The founder of Forensic Architecture on the power of hyperaestheticisation, digital violence and how to read the world around us

The Israeli-born architect is the principal of Forensic Architecture, a collective of architects, artists, academics, lawyers and journalists founded in 2010 and based at Goldsmiths University, London. Working with various partner organisations, the group conducts investigations into alleged human rights abuses by nation-states, security services, police and corporations. Often used in legal actions and public enquiries, the work is also presented online and in museums and art centres internationally. This year Forensic Architecture was the subject of solo shows at the ICA, London, and the Whitworth, Manchester, and participated in the Venice Architecture Biennale. Investigative Aesthetics, coauthored with Matthew Fuller, was published by Verso in August 2021.

ArtReview Your new book involves a reassessment of the term ‘aesthetics’. I wonder if you could explain that a little in relation to Forensic Architecture’s work.

Eyal Weizman For us aesthetics is not a way into art and culture, but a fundamental principle of our work. Aesthetics is perceived as pleasurable. It is synonymous with beauty and decoration, with play or a lack of seriousness. Where subjectivity is required of the artist or scientist, the investigator must be objective. Our work starts by trying to break that dichotomy. We are saying, to be effective in the forensics field – in journalism and law, within human rights – the nineteenth-century epistemic virtue of neutrality is unhelpful. And though we will not compromise our ferocious engagement in the verification of the facts, a researcher must in fact be embedded, situated and perspectival to the issue they are dealing with. The way you achieve that is through the field of aesthetics. Aesthetics is not a question of beautification but of the sensible.

AR So what is aesthetics to Forensic Architecture?

EW Aesthetics is effectively the way in which things register the proximity of other things. Deep attunement to objects and surfaces is our starting point. We look with care and detail at surfaces, whether they are digital surfaces or material, such as the first few millimetres of an architectural surface. Paint on plaster is like a membrane that registers the building’s being in the world: the temperature, pollution, differences in radiation. Through the very first surface millimetre of a building you can read changes in climate and emissions, or even changes in environmental laws or a political situation. Just as we are attuned to a close reading of texts, we can be attuned to the close readings of material surfaces, of organic surfaces.

AR What is ‘hyperaestheticisation’, then – another term you use?

EW If aesthetics is the relationship between bodies and objects in the world, then to hyperaestheticise becomes an ethical-political act in which you examine, at a particular historical conjunction, the way in which, say, a landscape, has become aestheticised to a particular action upon it, radiation exposure, for example. The way you do that is to increase the object’s sensorial ability by networking the object or landscape with other local sensors. What is fabulous is when you aestheticise a piece of territory.

We’ve done that recently in Louisiana for a project that was coordinated by the artist Imani Jacqueline Brown. We took a sugarcane field and looked at aerial images and at the surface terrain in search of graves of formerly enslaved people. We become attuned to the minutiae within the terrain. After the crop is cut we can see every small angulation in the territory, we can see moments where the topography does not correspond to the natural way in which water would sculpt the slope. We can deduce that there must be something under the terrain. Sometimes the plants that grow over graves are slightly different from the plants that grow around them. These are ways in which the organic surface and the topographic surface are hyperaestheticised.

Then you go into books and you go into the archival records; sometimes you go into photographic records and look at the threshold of detectability, at the very minutiae of the film to see if there are any other traces or anomalies to be registered. By putting all this together, by hyperaestheticising testimony, media surfaces, material surfaces, organic surfaces, you create an assemblage of sensors. That is where the ethical-political act occurs. Then of course there’s the act of construction, which is what happens in our studios.

AR You chose to call it a studio rather than a lab?

EW Absolutely: a lab is all about hermetic protocol, closed-door experimentation. You reduce the friction between your work and the world outside. A lab works with distilled evidence; we work with what we call dirty evidence. Just think about a gun being pulled out of the ground, it’s full of dirt. For the legal process, you need to clean off the dirt and present it. For us, we’ll be interested in what kind of ground it was on, how can we actually take the dirt to open up new lines of inquiry, to make new claims, to criticise the linearity of the legal process, which is often used against those people most in need of protection. We also work experimentally in an open-studio manner with a multiplicity of collaborators. It includes people who are within a given struggle themselves. That’s very different from any other forensic investigators, but for us it’s absolutely essential that the evidence becomes a tool for those social movements or those people who are at the forefront of the struggle against state repression.

AR Why show the work in galleries then?

EW If you want to politicise, if you want to create a wider reception, if you want to work towards political change, you need to put it in other fora, like the media. For us, art and cultural spaces have been very good venues in which to get our work beyond the legal bubble.

AR The gallery can be a problematic space, though. The idea that it is a hermetic space – a clean white cube, where art is shown without being muddied by the outside world – is repeatedly shown to be false. When you were invited to take part in the Whitney Biennial, you produced an investigation into Warren B. Kanders, vice chair of the board of the institution’s trustees and CEO of Safariland, which is one of the world’s major manufacturers of so-called less-lethal munitions. This year you threatened to close a solo show at the Whitworth, in Manchester, after it removed a message of solidarity with Palestine.

EW My very first book, A Civilian Occupation [2003], written before Forensic Architecture [FA] was formed, started as an exhibition catalogue, but the exhibition got banned by the Israeli Association of Architects. After FA was founded, art spaces offered us two things: money – always good – and a space that allowed us to say things that are impossible to say in court. A court is a much more restricted arena: any form of political statement is not only frowned upon; you’ll be thrown out.

Of course, we came to realise that though a gallery is a place that can be used to reflect upon politics, it is not a place outside of politics. Our experience at the Whitney illustrates that there’s no safe ground. All the forums in which we work, whether they are journalistic, judicial, parliamentarian, the UN, they’re all skewed in different ways. That’s why we need a presence in all of them. You need to both fight with them or through them, and to fight them sometimes.

When we were nominated for the Turner Prize in 2019, UK lawyers for Israel, who were one of the organisations leading the campaign against us in Manchester, immediately complained that we were falsifying the case against Israel, and that the Tate should not show these anti-Israeli activists [the collective showed an investigation into the 2017 police raid of Umm al-Hiran, a Bedouin village in the Negev desert, which left two civilians dead]. They lost that time and they lost in Manchester. Two-nil. The Israeli government ended up having to recant their version of events, however, admitting that our investigation was correct, that the person was killed, that he was not a terrorist.

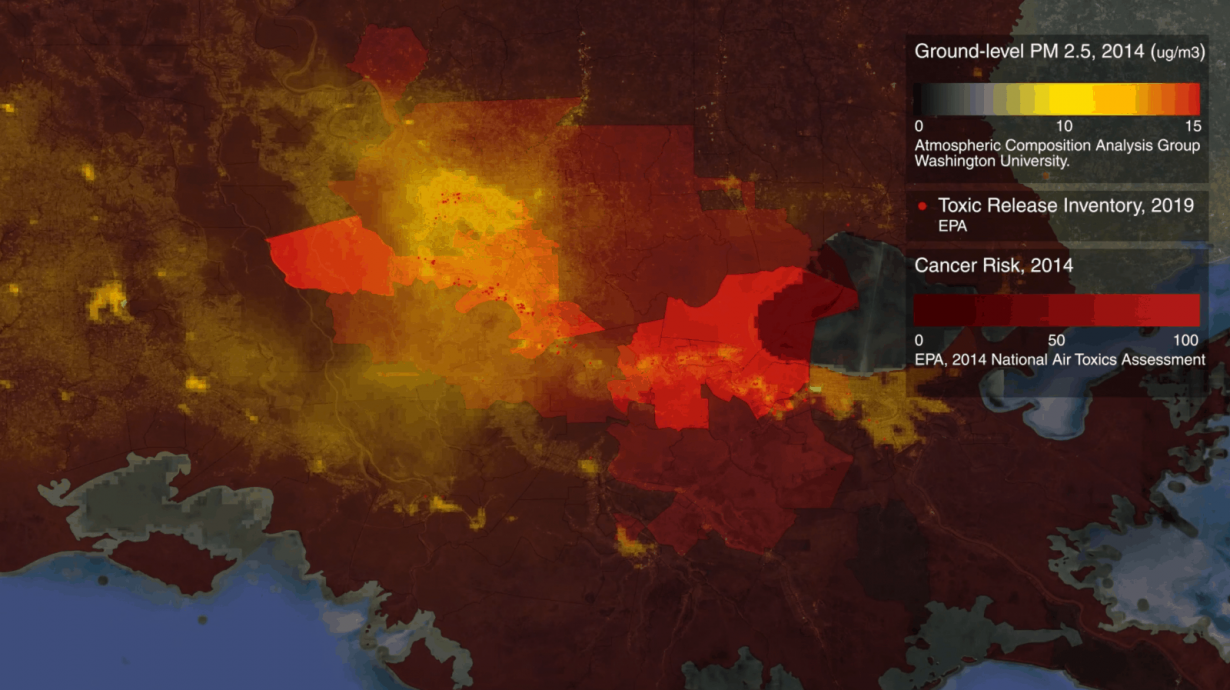

AR Your Louisiana investigation starts off with a memorial to the leader of the Confederacy – a symbol of racism – in Louisiana, but that work’s real subject is another form of structural racism, air pollution. The latter receives a fraction of the attention the so-called statue wars do.

EW Kinetic violence is something that registers in the media, yet when you come to environmental violence, ‘slow violence’, as Rob Nixon calls it, it becomes less visible. The changes are sometimes accretional and imperceptible, and you need to try to find other strategies to aestheticise things that don’t lend themselves to aesthetic capture in the same way. In that project in Louisiana with Imani, we asked ourselves how you defetishise that which oppresses you. Even oppression tends to have names, figures, sculptures, buildings that represent it. The crime scene in Louisiana is immense in space and time. I think that this is one of the great challenges for us.

AR After kinetic violence and environmental violence, the third violence is what you have termed digital violence.

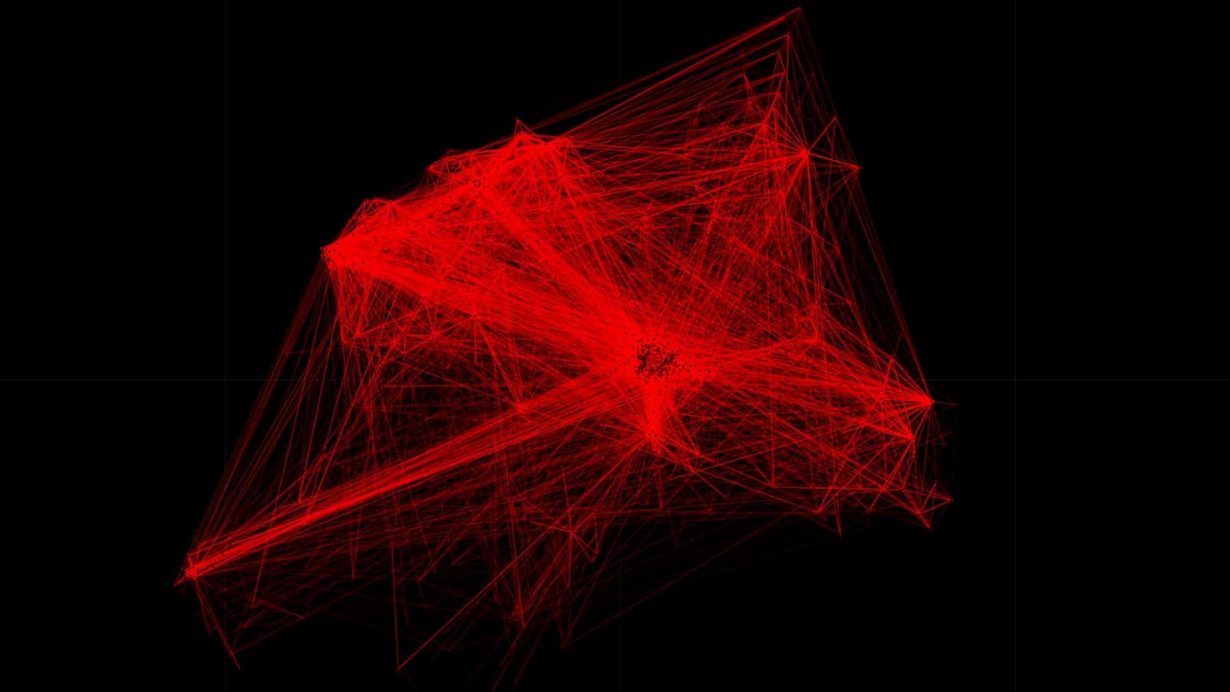

EW We were part of a big coalition of organisations that were researching the cyber warfare company NSO Group. Effectively what we’ve done on cyber surveillance is to look at the people who were targeted. What happened to their lives? What happened to their mental health? How does digital violence enable violence in the physical domain? What resistance is being offered? For us, we don’t want to separate the environmental, digital and kinetic violence but show how they overlap.

AR NSO has been involved with COVID-19 contact-tracing technology and you discovered that there had been a data breach with the health data of Israelis being made public. Do you think the pandemic has offered a cover for greater surveillance?

EW I think we are less conspiratorial than that. But I think the pandemic creates a condition of vulnerability that could be occupied, and could be claimed in different ways. The project that we’ve done on NSO actually looked at its use of the pandemic to roll out the worst, the most egregious violation of Israeli citizens’ privacy. These tools were developed first, obviously, on Palestinians. I think that we need to be vigilant and, without compromising public health, insist on issues of privacy, because it’s going to be very, very difficult to unroll something that has been rolled out. We’ve seen it before. People made a bargain during the so-called War on Terror, accepting to trade some privacy for more security, and that trade-off was abused.

AR Forensic Architecture also utilises the digital footprints we all leave in its investigations, though. For example, you mention in the book that the running app Strava allowed secret US military bases to be identified, because military personnel were jogging the perimeter fences, leaving a GPS trail.

EW Nothing is predetermined. I think that every territory, whether it’s digital or physical, becomes a site of struggle. We need to struggle with and for technology. We need to struggle for accountability inside the algorithm of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Sometimes we need to use machine learning for human rights. I think that a background in critical theory allows one to do these two things simultaneously; to understand, for example, that Facebook is the site of the biggest surveillance operation in the history of mankind, but it’s also a place where you can find secret information.