Maki Nishida visits a retrospective of the experimental multimedia Japanese group, but finds the absence of performers haunting

Founded by a group of friends at Kyoto City University of Arts in 1984, Dumb Type gained immediate critical acclaim for experimental live performances that melded digital design, music and performance. Many of its members past and present are influential artists in their own right, working in fields that range from the visual arts (Toru Koyamada, Tadasu Takamine, Shiro Takatani) to music (Toru Yamanaka and Ryoji Ikeda), to name a few. Teiji Furuhashi, an icon of 1980 and 90s media art, who died from an aids-related illness in 1995, was at the core of this nonhierarchical group’s formative first decade. This major retrospective, an expanded version of an exhibition hosted in 2018 at the Centre Pompidou-Metz, traces some 35 years of work and illustrates how epochal Dumb Type was, both in style and substance. The collective’s use of digital sound, electronic devices and industrial materials to create architectural installations is an aesthetic that can be seen in the work of a new crop of media-art protégés such as Rhizomatiks. Dumb Type’s subject matter – the ways in which society had become increasingly alienating, despite the promised benefits of new communication technologies, addressed in performances such as Pleasure Life (1988), or by the agonised strobe-lit bodies of dancers in s/n (1994) – also remains as relevant as ever.

Curated by Yuko Hasegawa, the exhibition is a ‘best of’ showcase, bringing together six largescale installations, most of which are performerless, reworked versions of early sets and edited documentary videos of key live productions. These include a version of 1989’s Playback, an installation based on the performance Pleasure Life, featuring 18 metal stands, each with a turntable that plays a record featuring original and new sound materials – among them early Dumb Type compositions, the greetings in 55 languages sent into outer space on Nasa’s 1977 space probe Voyager, and new field recordings. Particularly striking is lovers (1994/2001), a poetic and poignant solo work by Furuhashi, made just before his death. Video projections of naked men and women run across and vanish from the walls. Motion sensors that pick up the presence of visitors prompt the appearance of a ghostly figure – Furuhashi – who embraces the viewer before disappearing.

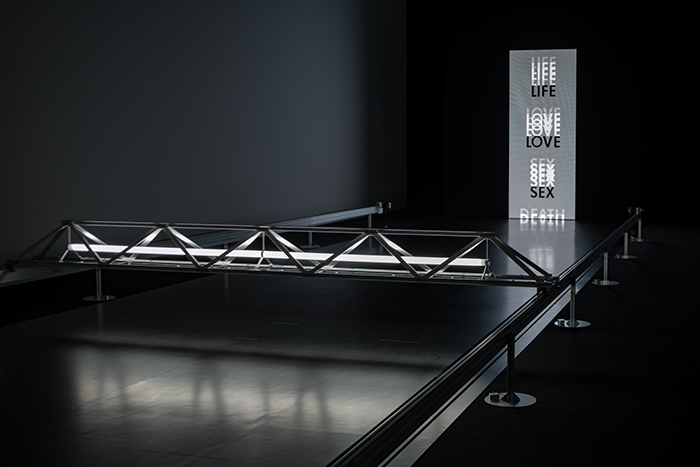

Given that most of the installations are recreations of historical live events, there is ample space for creative reconfiguration. For example, a 16m LED videowall combines scenes from Dumb Type’s last three performances, or (1997), memorandum (1999) and Voyage (2002), together with some newly shot materials. A concrete poem-like collage, the work transcends its nature as edited documentary footage. But other recomposed works are questionable. The final work of the show, for example, combines the 1994 video installation love / sex / death / money / life, now turned into a sleek LED videowall showing the words in large letters, with a reproduction of the stage set of pH (1990), comprising a truss bridge that is in constant motion, sweeping across the empty ‘performance area’. The resultant hybrid is visually strong yet conceptually puzzling – why combine two pieces from different phases from the group’s development? But it does raise important questions about the afterlife of live new-media performances: in what sense is there an ‘original’? And to what extent are modified versions or recut documentary recordings new works?

For all of Dumb Type’s cutting-edge technical sophistry, love and longing for human connection were key themes in the group’s first decade under the informal leadership of Furuhashi. After he died, its concerns seem to have shifted towards the creation of new technical and formal aesthetics. But this development is not well articulated in the exhibition, given its mix-and-match approach to re-presenting works that treat Dumb Type’s oeuvre as a series of interchangeable units. To get a fuller and more accurate sense of the group’s evolution, one is better off perusing the modest section of the exhibition that showcases archival materials and short videos of the original performances themselves.

Dumb Type, Actions + Reflections, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo 16 November – 16 February 2020

From the Spring 2020 issue of ArtReview Asia