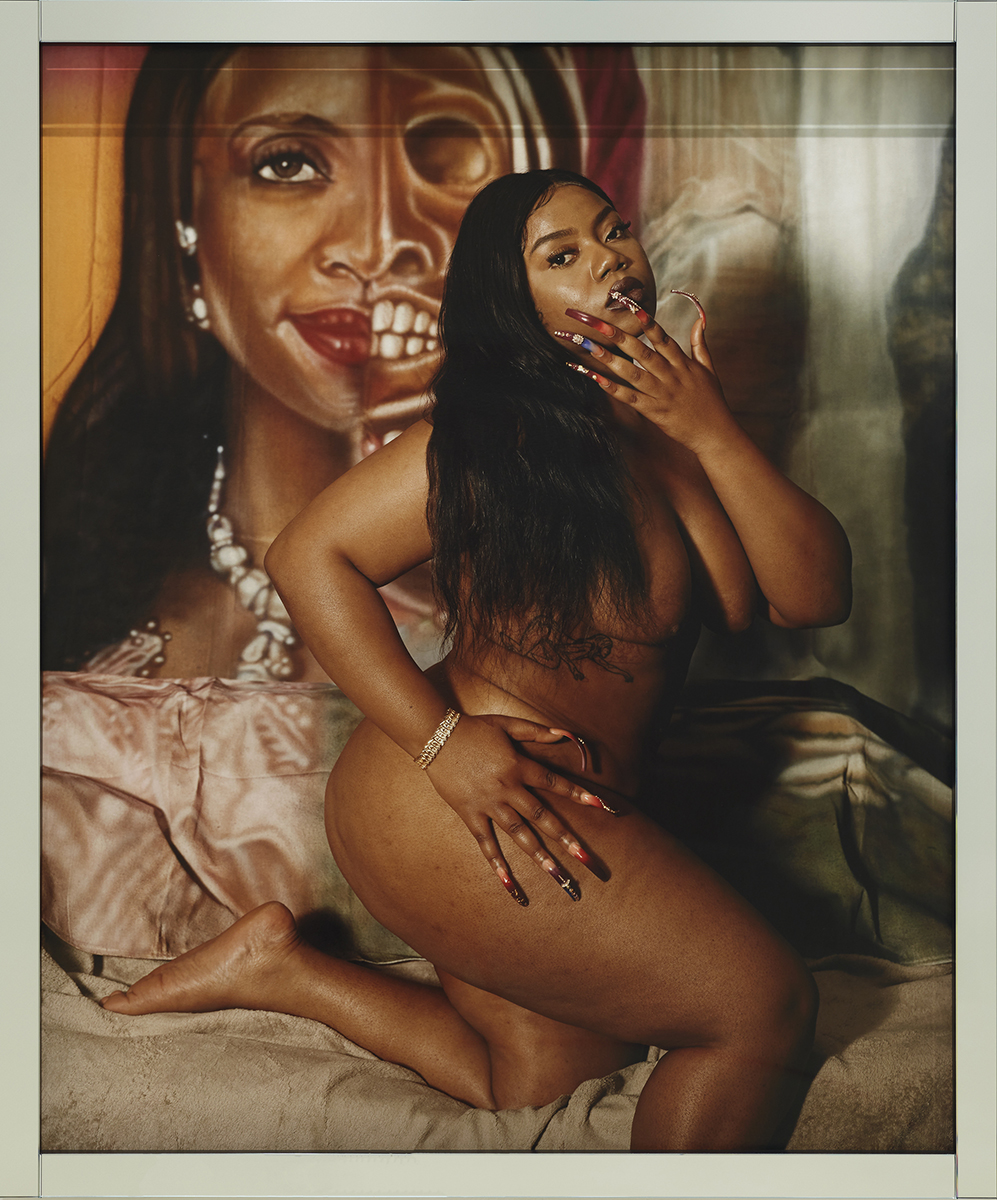

Take, for example, Holy Mami (2021), in which a woman poses nude before a mural of the Yoruba goddess of weather Ọya; like the majority of Lawson’s subjects, she looks directly into the camera, half kneeling on a sofa draped with a pink and beige satinlike material, one hand set against the top of her thigh, the other resting against her tilted, inscrutable face. Adorning her fingers are long, brightly painted acrylic nails. In recent years, artificial nails and nail art have become a beauty trend popularised by celebrities like the Kardashians, whose whiteness has made acceptable what was for many years regarded as a look associated with the ‘ghetto’, and as such ‘inappropriate’. (Indeed, record-breaking athlete Florence Griffith Joyner was mocked by the US media for the four-inch nails she wore during the 1988 Olympics, despite winning three gold medals.) Lawson’s photograph, however, shows that acrylic nails are a means of self-expression and pride – in much the same way that jewellery in Renaissance portraiture, for example, would be included as a signifier of one’s stature, wealth or family.

Gold jewellery appears in Chief (2019) and Black Gold (“Earth turns to gold, in the hands of the wise,” Rumi) (2021): in the former photograph, made in Ghana, a man sits in his living room wearing gold necklaces, bracelets and a headdress associated with the Asante Empire; in the latter, another man holds up an array of contemporary gold necklaces. For Lawson, the gold jewellery represents a duality in Black culture, one that has a deeper ancestral meaning: “When I was researching gold in West Africa, particularly the Ivory Coast, Senegal and Ghana, and most notably in the Asante Kingdom, I realised that the way gold was worn by chiefs and the Asantehene king is similar to the ways in which young Black men in hip-hop culture have worn these amazing gigantic medallion pieces. Those big gold necklaces – that’s Asante right there,” Lawson explains. But in Black Gold, Lawson’s decision to collage in a holographic image of Ron Finley, a Los Angeles-based food-access activist, who is working to renature and raise awareness of ‘food deserts’ in his city’s South Central area, creates a further multiplicity of meanings. “A mentor once said, ‘You can’t eat gold and you can’t eat diamonds,’” recalls Lawson. “I wonder about the ways we value these things in society when, in the Anthropocene age, our planet is becoming more uninhabitable. When one is able to grow one’s food, what does that mean in terms of power? And what if the subject in Black Gold was selling collard greens and herbs, making just as much money as he is by selling those necklaces and Ralph Lauren cologne? It’s a question of what value and power means now.” (Until now, of course, ‘black gold’ is widely used to describe crude oil.)

Yet more material visual affiliations with classical Western paintings can be found in Ashanti (2005) and Sharon (2007), in the folds of the curtains that behave as a backdrop for the two nude women. There is something of Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647–51) in Ashanti, in the pose of the woman lying on a bare blue mattress, yet instead of an insular passive subject gazing at her own reflection, Ashanti turns her head to meet the viewer (or voyeur) eye to eye. That prolonged eye contact in non-Western cultures tends to be regarded as confrontational and a challenge to authority lends the sitter’s expression in this photograph a further magnetic intensity. Non-material associations, too, are made visible in Signs (2016), a photograph of four topless men sporting tattoos, whose bodies are dramatically illuminated in the camera’s flash – the chiaroscuro effect reminiscent of a Caravaggio painting. Each has their hands raised in various gestures at the camera: two men do a thumbs down; another points his middle finger into a space between the fingers of the other hand; another holds his hands in parallel, forefinger tips and thumbs pressed together, as if holding an invisible sheet of paper or cloth, banknotes or the strings of a puppet. Three of the men’s faces are obscured, either by their gestures or by an anonymising pixilation, while the fourth man, his arms raised higher than his fellow subjects, stares directly at the lens, his chin jutting in a strong-willed expression. The issue of hand signs has a contentious history of being associated with gangs – in 2014, teenager Dontadrian Bruce was suspended from school (in one of a number of similar incidents experienced by African-American teenagers) following a photo taken by his mother and published on social media, in which he held up three fingers to reflect the number on his football jersey. The school’s quick judgement that the sign was associated with the Vice Lords, a Chicago-based gang, brought to light the racial bias surrounding hand gestures. In Signs, the focus on the subjects’ hands as signifiers recalls a historical use of gesture in paintings, which comes from a system established in the ancient Greco-Roman era known as Chironomia – though these are related to rhetorical and oratory practices, the gestures found their way into paintings to denote personal status as well as spiritual intention. In Signs this non-verbal form of communication brings notions around language, interpretation, translation and the use of secret codes to the fore: the meanings of the signals are known by some, yet impenetrable to others.

Collected together in both photobooks, these photographs are further enriched by a format reminiscent of a family album. It’s a photographic style that serves as a broad frame of inspiration for Lawson, whose father was a prolific image-maker of their own family and friends, a practice made more widely affordable by Kodak’s development of cheaper film and disposable cameras (Lawson’s grandmother and mother were also employees of the Rochester-based firm). Multiple depictions of sisters (Roxie and Raquel, 2010, sit back-to-back on a bed positioned against a bright yellow wall, their arms raised behind their heads, fingertips touching), lovers (Binky & Tony Forever, 2009, a couple embracing on a gold-duveted bed beside which a green drinks bottle contains yellow flowers, the scene partially reflected by an oval gilt-framed mirror), mothers (Daenare, 2019, pregnant and reclining nude against a stairway, decorated by floral and spiral motifs on the tiled floor, the painting of flowers on the wall and the curling tattoo at her hip – the image’s softness punctured by the ankle monitor strapped to the base of her calf) create a sense of unity, and at the same time they are undeniably individual in their commitment to perform a sense of self. Lawson photographs every stage of life, from a newborn held in a man’s arms (Sons of Cush, 2016) to Monetta Passing (2021), a funereal portrait of a woman lying on a bed of purple satin while a mourner sits beside her – the two images quietly connected by the array of framed family photos displayed on side-tables. By collecting these images in photobooks as extended family albums, Lawson blends vernacular and art photography in a way that effects a fundamental shift in our perception of the normalised didactics of Western art history, and in doing so, confronts, challenges and reframes those tropes and iconographies to shape a contemporary Black aesthetic that is bold, affirmative and loving.

Work by Deana Lawson is on show at the ICA Boston from 4 November through 27 February; Deana Lawson (2021), published by MACK books (£35) accompanies the exhibition at ICA Boston; Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018) is published by Aperture (US$85)