An exhibition at Clearing, Brussels reveals the artist’s desire to dissect the rationalised psychopathy of Western civilisation

Eduardo Paolozzi was ambivalent about being referred to as a Pop artist, though he is often described as one of the ‘founding fathers’ of the movement in Britain. Like his peer Richard Hamilton, he emerged from the cerebral interdisciplinary milieu of the Independent Group, which sought to analyse and influence the future of art, design and technology. Perhaps correctly, the Scottish artist felt his affiliations with Pop led to reductive interpretations of his work and obscured its roots in an ideological approach. This show, featuring sculptures, suites of prints and an early animation (dating from 1963 to 1975), testifies to the complexity and formal cohesion of Paolozzi’s output. Paolozzi once described his work as a ‘health warning for an uncreative and thriftless society’, and much here implies that the relationship between man and machine is irrevocably tipping in a doomed direction.

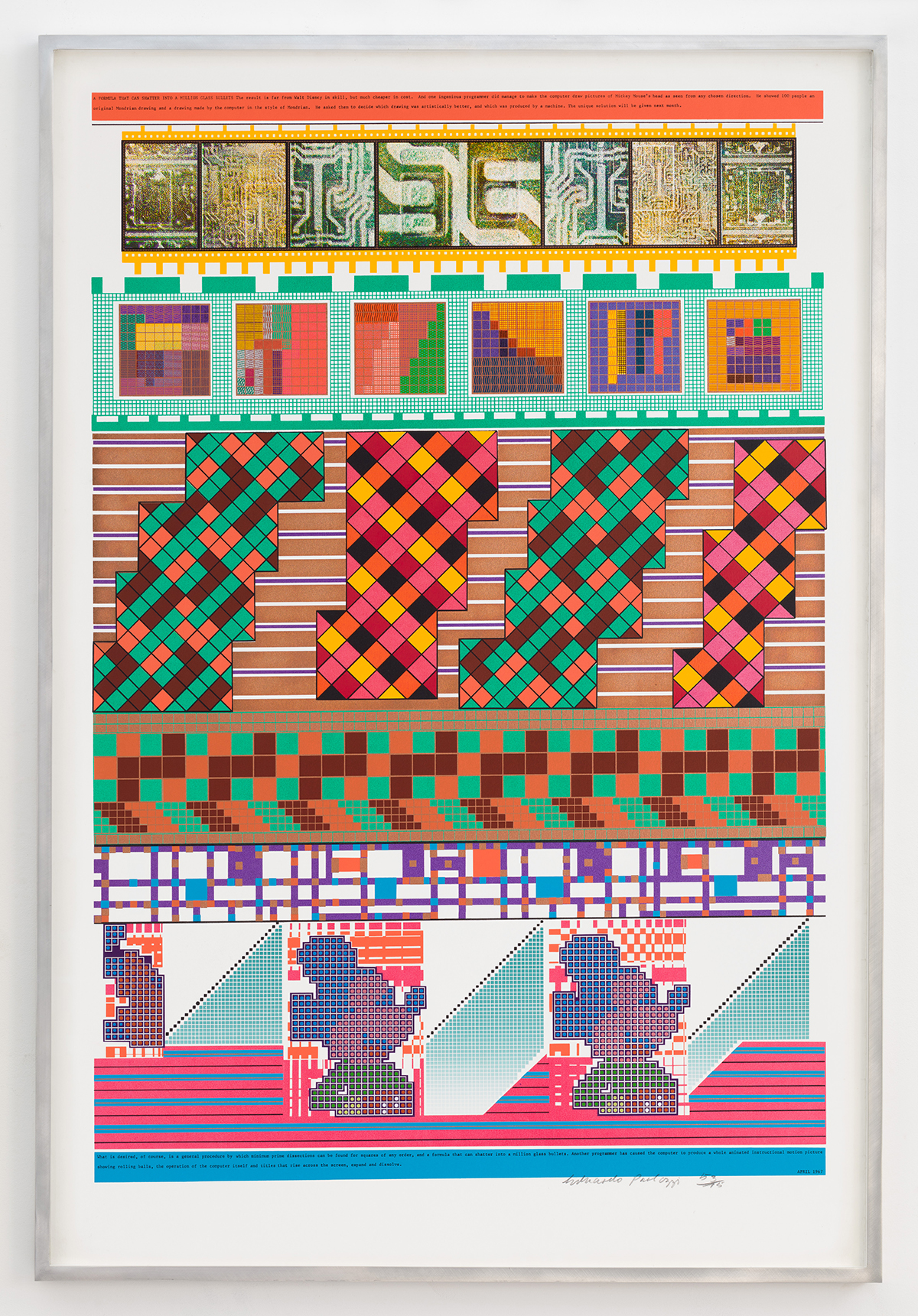

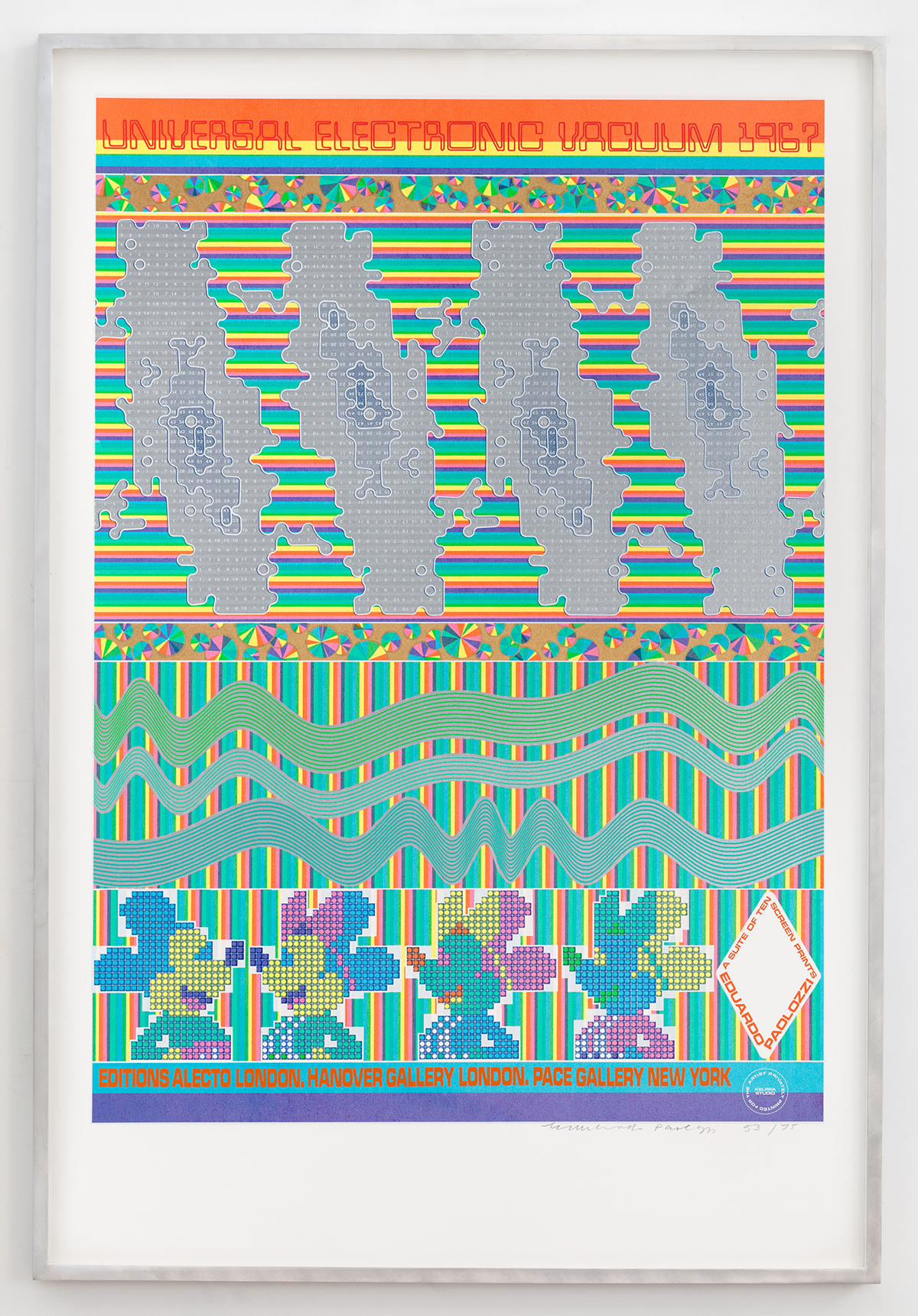

Attesting to his sociological interest in the apparatuses of commodity fetishism, it also reveals his desire to dissect and diagnose the rationalised psychopathy of Western civilisation. The series of screenprints entitled Universal Electronic Vacuum (1967) engages all the classic visual tropes of psychedelia: Day-Glo grids, Ben-Day dots, shimmering rasterized tracery. Its horror vacui is overwhelming, an overabundance of optical stimuli squeezed into every available inch. A comparatively sombre print from this series, War Games Revised, stands out: a schema of missiles and thermonuclear bombs rendered in matt silver and navy. These projectile weapons are arranged to resemble the components of an injection-moulded scale-model kit. The familiar aesthetics of mass-made playthings fused with the advanced instruments of industrialised killing, made while the Vietnam War raged, recalls the agitprop photomontage of John Heartfield.

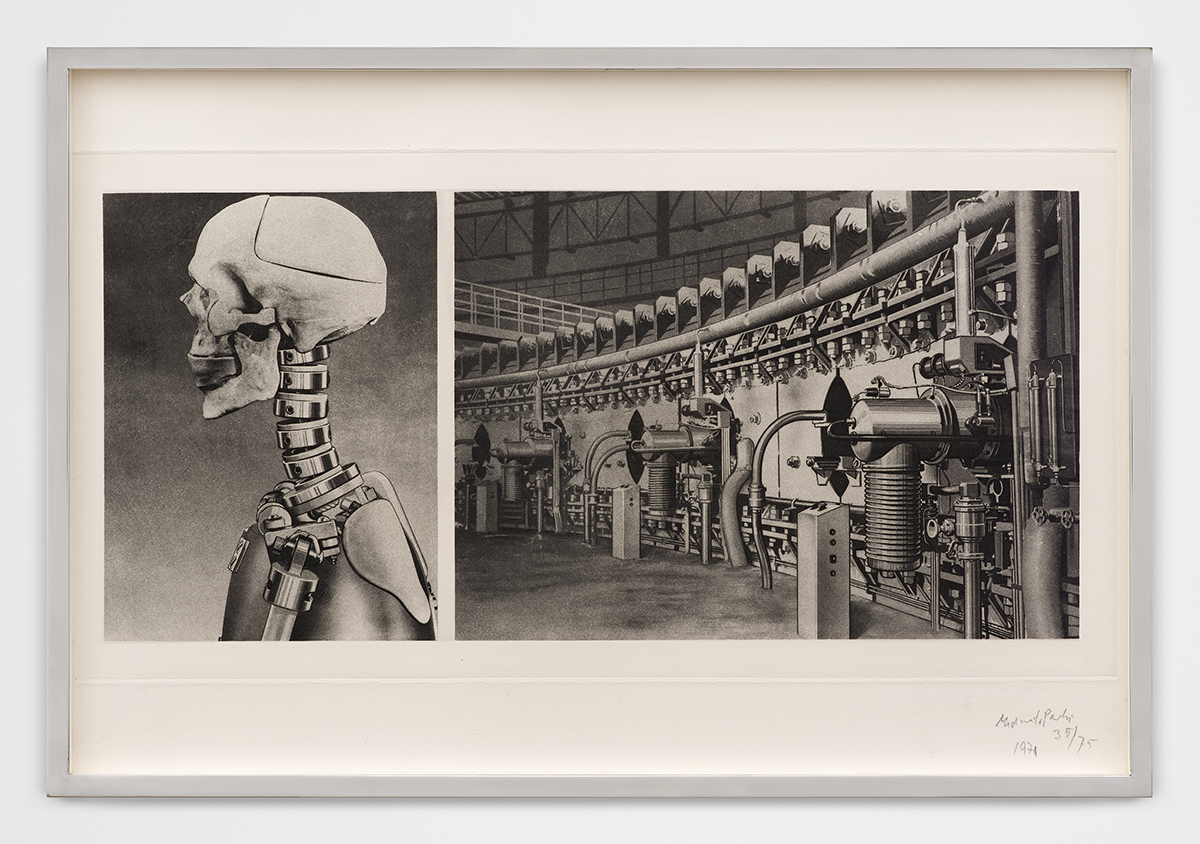

Another suite of prints, Conditional Probability Machine (1970), consists of 25 black-and-white etchings of sober, barely altered images sourced mainly from scientific and military journals depicting an array of subjects such as irradiated mice, crash-test dummies and cyborgian automata: a study of the ways in which twentieth-century scientific and technological achievements were driving the human species towards more efficient forms of barbarism. Clearly, Paolozzi was deeply preoccupied with the psychological and physical impact of technology; yet while he may have had some inkling of a dystopian future, he never could have envisaged the techno-rational containment of our cybercapitalist twenty-first century. Paolozzi’s vision is positively rose-tinted when compared to the bleakness of our current situation, more Barbarella than Black Mirror.

The show’s nucleus is a metallic citadel of mechanomorphic sculptures, amalgamations of mechanical miscellanea: household appliances, turbines, pistons and industrial tubing prefabricated in monochrome cast metal. Parrot (1964) appears like a priapic totem from some postapocalyptic world; Pan Am (1966), a welded modular construction, resembles the debris from a spacecraft that broke apart on reentry. Several of these were originally commissioned for a playground, reflecting the enthusiasm of those booming years in which factions of artists believed that art and architecture could be democratising, emancipatory agents for fomenting positive social change.

The show’s title is taken from an artist book, a manifesto-cum-monograph Paolozzi produced in 1964, its focus the changing dynamic between humans and machines. Yet from today’s vantage point the titular phrase might also be seen as referring to the way in which the utopian initiatives and progressive aims of the 1960s were moribund and ossified by the century’s end. Ultimately, The Metallization of a Dream constitutes the remnants of a once-vital avant-garde that, like Russian Constructivism, was unironically committed to an idealistic position. Instilled in these works from Paolozzi’s zenith are the imagined possibilities of a long-lost moment – assured exuberances all but absent from our plague-ridden present.

Eduardo Paolozzi: The Metallization of a Dream, was on view at Clearing, Brussels, 17 January – 14 March 2020.