Memory and migration drive the Berlin-based Nigerian’s experiments in shared sensory abundance, which highlight the artworld’s conservatism along the way

I first encountered Emeka Ogboh’s art in 2017, at Skulptur Projekte Münster, in a grimy underground passageway adjoining the city’s train station. At his chosen site, a favoured spot for buskers, the Nigerian artist presented Passage through Moondog (2017): an audio collage of words and music by the beloved Viking-helmeted US street musician/composer/poet, who moved to Germany late in life and died in Münster in 1999. The ‘passage’ of the title implied geographic transits that carry music with them, vicariously transporting listeners in turn. At various venues nearby, Ogboh also offered a consumable artwork: Quiet Storm, a heady honey beer overseen by a local master-brewer, infused with lime-blossom grown in Münster and ‘sonified’, as he put it, in a Belgian brewery during fermenting by proximal speakers playing soundscapes from the loud megacity of Lagos. (‘Very good,’ said one expert, in a review which also noted that adding honey broke a purity law of German brewing.)

A few years later, in 2021, I’d wander my Berlin neighbourhood while feeling it similarly overlaid with metropolitan Nigeria, listening to Ogboh’s sophomore album, Beyond the Yellow Haze (2020) – pistoning dub techno enveloped in swirling field recordings of Lagos bus drivers rapping their routes, street hawkers musically plying wares. Urban melee as pulse, as palimpsest, as collectively composed and daily rewritten city-symphony. That same summer I watched the artist, who’d moved to Berlin in 2014 for a daad residency and decided to stay, play a rapturously percussive Afrobeat-flavoured DJ set at another travel-associated site, on the concourse of the just-decommissioned Berlin Tegel Airport. In 2022, visiting his installation Ámà: The Gathering Place (2019/21) at the city’s Gropius Bau, I sat under a nine-metre-high sculptural tree wrapped in orange and green fabrics patterned by Nigerian graphic designers (Ogboh himself is one by training). The institution’s soaring atrium was now an ersatz village square, typically an agora for eating and drinking, social exchange, debate, the virtues of sociality; and here it was graced by a 12-channel audiowork playing folksongs specific to Igbo people from southeast Nigeria, where Ogboh was born in 1977. Meanwhile, to add to Quiet Storm and its predecessor libation, the poky stout Sufferhead original (2016) – inspired by Afrobeat kingpin Fela Kuti, based on a taste survey of African migrants in Berlin and developed with a Wedding brewery – there was a new, locally brewed ‘conceptual craft beer’, Ámà, to sample.

What connected these works was, on the one hand, their interest in intersecting one place and another; validation of public space’s multi-form uses; and exploration of how memory, tradition and a sense of place are encoded, carried down migratory routes, sustained in sharable cultural products. But it’s also notable that, within the visually oriented economy of contemporary art, they all skew towards an intensely multisensory approach. Sound’s extraordinary articulacy, particularly – what it can convey, where it can put you, what connections it forges and preserves – was Ogboh’s starting point in 2008, when he attended a galvanising workshop in Tunis, Egypt, where Austrian multimedia artist Harald Scherz discussed the audible spectrum. Shortly after, back in Lagos and phoning a friend, Ogboh was surprised to have his location identified by the background ambience; since then, beginning with the sequence of audioworks Lagos Soundscapes (2008–), which emphasise the city’s rhythmic heartbeat as it’s built by speech and noise in public space, he has progressively gone all-in on the extravisual sensorium.

“Typically, it’s challenging to incorporate all five senses into a single artwork or project, but I constantly try to include as many as possible,” says Ogboh via email (though we live in the same city he is, as often, on the move). “It elevates artworks beyond mere visual displays, and there’s a heightened engagement that promotes emotional connections, deeper understanding, triggers memories. You can convey meaning and narrative with greater nuance. The nonvisual world speaks a different language, it resonates with our emotions and bypasses sight’s limitations. Plus, a multisensory approach enhances accessibility, ensuring that a wider audience, including individuals with disabilities or sensory differences, can engage too.”

Aside from their inclusivity, Ogboh’s manoeuvres might illuminate the conservatism of the artworld. (Relatedly, perhaps, he didn’t deign to work with a gallerist until 2020, when he joined the select, bijou roster at Paris’s Galerie Imane Farès.) But his primary intent appears to be to reach substantial publics in a meaningful way, one partly influenced by the relational aesthetics of the 1990s but differing from it in its determined and strategic politics. Ogboh’s core concerns are migration and associated questions of identity, national identity, belonging – and he literally makes them sing. At the 2015 Venice Biennale, for instance, amid the European refugee crisis, he presented the audio installation The Song of the Germans: a ten-channel audio work that replayed the German national anthem as sung in ten different African languages by African expats living in Germany. In 2021, for the Edinburgh Art Festival, the related Song of the Union featured Scotland-based singers from the EU’s 27 member states singing Auld Lang Syne.

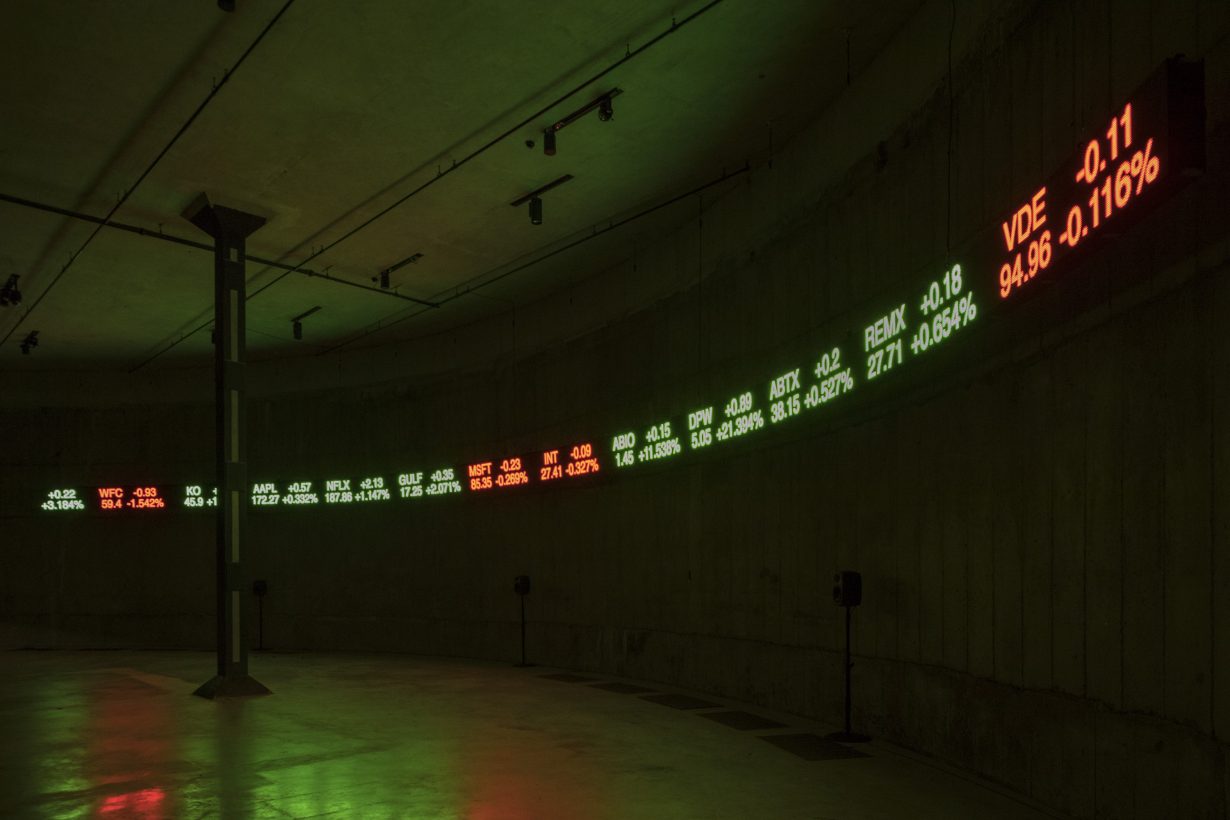

At the Athens half of Documenta 14 in 2017, Ogboh had shown The Way Earthly Things Are Going, a work that, tracking back to the Greek financial crisis of 2007–08, mixed a multicoloured feed of live numbers from global stock exchanges with a sung lament, When I forget, I’m glad, by a Greek women’s vocal group. It linked the near-abstraction of stocks and shares to real-world effects, not least economic migrancy, the song’s title suggesting both a momentary salve and the ease with which a nonmigrant might disregard the vicissitudes shaping others’ lives. One apparent aim of Ogboh’s emphasis on communal making, from consulting with drinks-makers to marshalling choirs to creating sociable environments, is to bridge such gaps. “Migration”, he notes, “is a concept inherently rooted in communal experiences. It transcends individual narratives, encompassing shared journeys, struggles and aspirations – in this context, fostering connections and shared activities through collective activities becomes not only important but integral to the essence of my work. I try to celebrate the richness of collective creativity, promote a sense of belonging and solidarity, the interconnectedness of human experiences, the power of collective action.”

Food and music are universals. They’re also, while being sociably communal, potential empathetic bridges in a way that visual images alone are not. For some, eating the food of migrants or dancing to variations on their music is the only time that these people or the circumstances that uprooted them even begins to enter their consciousness. Ogboh, in, as he says, “inviting audiences to partake in sensory indulgence, immediate pleasure, bodily engagement”, supplies the bridge; in framing that pleasure conceptually in his exhibitions and the literature around them, as if offering tasting or listening notes for the unskilled, he also insistently connects it to people, makers, peoples, collective makers. It’s notable that another means of strategic connectivity he pursues is to flip or creolise superficially Anglo-European forms. We all know, and can hum along to, the melodies of national anthems or Auld Lang Syne. In musicalising the streets of Lagos, Ogboh’s soundscapes involve a conception of sound as music that links back to American experimental composers – John Cage, inevitably, but also Pauline Oliveros’s related notion of ‘deep listening’ – while the idea of a city’s accidental, collective music connects, neatly, to the early modernism of Walter Ruttmann’s 1927 film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City. The inexorable rhythms on Ogboh’s albums, while approximately familiar to dance-music listeners, seemingly show their African roots all the better for being surrounded by Nigerian voices.

Ogboh has previously noted how different Berlin is to Lagos; when he first moved there, he said, he couldn’t sleep because it was too quiet, and added that he found it trickier to read this city through its sounds. Instead, the artist who this year added spirits to his menu – Boats (2024), at the summer festival of Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art, featured a gin pointedly made with both Nigerian and Tasmanian botanicals, and referenced Australian rightwinger Tony Abbott’s 2013 anti-immigrant ‘stop the boats’ campaign – appears to be finding another route: through the stomach. “Gastronomy has emerged as a significant source of inspiration for me,” says Ogboh. “In recent years Berlin has become a culinary hub, offering a range of tastes and flavours that allow one to travel the globe. It’s increasingly captured my attention and motivated me to start working on an idea centred around the culinary landscape.” And with that he signs off and goes back to prepping a remix of his most recent album, 2022’s 6°30’33.372”N 3°22’0.66”E, named for a precise location in Lagos. “I have,” says Ogboh, “a lot on my plate right now.”