In 2008, Edgar Arceneaux showed a sculpture called Giant Fractures Glass Tripod, which featured a hunched skeleton painted in enamel on broken glass. The sculpture was the heart of an exhibition, also at Susanne Vielmetter, that attempted to make connections across a number of fields, ranging from biology, geology and history to religion and even the zodiac. Giant Fractures Glass Tripod was a direct reference to Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23) and To Be Looked at ( from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour (1918), placing a primal man or forefather to humanity in the place of Duchamp’s enigmas.

What Arceneaux wanted, it seemed, was to present an origin-of-the-world story, where art synthesised conflicting cosmologies by pointing to similarities in science and religion, which would hopefully transcend their fraught relationship and give a sense of something larger than themselves. The problem, at that time, was that the different sources (both scientific and religious) were poorly defined, and Arceneaux’s referential layering only made matters worse. The entire proceeding came across as simply a number of loose concepts set free inside a Duchampian funhouse with nowhere to go.

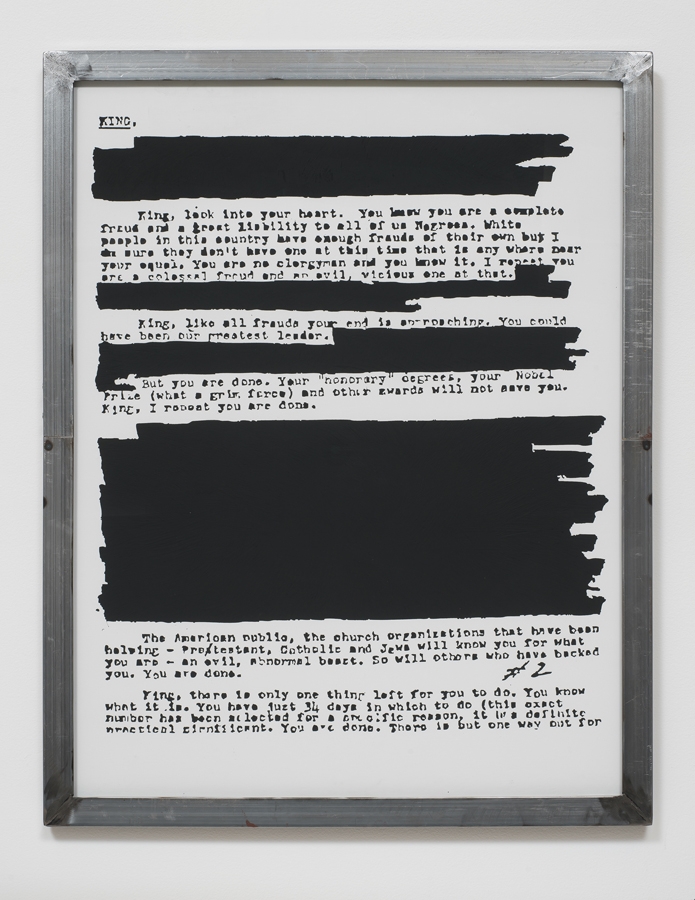

In Arceneaux’s current show, thankfully, the subject matter and the dilemma it presents are clearly stated. The exhibition grapples with two documents: one a redacted anonymous letter sent from the FBI to Martin Luther King, Jr, threatening King with the exposure of his marital infi delities if he did not commit suicide; and the other a statement by King’s daughter protesting the sale of his Nobel Peace Prize and Bible at auction.

Using these letters, the exhibition presents a complex portrait of the Civil Rights fi gurehead. At one point, Arceneaux (a top-notch draughtsman) simply draws King from diff erent angles. Copies of the letters are placed in vitrines and backlit. A number of windows hang from the sides of the gallery like didactics: some windows have the letters on the glass, others are surfaced with collages speaking to King’s complicated personal relationships, his controversial politics and the collateral material generated by his public rise. The crescendo of the exhibition is a video involving the primal man, King’s last speech and the music of Underground Resistance, all set in an abandoned Catholic church in Detroit.

Overall, the exhibition feels like a rebuke to Civil Rights museum installations or other manners of PR-approved storytelling. As an alternative to these thin rituals of packaged history, Arceneaux wants to keep the story intact, complete with its rough edges and enigmas, and fortunately his presentation is rich enough that one really does desire to understand King in all his complexity. In fostering this desire, Arceneaux’s thick Duchamp references then start to work with profound effect. Just as the glass in Duchamp’s Fresh Widow (1920) is darkened by black leather and Duchamp’s desiring machines ultimately grind to a halt, so our interest in King is heightened through Arceneaux’s presentation of King’s many paradoxes and the deftness with which King’s story eludes our understanding.

This article was first published in the December 201 issue.