There it hangs: a golden earring in the shape of a piece of miniature drooping armour, placed in a tiny hole in a slender triangular metal structure coming out of a corner of the room. The ‘lock’ is attached to the back of the pin; the whole thing hangs just as it would from an earlobe. The earring is alone, separated from its twin. In fact, the separation is temporary; the other earring remains with its owner, who will not use it until the two are reunited.

The earring and its structure are installed in an official-looking building, one of the four main venues of the ninth Bienal do Mercosul, titled Weather Permitting and beautifully curated by Sofia Hernandez Chong Cuy and her team in Porto Alegre. It is one of four works in the Bienal by the Mexico City-based artist Tania Pérez Córdova.

With funding being the most prominent topic among colleagues today, it is crucial to spend more time with art itself

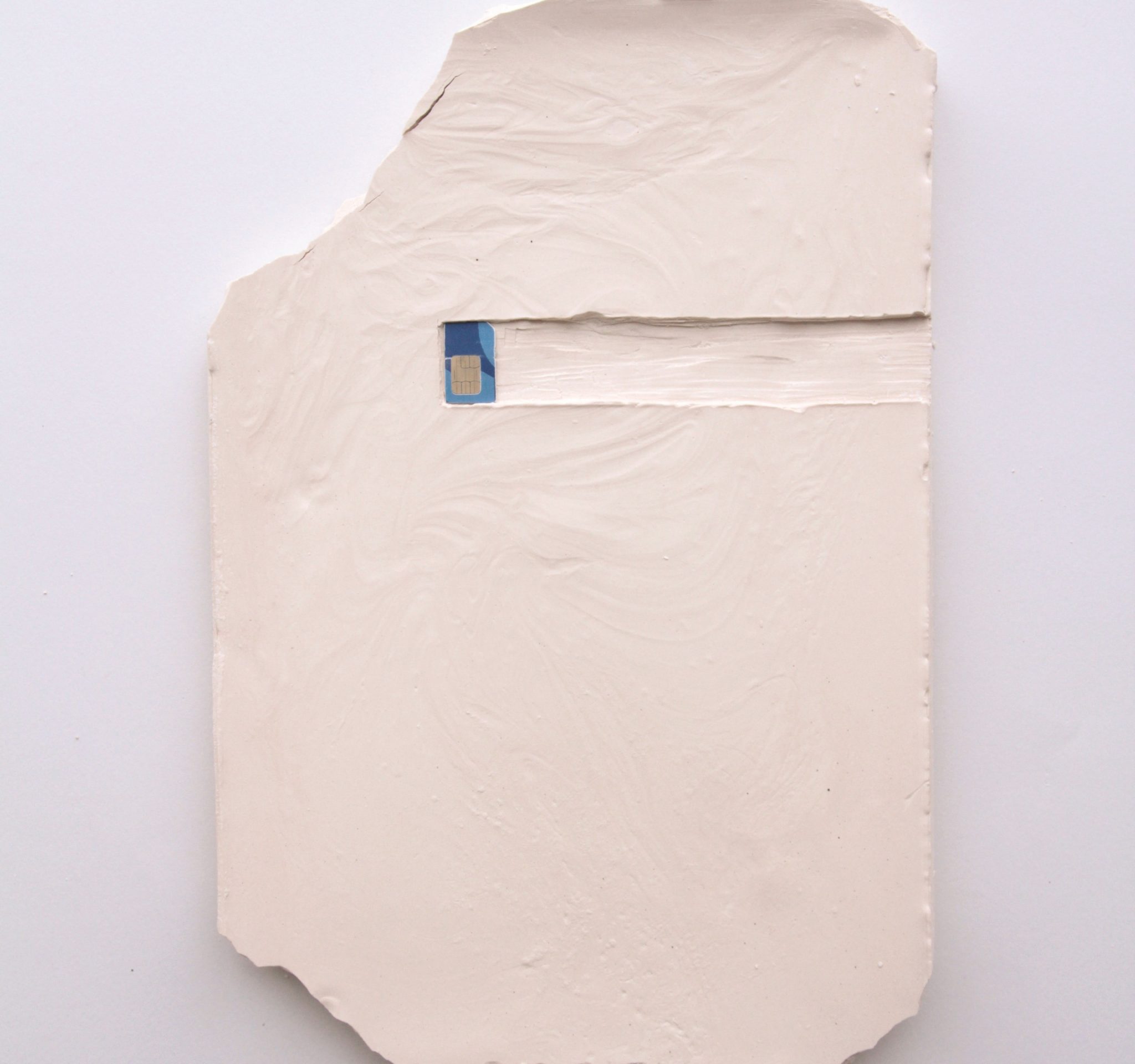

All of them contain a borrowed object, which has temporarily left a significant part of itself, or its context, behind. They share the title Things in Pause. In addition to the earring, there is a sim card embedded in porcelain, a shirtsleeve severed from the shirt itself and inserted into pine wood, and a piano key on a journey of its own. After the exhibition the objects will be returned from whence they came. In case of a sale, the buyer is requested to find an equivalent object to incorporate into the framework devised by the artist.

Pérez Córdova puts objects on hold, placing them outside of their quotidian existence as (temporary) art objects. In a way they are being put to the test, both as plain objects and as art. So what happened to the earring, a delicate and intimate object (belonging to the artist’s grandmother, I learn while reading up on the work), in this otherwise large-scale biennial exhibition?

In addition to modestly electrifying the corner where it was installed, next to work by, among others, Cao Fei and Mario Garcia Torres, Lost Gold Earring said something about how art can operate today: that objects and actions can commute between contexts, and that the transitions from homebase to artwork and back to homebase can allow for imaginative yet concrete associations.

It is tempting to introduce the idea of the quasi-object into this query. The quasi-object is less psychologically charged than a transitional object, but nevertheless one that mediates between people. The quasi-object is not even an object, but neither is it a subject. And yet it participates in the constitution of the subject. When passed around, the quasi-object creates the collective – when it stops, the subjective ‘I’ appears.

A ball, for example a football, is the quintessential quasi-object, according to the philosopher Michel Serres. It is made for circulation, ‘weaving the collective’ while in motion. It remains ‘lifeless’, or not yet animated, as long as it is still. It has the potential of being both ‘being’ and ‘relation’, depending on its status.

On closer inspection, the objects in Pérez Córdova’s work are to some extent quasi-objects. They simultaneously connect and decentre; they form the basis of distinct works in and of themselves and they partake in the mediation between a number of other external entities. In the bigger picture, it is very likely that art itself is a quasi-object.

Having recently been invited to address some of the urgencies of the present in the sphere of curating at a symposium at the School of Visual Art in New York, art comes first on my list. Art as a quasi-object – a form of understanding that is more necessary than ever, as a horizon of the possible beyond the given.

I have a distinct feeling that we need to return to art itself, to focus on artworks and art projects in the wake of art institutions becoming more and more obsessed with themselves, curating programmes being preoccupied with curating, and curating students becoming stuck in curatorial pirouettes or symbiotic collaborations. Not that art has disappeared completely, but it has been pushed into the background.

This is problematic and yet understandable: in a place like Europe a paradigm shift has happened in terms of the conditions of production for both art and curating. The single most palpable feature of this is how funding structures have been transformed, largely without public debate. At the same time as the commercial art market is blossoming, public funding is decreasing, and at the same time the public funding that remains is increasingly instrumentalised.

With funding being the most prominent topic among colleagues today, it is crucial to spend more time with art itself, inquiring what an artwork does. Not what it can do, but what it actually does: how it sits in a specific situation in society, and how it operates from there. Pérez Córdova’s golden earring and its commuting character, its relying on future events, has stayed with me. I even started to wear earrings again, after a 15-year pause.

This article was first published in the December 2013 issue.