The problems of the world weigh heavy on this exhibition. In its curation of this 31st Bienal de São Paulo, titled How to (…) Things That Don’t Exist (insert from the curators’ list of different terms into the blank, including ‘look for’, ‘recognise’, ‘fight for’, ‘use’, ‘imagine’), a five-strong collective, assembled by curator Charles Esche, is not interested in subtlety. Which is actually pretty refreshing. Instead they look to places where pragmatic struggles for survival outweigh philosophical or aesthetic absorption. There is, in short, a prevailing preference for the political suckerpunch.

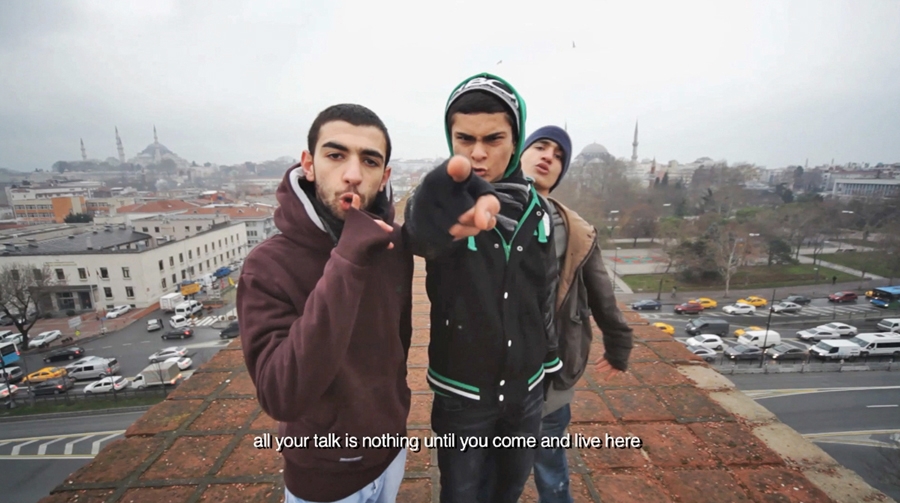

The motivations for such polemics are as varied as problems in the world. The angry, corrosive lyrics of Halil Altındere’s eight-minute ‘music video’, Wonderland (2013), one of the first works that the visitor encounters (at least aurally), sets the tone. Running through their native slum neighbourhood a Turkish rap collective rhymes boastfully of gunning down police. They spit out disgust for capitalism, for neglect, for regeneration. They parade their identities with a mixture of pride and anger: alienated youth, disenfranchised males, their Kurdish and Roma heritage a prison. The bassline echoes beyond the viewing room, offering an unintentional soundtrack to Ana Lira’s nearby sculptural installation, Voto! (2012–). Various tattered and graffitied election posters are transferred onto transparent Perspex panels hung floor-to-ceiling. The weatherbeaten nature of the original advertisements offers a cynical vision of government after the campaign promises. The alienation of Altındere’s Near East youth gets picked up in the expressions of Eder Oliveira’s mournful, emotionally wrenching wall paintings, in which eight young men – black and mixed-race, bare-chested, their arms held behind their backs – stare out across the Bienal’s ground floor. Beside the murals, a stack of crime supplements from the local newspaper of Oliveira’s hometown in the northeast of Brazil makes explicit the artist’s source material for the portraits.

Yet this is also a show in which one’s ability to thrive or survive is inextricably linked to identity. This notion defines Armando Queiroz’s dry but nonetheless worthwhile Ymà Nhandehetama (2009), a film made with Almires Martins, a Guarani activist, whom the viewer sees bathed in artificial blue light, addressing the history of his people’s oppression. We see identity struggled with in Nurit Sharett’s excellent 52 minutes of filmed interviews with Jewish people on the subject of matrilineality, Counting the Stars (2014): those who are able to relate their five generations of Jewish heritage are countered with new converts who heartbreakingly bemoan the alienation they feel within their adopted religion. This investigation into identity and activism continues throughout a vast landscape of works. Some are domineering – like the architecture structure erected by Indonesian collective Ruangrupa to host ad hoc workshops, craft activities and, on my visit, karaoke – and can be glimpsed from different floors of the ramped, open-walled Oscar Niemeyer-designed exhibition space. Others are given their own space, like Dios Es Marica (God Is Queer), a small, self-contained exhibition sited in a set of temporarily erected side-galleries. Here, work from 1973 to 2001, by four artists and collectives dealing with the queer body and gay activism, are presented. The late Spanish artist Ocaña’s is the most exuberant. A monitor shows the documentation of one of his carnival parades, staged during Franco’s dictatorship, which affronted its contemporary, conservative audience by rubbing the symbolism of Catholic ritual up against the performative camp of transvestitism. Marrying this video is a tableau of lifesize, naive papier mâché sculptures depicting Jesus and a host of cherubic angels, also by Ocaña. The papier mâché makes them appear warped, however, surrealist with their misshapen heads and lumpy bodies. Equally transgressive, and more overtly filthy, are Peruvian Sergio Zevallos’s black-and-white, almost devotional photographs, taken under the guise of Grupo Chaclacayo collective (1983–94). Again made during politically turbulent times (as Maoist guerrillas battled Peru’s military during the 1980s), Ambulantes, from the Suburbios series (1984), shows two androgynous lovers in a variety of abandoned spaces: a blowjob on a ruined balcony; a hand dexterously inserting objects into an anus among the rubble.

What are the things that don’t exist? The abstract, but dominant codes of life: nationality, religion, social class, cultural origin, the labels of sexuality and gender. Human constructs. The Bienal presents a multiplicity of voices from within these – so many that they jostle for one’s attention – voices that are either battling those constructs or battling on their behalf. Whether challenger or cheerleader, a cacophonous cry of injustice rises from almost all the works on show.

Like the wars, insurrections and tragic stories that mundanely flick across the news media, the Bienal begins to wash over me, desensitised as I am, in the epoch of rolling coverage, to the ambient horror of the world. Yet though individually the works lose some of their power amassed as they are, perhaps that is apt: this being, curatorially, a portrait of the powerless.

This article was first published in the December 2014 issue.