Lust for Life, the 1956 biopic of Vincent van Gogh, sees Kirk Douglas hamming it up as a tortured, misunderstood yet brilliant artist. Blue-smocked and patinated with picturesque poverty, the artist is figured as a visionary, someone outside the norms of society and far beyond the bounds of the market. The artist is cartooned as a romantic, if doomed, hero.

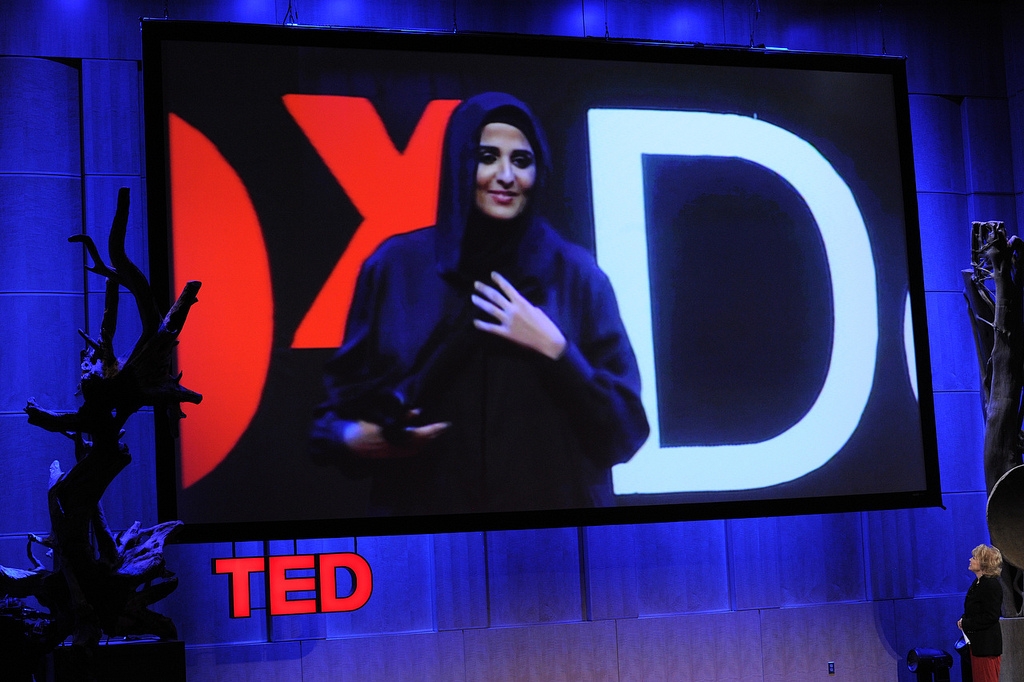

But if one were to characterise the figure of contemporary creativity, it would be a very different performance. It might be someone with a tech consultancy, a suit but no tie, and a TED-talk lanyard around his neck. In other words, ‘creativity’ is not a natural, innate quality, but a synthetic idea.

Creativity is, it seems, a central plank of the machinations of the modern world. We see it cited in the rhetoric of business, the future of cities, economic growth and government policy. It’s there in the creative class, an idea popularised by Richard Florida’s 2004 book, The Rise of the Creative Class, and often celebrated in the strange modern parables we know as TED talks. Indeed today we rely on so-called creative industries to drive our knowledge economies. ‘Design thinking’ is a term applied to management theory as a way to maximise efficiency.

There is a whole literature dedicated to this idea of creativity. In Alan Iny and Luc de Brabandere’s Thinking in New Boxes: A New Paradigm for Business Creativity (2013), the authors write that ‘true leaders must develop the capacity for radical originality: they must re-imagine and reinvent the world in totally unexpected ways. By doing that, they can create a culture that is open to creative risk-taking and an environment where failure is accepted as part of the creative process.’ You can read articles in Time and on The Huffington Post with titles like ‘What Can Jazz Teach Us About Business?’ or ‘How to Harness the Creative Mindset’.

You can go to events, such as the Motion Picture Association of America’s 2013 Creativity Conference, that convene ‘leaders from the world of politics, media, business and government to engage in a direct dialogue about the role creativity plays in our economy and in creating the workforce of the future’. You can take part in ideation sessions. You’ll become enthused with the idea that ‘creativity is not just good for a company, it’s good for a nation’s economy’, as the UK Design Council’s Graham Cox put it several years ago.

Creativity is remade as a form of value creation, a tactic that generates shareholder wealth

There’s something unnerving in all of this. It’s as though a coup had been staged in the heart of art-school culture by management theorists. This is taking the place of creativity as we once knew it. It’s creativity reimagined in the terms of business. Creativity remade as a form of value creation, a tactic that generates shareholder wealth.

It’s strange that this cult of creativity should be simultaneously so highly prized – fetishised, even – when the value of creativity in wider culture is becoming devalued. State support for the arts has been slashed in the name of austerity economics. But then that was a different kind of creativity – the old-fashioned, high-minded idea that culture might be something of value in and of itself, something whose ‘value’ might be measured in equally old-fashioned notions of the public good. Creativity as viewed through the lens of management speak, by contrast, is a form of competitive advantage, a means of advancing the private sphere.

One might argue that these new myths of creativity are not just an expanded idea of what might constitute creativity, but an attack on existing forms of creativity. Think of the parasitic relationship of advertising, perhaps the longest-serving ‘creative industry’, to fine art. Think of advertising’s proboscis nudging around, sniffing out repurposable ideas and images. Or think of the rhetoric of the creative class, whose belief in a kind of creative/ economic growth axis is phrased as the trickledown neoliberal future of cities instead of the proper planning of housing and communities.

Creativity is, in other words, an ideology. And the figure of today’s ‘creative’ is one that occupies the centre ground of one of the most powerful ideologies of late capitalism: the cult of the individual. All those qualities that were associated with old-fashioned (and equally ideologically constructed) creativity (see, for example, Douglas’s raging Van Gogh) have been bent into new arrangements.

Creative heroes and visionaries no longer stalk the Arles landscape with an easel over their shoulder. Instead, creative consultants channel these myths into corporate boardrooms and Powerpoint presentations, where their mantras of ‘disruption’, ‘revolution’ and ‘innovation’ simply fuel the monocultural globalised business model of neoliberalism. It’s enough to make you want to cut your ear off.

This article was first published in the December 2013 issue.