A group show in Kuala Lumpur brings together artists both historical and contemporary to paint a phantasmagoric portrait of the present

A dark-skinned man stands shirtless, smiling against a breaking dawn. He is pictured from the chest up; his facial features are round, and his eyes sincere, a stark contrast to the thin paint rendering the mountains in the background. To the left of the composition, a thorn fence is cut open. A labourer freed, the man looks us in the eye, hopeful for a new day. Al Manrique’s painterly vision of socialist-realist emancipation (Salubong Sa Bagong Umaga, or Welcoming a New Dawn, 1983) is contrasted with mmmmmmm… Manifesto (1965) by David Medalla. If Manrique charges dreams with a call to political action, Medalla’s textual manifesto captures the whimsy, affectation and expansiveness of such a project: ‘I dream of the day when, from the capitals of the world… I shall release missile-sculptures… on their way from our galaxy to the Spiral Nebula… Mmmmmmmmmmmmmm.’

These two works open Dream of the Day (taking its title from Medalla’s manifesto), curated by Patrick Flores. The exhibition centres, according to the exhibition text, ‘dreams, monsters, myths, hybrids, omens, spirits, and fantasies’ against the dual spectres of ‘colonialism and global mediatization’. Buoyant with possibility, it charts exciting trajectories for both art history and practice unencumbered by compensatory histories, a call to chart new conceptual ground without feeling the need to pedantically account for or replace colonialism and globalisation.

Dream of the Day features 39 artists from the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Myanmar and Malaysia, as well as artists located outside geopolitical Southeast Asia, from Sri Lanka and Egypt. While the exhibition includes artworks from across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the works are mostly categorised not by time, but by attitude. After Medalla and Manrique’s initial challenge, the remaining eight sections of the exhibition are in part historical, in that they provide a clear narrative across a period, and the rest contemporary, in that they each capture a mood, a sprawling, postmodern condition of contingency, speculation and phantasmagoria.

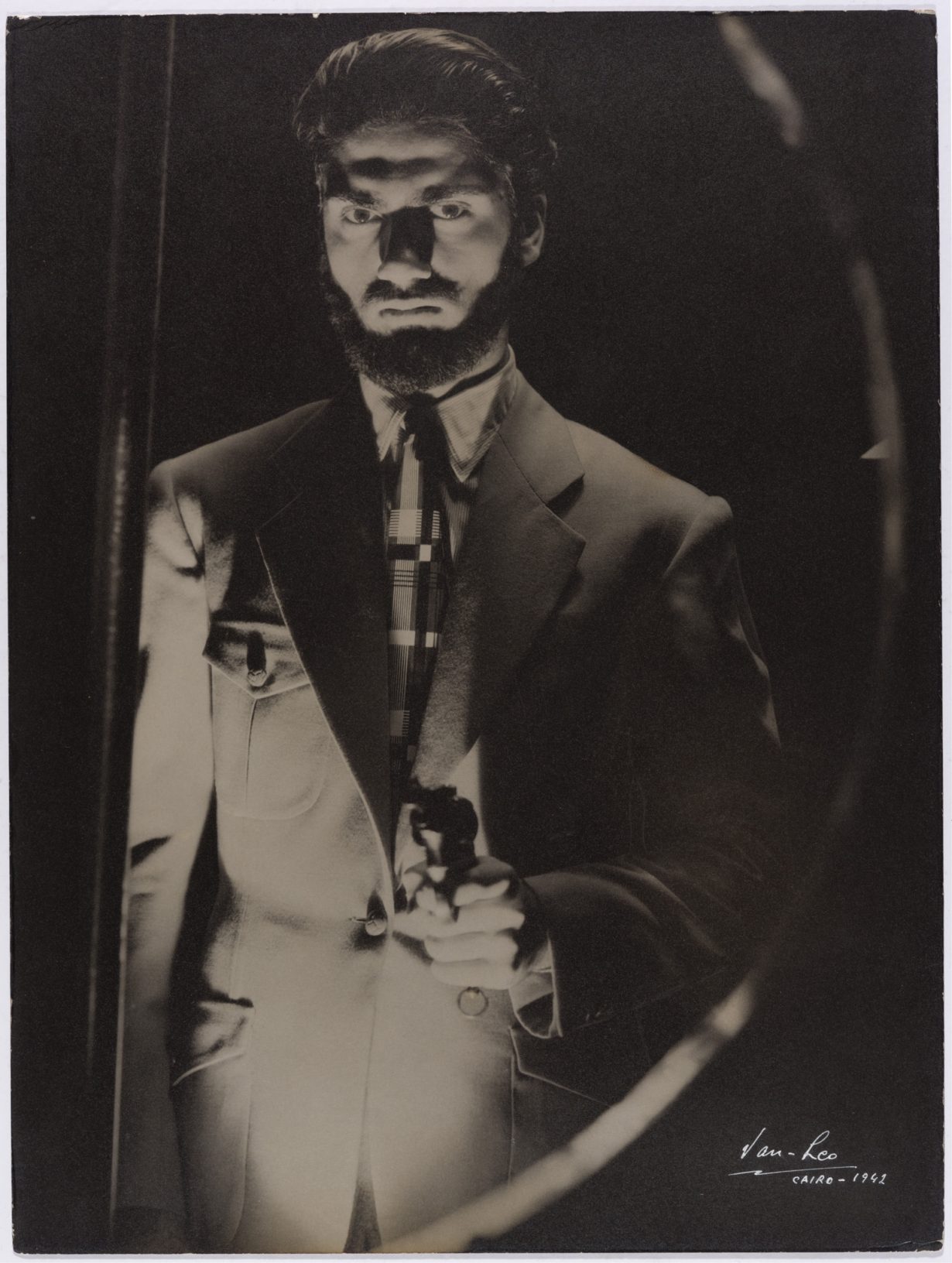

The art-historical sections are particularly strong, providing a nonlinear regional narrative for Surrealism. ‘Struggle of the Subject’ explores repressed subjectivities à la Freud, such as Van Leo’s haunting black-and-white self-portraits: in one, he wears a suit in front of a mirror, pointing a gun at both himself and the viewer. ‘Around Surrealism, Beyond Reality’ foregrounds fever dreams, rendering the ordinary unfamiliar: Ivan Sagita’s painting The Essence of Cow in the Macro and the Microcosmosis (1989) depicts the folds of skin on a cow as curtain-like portals in which feature smaller versions of these animals.

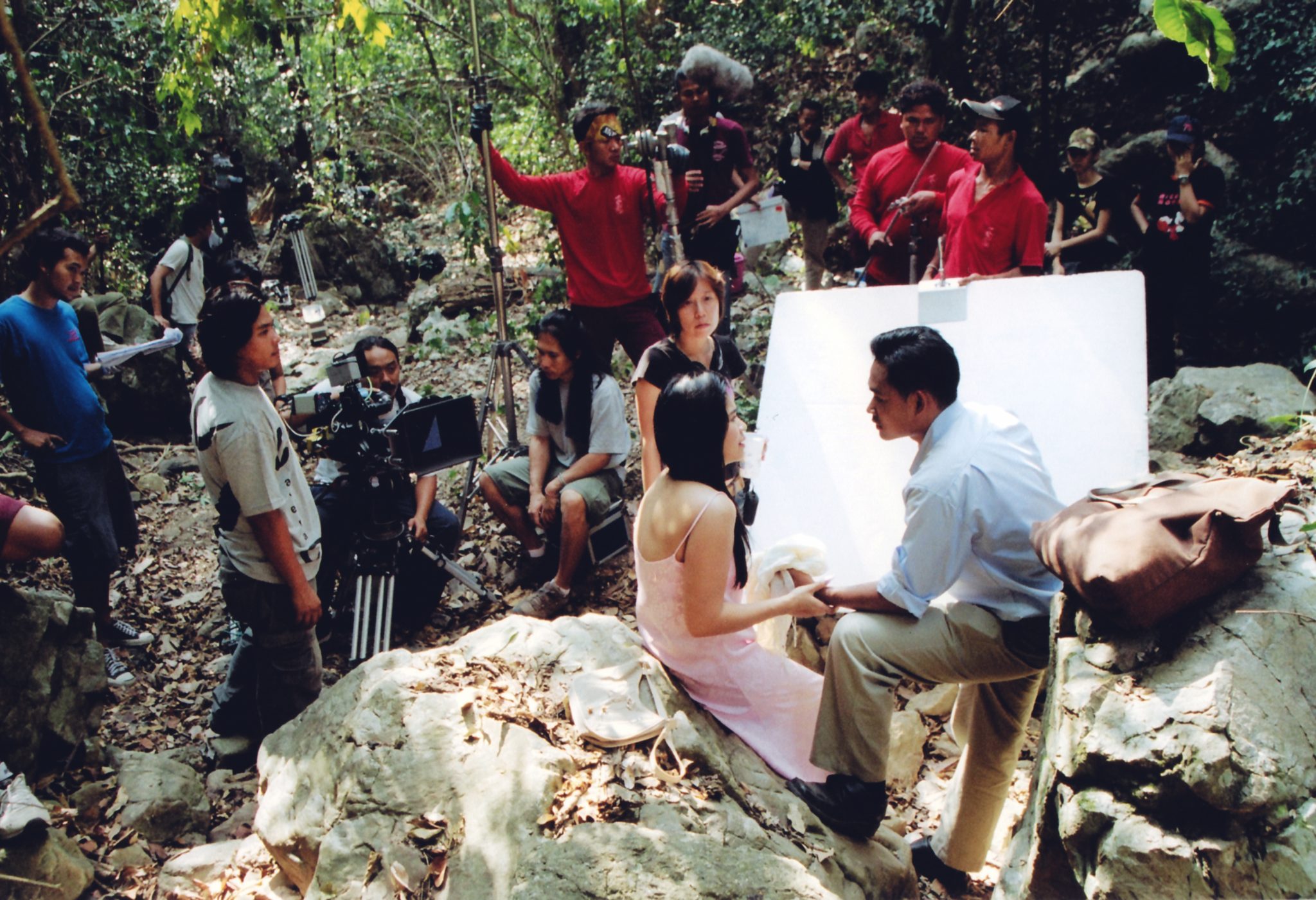

The rest of the exhibition presents a portfolio of imaginative trajectories. The strongest works each conjure specific visions for dreaming, from Club Ate’s dazzling queer retelling of Filipino mythology, to Veejay Villafranca’s 2011 photographic series of a psychic surgeon in Baguio City who operates with the dual faith of humoral theory and Catholicism. Nurrachmat Widyasena’s speculative work on Indonesia’s space agency imagines possible spacesuits and fictional emblems, and places a 3.5-metre tall propaganda poster atop a pile of rubble. Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Worldly Desires (2005), a meandering film-within-a-film, is interspersed with scenes of a bubblegum-pop girl group dancing in formation on a film set in a forest: “Does happiness still exist? Will I be as lucky as my mother is?” pleads the song they dance to, Nadia’s 2001 Will I Be Lucky? In the vast assemblage of this exhibition, though, certain works fall short. Kelvin Atmadibrata’s Self-Portrait (with acorns) (2012) – a series where the naked artist wears a string of acorns on his genitals and photographs both penis and acorn mid-thrust – has none of the artist’s signature queer camp and, occupying an entire room, felt like mere uncritical penile masculinity. These minor discordances do not detract from the project of the exhibition: it is daring, barely held at the seams, offering us no less than visions of how we might transform reality.

Dream of the Day at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, through 14 May