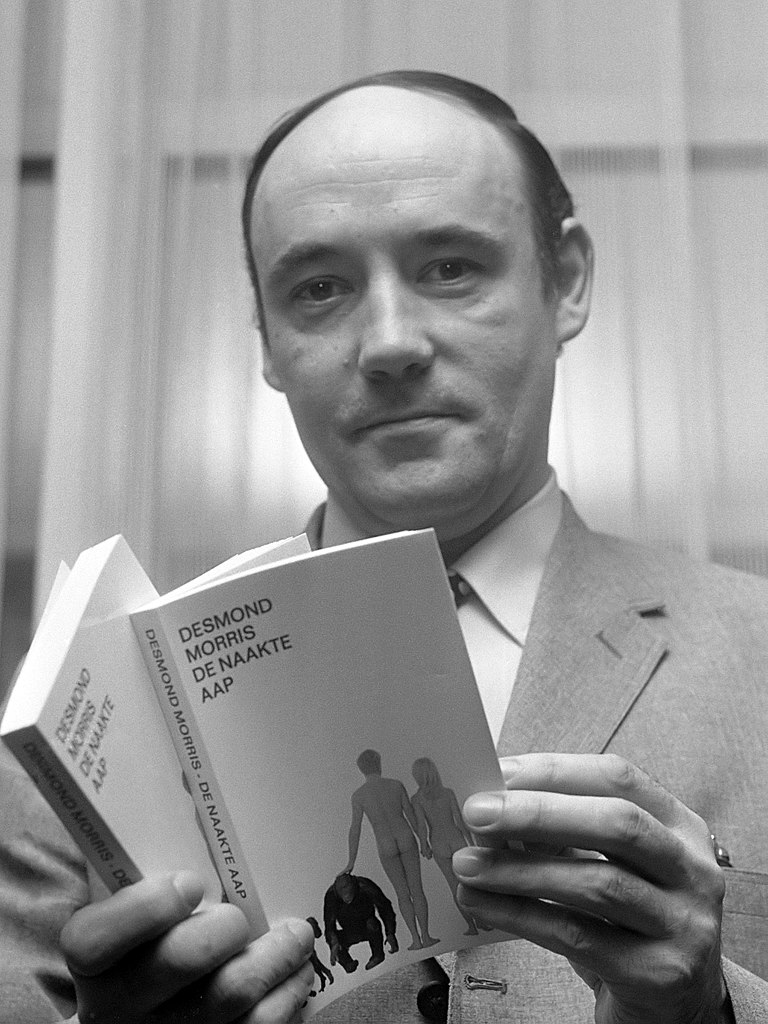

In 1967, London’s Institute of Contemporary Art (I.C.A) was preparing its move to new, larger premises in the Mall, appointing Desmond Morris as its new director. Morris was both an artist and a trained zoologist (he had been appointed curator of mammals at London Zoo in 1957), whose book The Naked Ape – a zoologist’s take on human behaviour – had been published that year. Fascinated by surrealism, evolution and creativity in animals and humans, Morris had staged Paintings by Chimpanzees, at the I.C.A., ten years earlier.

The Arts Review‘s Barrie Sturt-Penrose interviewed Morris on his plans for the I.C.A., and the idea of making it an ‘adult play centre’. Morris would only be at the I.C.A. for a year, resigning after The Naked Ape became a bestseller, and moving to Malta to write a sequel.

Barrie Sturt-Penrose You have just been appointed the new Director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Some people were no doubt amused, if not surprised, to hear that the Curator of Mammals at London Zoo had been made Director of the I.C.A.

Desmond Morris It’s not really so strange. I began in the arts and not in zoology at all. I was painting full-time, but when I came out of the army in the late 1940s the art schools were pretty dead. I was depressed by the thought of going to an art school and so I decided that as I’d always been interested in animals I would read zoology and to continue painting in my spare time. I studied at Birmingham University and then left to do post-graduate work at Oxford.

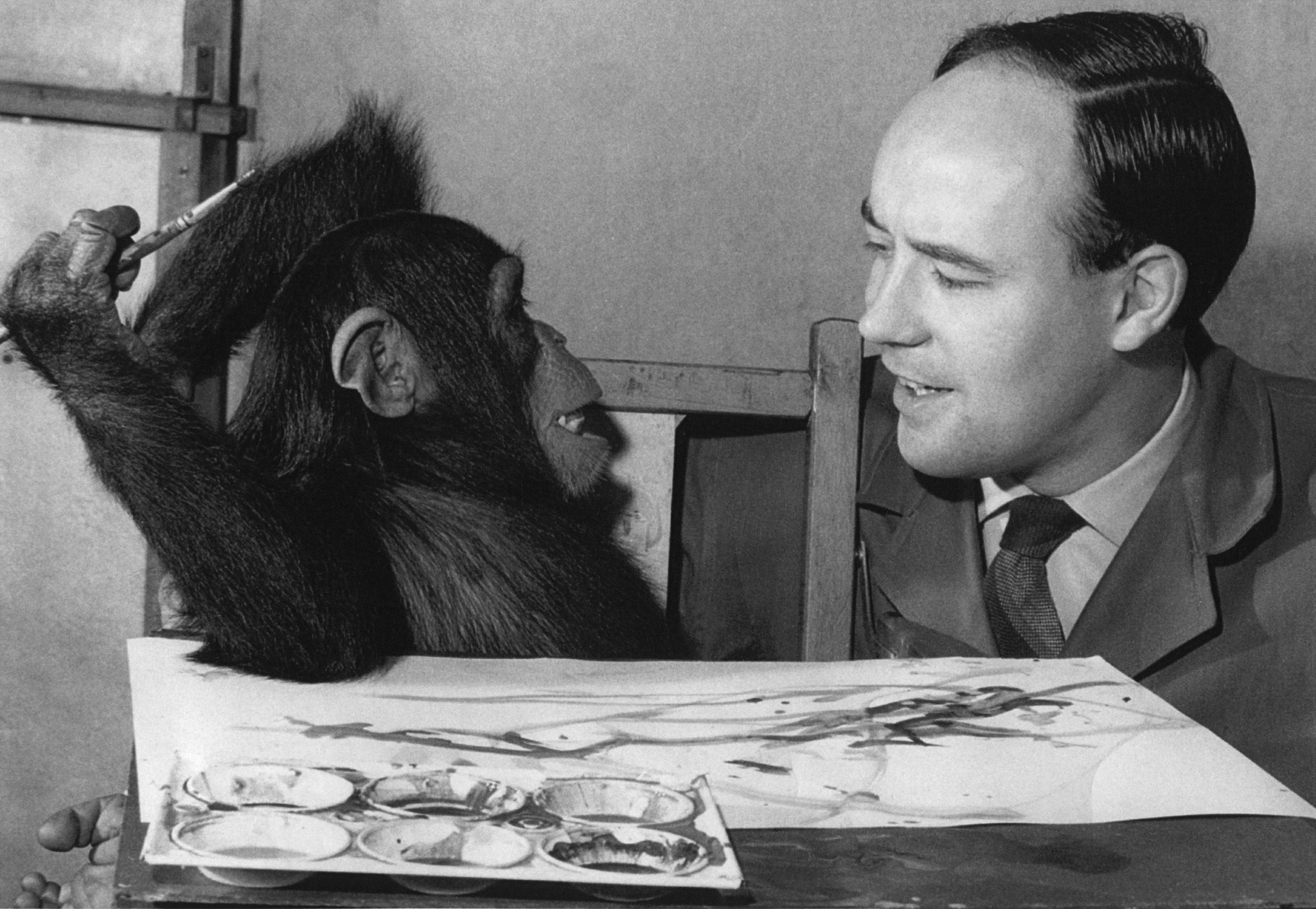

BSP I believe you had something to do with research into chimpanzees who could paint?

DM Quite by accident I came across a paper on the drawings of chimpanzees. It quite staggered me to learn that chimpanzees could produce pictures that were more than random abstract scribbles. Obviously one couldn’t use chimpanzees in a research unit at Oxford, but the idea stuck in my mind. Eventually we set up a TV unit at the London Zoo, that was in 1956, and we began research into animal behaviour and visual communications. You see, animals give mood signals which have evolved. If an animal wants to take off and fly it makes an intention signal like an athlete crouching before a sprint race. Eventually these intention signals become quite complicated and these signals become ritualised. People imagine that the colours, say, of birds are merely beautiful whereas, in fact, they are closely connected with visual communication.

BSP How was this research related to your work with chimpanzees ?

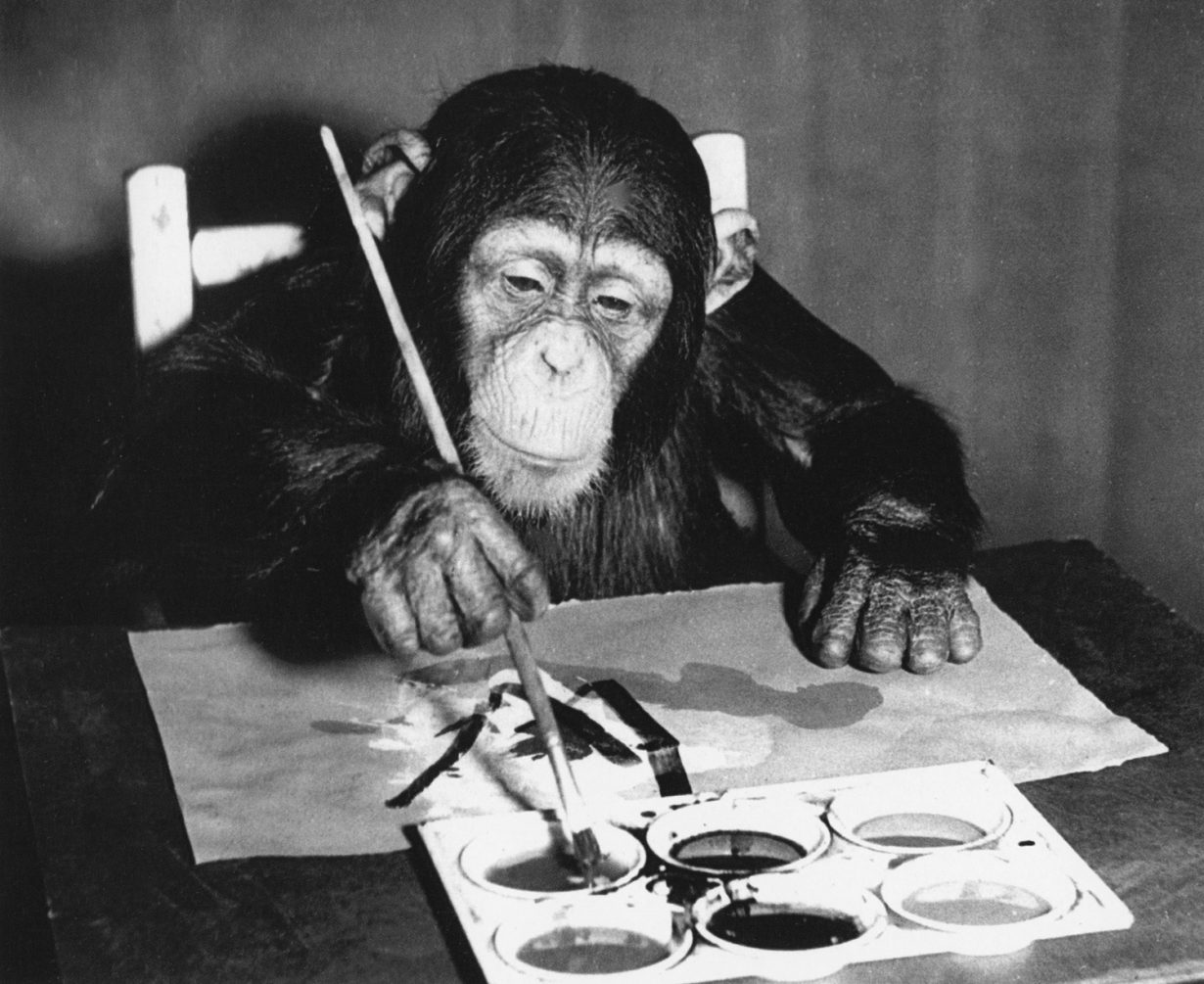

DM This experiment in America had shown that chimpanzees could be given paints and brushes and could produce pictures. This experiment led to my first connection with the I.C.A. because we held an exhibition of chimpanzees’ pictures. We were able to trace the early beginnings of the aesthetic impulse, clearly at a very low level. Unfortunately, some people made more out of our experiments than were in fact there. However, I could show that a chimpanzee could control compositions. He had a tendency to fill his compositions from left to right, a tendency to balance, a tendency to fill shapes on the page. Eventually Congo, a highly intelligent chimpanzee, showed that although his pictures were always abstract he did control to a certain extent what he did in his picture.

BSP This almost suggests that abstraction is in some way infantile.

DM Well, for a child, of course, it is. When a child makes lines and patterns on a piece of paper it is, at least at a young age, because he or she lacks the technical ability to represent something. Therefore, the very young child is preoccupied with purely aesthetic considerations. By the time a child is twelve or thirteen he is able to record outside events, and eventually this burden of recording becomes very heavy and the aesthetic factors are weakened. It was only when photography helped remove this burden that painting has returned to something of its original function. It is quite extraordinary how startled people still are with the various developments of modern art in this century. If they studied the development of picture making they would understand that the reverse process is now going on. Painting is now going back to the infantile condition – and I want to make quite clear that this is not a criticism – on the contrary this is the correct course for it to take. What has happened is that the art of the twentieth century has thrown off these chains of recording information. Painters are now virtually free to express what they like and how they like. Art should, I think, become more personalised.

BSP From our conversation I can now see your close connection with art and particularly experimental art. What will your policy be as the new Director of the I.C.A.?

DM What has always excited me about the I.C.A. is that it has promoted experimentation in the arts. It is an institute of experimental art. What interests me is seeing new developments as years pass. When the I.C.A. moves to its new expanded premises – after all it has been severely restricted for space – we will have a very large art gallery. It’s going to be possible to provide a platform for more experimental forms of art. And we can do this on a large scale. I really do think that experiment should be seen on a big scale in order that people can understand and see new statements and new trends in art. It’s very difficult for a new trend to be fully grasped in a restricted way. After all, when something is new it is difficult to assimilate straight away. As far as policy is concerned there is no need to change anything. When the I.C.A. was first thought of Sir Herbert Read said that it should be some kind of adult play centre – and he wasn’t talking in a theatrical way. He was thinking in terms of behaviour, of providing a place where adults could play and study the play of others. I was fascinated to hear – over 20 years ago – a man use this term play. Now I understand exactly what he meant. I think the I.C.A. has got to avoid becoming formalised. The Royal Academy was once the centre of experimental art and then it became formalised. At one time the Summer Exhibition showed the latest paintings to be seen in England, but eventually it became faithful to past years and not to the present or the future. The danger for somewhere like the I.C.A. is to put the brakes on new developments. It must keep itself open although there should be retrospective exhibitions especially when it ties in with present trends. There’s no harm in looking back as long as it has some present-day relevance.

BSP During the last few years more and more commercial galleries are showing experimental forms of art. Don’t you feel that the I.C.A. has, as a direct result, rather fallen into the shadows. In other words, the battles it fought for just after the war have now been largely won?

DM I think the new I.C.A. situation, that is to say, the Carlton House Project, can do two things. Firstly, none of the commercial galleries can mount shows on the scale we can do at our new premises. This is not just a matter of increased quantity. This is really the beginning of a new, larger impact. And, I hope, a deeper understanding of a trend. The other thing is that many of the exhibitions we hope to organise are of no real interest to the commercial galleries. I don’t think that competition really comes into this question at all. For example, an exhibition of chimpanzee pictures would be of very limited interest to a commercial gallery, but we could stage such a show. We are dealing in very specialised areas. In addition to this we are concerned with exhibitions which have definite themes. One exhibition we have lined up is to do with computer art and clearly this is not a show many commercial galleries could easily or willingly put on view to the general public. This doesn’t mean, however, that occasional one-man shows couldn’t be put on. For example, the Tate puts on the major retrospective one-man shows, but if we thought a major avant-garde painter or sculptor should have a retrospective show we would not hesitate to organise it. The I.C.A. should not have a rigid policy but should be there to provide a platform for any new trend which comes along. It should also be a centre of the different developments and to give them their first airing. Furthermore, the I.C.A. should also be a centre of the different arts and provide a common meeting house – designers will meet painters, sculptors, writers – and so on. It will become a nerve-centre for all these different disciplines. An intellectual bistro if you like!

First published in The Arts Review, vol. XVIII, no.25, December 1966

Congo the chimpanzee’s paintings were shown at Mayor Gallery, London, 3 – 19 December 2019. Desmond Morris will have an exhibition at Beaux Arts gallery, London, 14 October – 12 December 2020.