Excavations and revelations in Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge

Brooding, stacked ingots of compacted soil, transmogrified by Claire Pentecost into an alternative form of currency, emit the slight scent of cocoa and camphor into a gallery space flecked with light from a beeswax-covered window. As part of her proposition for a different kind of value system, newly imagined banknotes depict not dead presidents but worms, bacteria and star intellectuals of contemporary ecology – Donna Haraway, for example – and her canine companion. Beginning with Pentecost’s soil-erg (2012) and continuing as a thread through the works in the group exhibition Symbionts, a contemporary eco-art discourse emerges along with the outlines of a recognisable aesthetic typology, one that sets out to recognise the critical partnerships and kinships between humans and nonhumans, and the labour of those often made invisible by biopolitical regimes (for example, human agricultural labourers and honeybees), and offers aesthetic propositions for a more ecologically minded future.

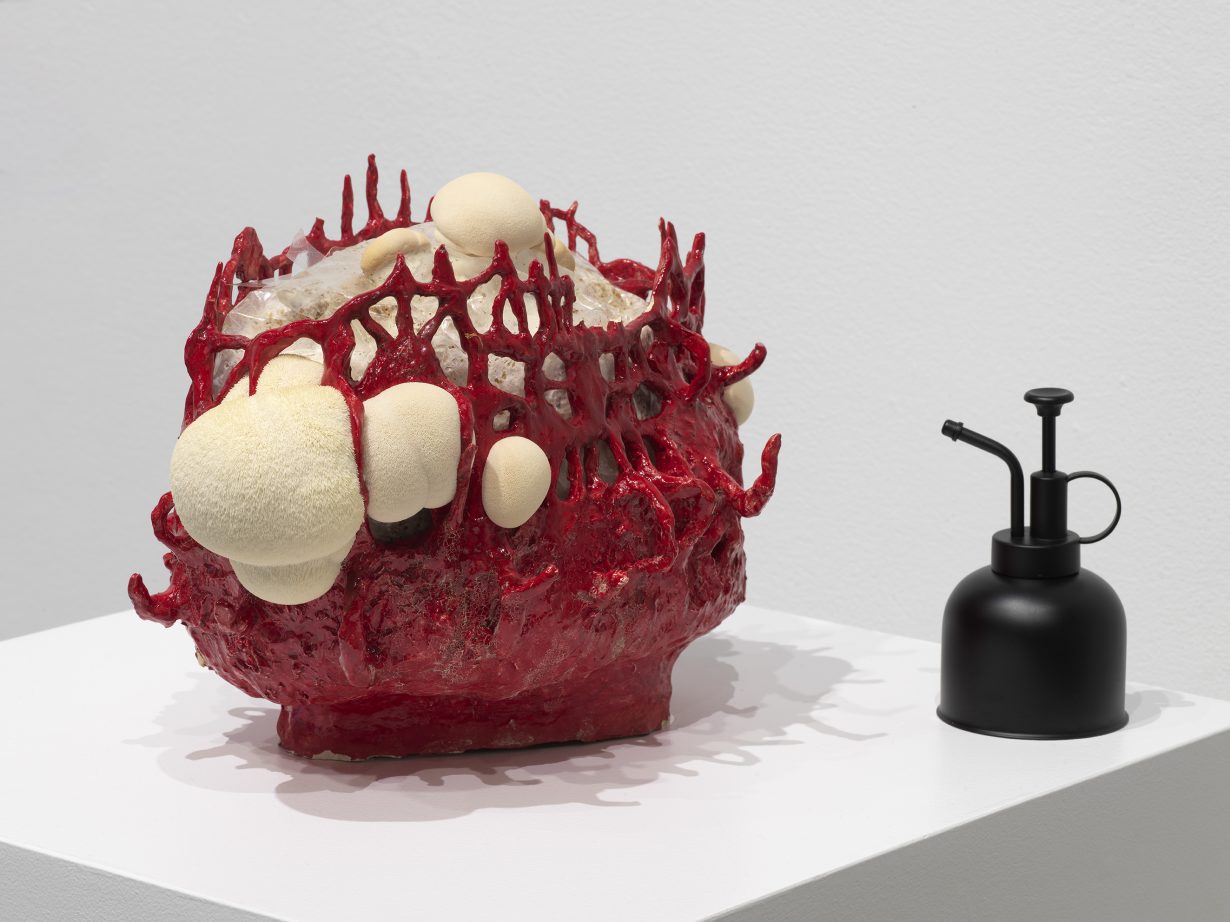

Revelations continue with Crystal Z. Campbell’s mixed-media installation Friends of Friends (Six Degrees of Separation) (2013–14), in which backlit bacteria slide ‘portraits’ of HeLA cells – the oldest human cell line still used in biological research today – appear to memorialise the biological legacy of Henrietta Lacks and her nonconsensual contribution to medical science, following the extraction of her cervical tissue containing these cells in 1951. Indeed, several of the artists’ interest in methods of museological display help to surface other kinds of invisible labour and human–nonhuman relationships: Candice Lin’s urine-nourished lion’s mane mushrooms are made with help of the gallery staff’s own urine, and Jenna Sutela’s sheets of Plexiglas containing luminescent labyrinths of slime mould hang in the dark, waiting to be activated by the illumination of flashlights, which are provided for the viewer.

the work, glass jar, lion’s mane mushrooms in substrate, plastic, brass sprayer.

Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles

In the darkness of the room adjacent to the main gallery, viewers are beckoned towards two videoworks by a melancholic chorus of howling wolves. Their cries are set to a score composed by White Mountain Apache composer Laura Ortman, which accompanies Wolf Nation (2018), Alan Michelson’s nature-cam-esque excerpt of purple pixelated, pacing wolves. Michelson’s video acknowledges kinships between the red wolf and the Lenape Munsee people (also known as the Wolf Clan), highlighting histories of species eradication and the violent displacement of people perpetrated by colonists – the nature-cam style of video recalling modes of surveillance. In the video on the parallel wall, biologist-turned-artist Špela Petrič looms silently over a bed of germinating cress, its growth inhibited in the places touched by her monolithic shadow. We are told that the effects of her prolonged vegetal encounter have changed her own physicality, as standing so long has led to fluid loss in her spinal discs; evidence that relationships between species are not always of mutual benefit, but mutual harm as well.

These excavations and revelations about our present conditions offer ecological speculations for more symbiotic futures. For example, Miriam Simun’s Interspecies Robot Sex (2022) presents a documentary-style inquiry into two divergent pollination biotechnologies, developed in the event of an absence of living bees: hand pollination and robotic bee substitutes. Though bleak, the image of hand-pollinators donning bee costumes while karaoke-style lyrics roll and the backing track to a Chinese love song swells in the background signals something uncanny, humorous and even touching about the joy of our most wholesome desires to cosplay as the nonhuman in the wake of our most extractive demands on a world scarred by ecological disaster.

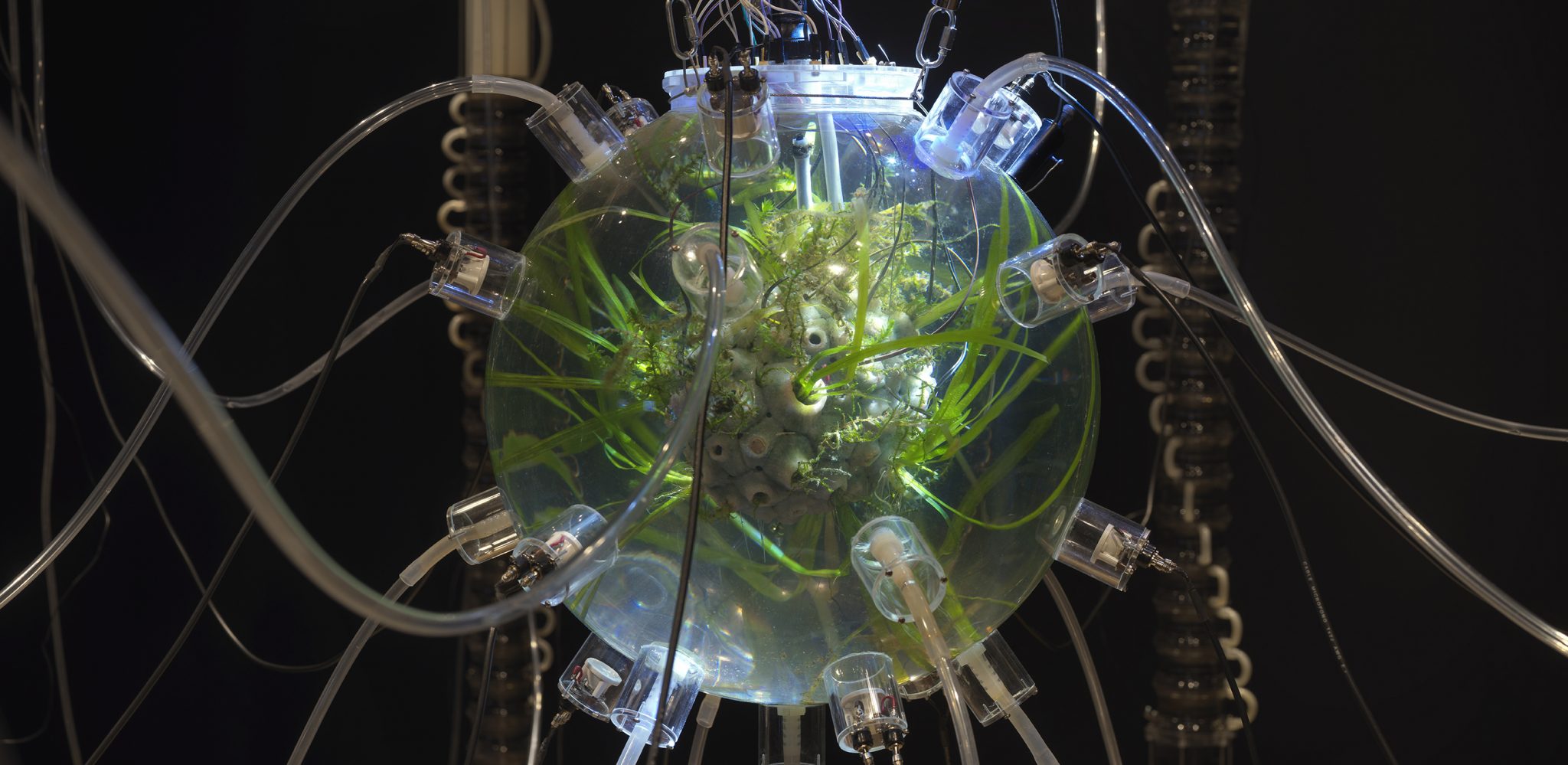

Symbionts’s survey of ‘bio-art’ since the early 2000s – a meander through biomorphic masses, vegetal growths and corporeal secretions, under a seemingly unified biological or ecological vernacular aesthetics – presents a question about its proclaimed turn away from artistic authorial control. While the skin of the exhibition is permeated by meditations on the role of nonhuman collaborators (spiders, fish, wolves, fungi and gut bacteria are credited or acknowledged to varying degrees throughout), these engagements ask a bigger question: to what degree do these nonhuman collaborators bear the burden of being symbols of human ideals about our relationships with them? The live fish and plants, for example, in Gilberto Esparza’s magnificent closed-loop bioremediation system, Plantas autofotosinthéticas (2013–14), is uncritically suspended, literally and figuratively, in the space of the art object.

In the exhibition, this question presses most in moments of ambivalence or refusal. In the adjacent gallery, we are warned of an encounter with Pierre Huyghe’s spiders while a sweet feline musk from Pamela Rosenkranz’s She Has No Mouth (2017) hangs diffuse in the air. The humble daddy longlegs, for whom visitors are invited to search throughout the room, were encouraged to build webs in the corners by being temporarily isolated by exhibition staff. Once they were set free, some spiders stayed and some left the building entirely, presumably to find a food source. Uncontained by the gallery, the spiders’ departure reminds us that while we ought to further reflect on our ideas of symbiosis (and symbionts), including how these ideas might become but new iterations of romantic ideals about nature, these crucial relationships between lifeforms exist, ultimately, outside of our control.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, through 26 February