On the makeshift dressing table Evelyn has slung her handbag; hairspray and cigarettes lie beside the cheap costume-jewellery that will complete her outfit. It is Santiago, Chile, 1987. Evelyn stretches her arms back behind her neck to fix a choker. Her lipstick already applied, she’s topless, a light brush of hair under her arms and around her nipples. There is a humour to Paz Errázuriz’s black-and-white photograph: a wryness that arises from the juxtaposition of this dowdy room and the plastic glamour of Evelyn, who herself seems to smirk, perhaps glancing to someone out of shot slightly to her left. The dark comedy of Evelyn III, Santiago is absent from another work in the series La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple, 1982–7). In Evelyn II, Santiago we see the subject as a man. He’s handsome: thick dark hair, high cheekbones. He looks a bit sad. Checked shirt, top button undone, sleeves rolled up, belt and jeans.

Magnolia is holding a mirror to the side of her face. She wears a long, flowery summer dress and pearls around her neck. This image, by Graciela Iturbide, seems more staged. While Magnolia is holding a mirror, it’s not seemingly for her own benefit – she’s not looking into it directly. Perhaps it’s more for ours – so we can see the profile that would otherwise be hidden. Her toes, thick with men’s hair, peek out from the rather ordinary sandals she wears. Magnolia was photographed in 1986 against a grimy concrete wall in Juchitán, a town in the southeast of the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

Two years earlier, in a wasteland outside Lima, two figures stand on the balcony of a ruined house: stockings and high heels, makeup and wigs, among the grub and rubble. Their exact gender would be unclear, however, were it not for the fact that one, crouching, mouth open, seems at the point of giving the other a blowjob, the lucky receiver’s skirt neatly hitched up over erect cock. This is one part of a diptych, Ambulantes (the other part captures the same moment, but before the hitching-up), from Sergio Zevallos’s black-and-white photography series Suburbios (1983). The series title has a double reference: to the outskirts of a city (populated by derelict buildings), and to the fact that the transgressive queerness of the act depicted puts the subject – one of the figures is the artist himself, it is unclear which – in a liminal zone in terms of social acceptability.

These artists had greater social and political aims than merely documenting the photographic subjects

All three photographs are more than just portraits of individuals (or self-portraits, in the case of Zevallos). Though fascinating personalities undoubtedly emerge from these pictures, in their photographic work – which in the case of Errázuriz and Iturbide is documentary, while Zevallos’s work is staged – these artists had greater social and political aims than merely documenting the photographic subjects. All three were working in culturally conservative and deeply Catholic Latin American countries during times of political authoritarianism and turmoil. While civil resistance was growing in Chile against the authoritarian regime of Augusto Pinochet, the general’s dictatorial power would only weaken following a 1988 plebiscite. Similarly, though cracks in the one-party rule of Mexico’s socialist Institutional Revolutionary Party were beginning to emerge during the mid-1980s, it remained in power right up to 2000. Zevallos’s work was made under a newly democratic regime in Peru, but with chronic inflation and the constant threat of violent insurrection from the Maoist guerrilla group the Shining Path, life for ordinary citizens was precarious. Seventy thousand Peruvians died in terrorist attacks between 1980 and 2000. For Latin America in general, this was a moment of rule by military force and male-dominated politics, where leaders dealt in signifiers of virility and paternalism. The subjects of the images described above were seen as aberrations from social norms of patriarchal autocracy and male-dominated state and rebel violence. Not that such imagery would have been accepted anywhere in the ‘free’ world at this time either; yet in Latin America, belief in marianismo, the cult of woman as mother and virgin in the figure of Mary, and machismo, the cult of extreme maleness, dominated. Moreover, it was played on by the politicians of the time, leaving cross-dressers and queer figures beyond the political and social pale.

This supposition is supported when the wider work of Errázuriz, Iturbide and Zevallos is taken into account. The latter was part of the Grupo Chaclacayo, which was active between 1983 and 1994, and consisted of Zevallos and Raúl Avellaneda, also Peruvian, alongside Helmut Psotta, a German national and their onetime visiting professor at the art school of the Pontifical Catholic University in Lima. Together and individually they delighted in deeply transgressive, deliberately blasphemous actions and artworks, designed (in modern parlance) to troll the powers-that-be and undermine sociopolitical norms in Peru and on the South American continent. An early performance by Zevallos involved the public parading – in a gross inversion of the Catholic procession – of an altar made of household rubbish to which, among other things, a portrait of Pinochet was attached (La Procesión, 1982). (Curator and writer Miguel A. López, in his 2013 feature on the group, notes that the work can also be seen as a reference to the Mexican feminist Mónica Mayer’s ‘phallus-altar’ sculptures of the late 1970s.) Due to the contentiousness of the work, which ranged from performances staged for the camera to sculptures, drawings and collages (a local critic denounced it as merely ‘paraphernalia of blasphemy’ and ‘vivisection of degeneration’), the collective only managed to stage a single exhibition in Peru, in November 1984. The actions were made in public or semipublic places and played with transvestism, gender fluidity, sex, religious and political symbolism, the display of bodily fluids and the imagery of death. La agonía de un mito maligno (The agony of an evil myth, 1984), for instance, staged on a beach, involved fake funeral rites, the cameo of transvestite Saint Rose of Lima (the beatified Spanish colonist is a recurring figure in the group’s output: she also crops up in a body of work in which prayer cards are lewdly overpainted) and the performance of the Virgin Mother and child in which the relationship has become sexualised. In that identity politics was very much wrapped up in the politics of (postcolonial) nationhood, by way of religion and belief in the family, here the group were treading, with great theatricality, on dangerous ground.

Errázuriz’s aim, however, was not so much to normalise the subjects but to offer them as a counter to the patriarchal image that the Pinochet regime wanted to project

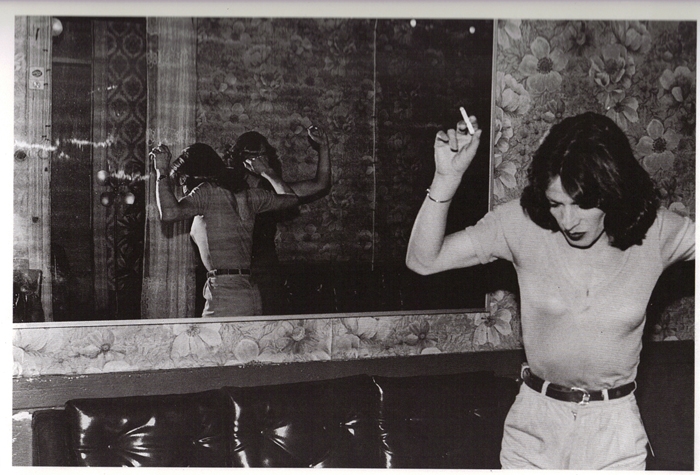

Errázuriz embedded herself with a group of transvestite prostitutes, profiling their lives in both their male and female personas as they went about their day-to-day business. In Coral I–III, La Carlina, Santiago (1987), a series of three images, we see Coral first topless in suspenders, and then in the process of picking up and pulling on a white summer dress. One image from a group of colour photographs titled Talca (1984) shows two of the transvestites entertaining a group of men in a dingy-looking bar. Another image from the same work shows some sort of beauty contest being staged: the broad shoulders of ‘Miss Jaula ’84’ bear a sash. Errázuriz’s aim, however, was not so much to normalise the subjects but to offer them as a counter to the patriarchal image that the Pinochet regime wanted to project. ‘The military and Pinochet drew on [the idea of] the Familial State to legitimize the decision to take and to keep political power,’ the American academic Gwynn Thomas notes in her study Contesting Legitimacy in Chile (2012). ‘Familial welfare (defined most often as protection) was… one that justified the establishment of their authoritarian regime.’ To bear witness and profile those who do not fit this model – as transvestite men traditionally do not – can be interpreted therefore as a political act. If La Manzana de Adán is the most obvious example of Errázuriz’s contesting of political machismo, then it’s not the only one. Indeed, the artist did not just deal in queer imagery. Subtler perhaps is the series Tango (De a dos) (1988), in which she photographed couples dancing in Santiago clubs. Errázuriz’s choice of which dancers she portrayed is telling, though: in almost all the photographs the women are taller and look stronger. The men invariably appear fragile. In one of the several photographs titled Club Aníbal Troilo, Santiago, for example, a middle-aged woman dominates the frame, her perfectly curled hair towering a good half-foot over her partner. He wears something of a scared facial expression. There is a substantial height difference in a second image taken at the same club. Mid-tango, the man looks frail, the woman powerful. A feminist reading can also be found in Iturbide’s work, specifically one that deals in analogy to attack a strongly autocratic paternalistic government. The photograph of Magnolia comes from Juchitán de Las Mujeres (1989), a photography book stemming from the artist’s decade of travels through the narrow stretch of land between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Women emerge as the heroes of this work; indeed Magnolia is one of only a few men present within the book’s pages. The women are invariably big in build and strong in demeanour. Juchiteca con cerveza (1984) shows a woman dominating the image and landscape behind her as if she is larger than it all. She’s laughing as she holds her beer between two fingers and thumb in front of her face: almost, even, as if she’s laughing at the phallic bottle itself. Likewise, reptiles (which Freud argued were symbolic of the male genitalia) frequently recur in Iturbide’s photography, controlled or subservient to women. Shot from below, the woman in Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas (1979) is shown wearing a halo of iguanas (seemingly still alive) on her head. In Lagarto (1986) two women hold a carved wood alligator, and in Padrinos del lagarto (1984) a woman sits with a live baby alligator on her lap.

It would be hard to argue that any of this effected much change in the artists’ respective countries at the time. In 1989, as the violence in Peru grew worse, Zevallos and the other members of Grupo Chaclacayo fled to Germany. Errázuriz and Iturbide stayed put, layering their imagery in coded symbolism. Yet arguably dissent against authoritarianism, even if it fails to achieve its aims, is something to be admired. More recently, however, as most of Latin America has settled into the stability of democracy and, for better or worse, neoliberalism, these artists are gaining recognition for the small acts of subversion inherent in their work. Iturbide is recognised as one of Mexico’s most important photographers (having received the Hasselblad Award in 2008), Zevallos’s work was included en masse at the 2014 São Paulo Bienal and Errázuriz was the subject of an extensive solo retrospective at Madrid’s Fundación Mapfre that closed earlier this year, and in 2015 was one of two artists sharing the Chilean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Yet for all this institutional acceptance, the work still has a power to shock. There is a grimness, a sense of sexual-political anarchy to much of these artists’ work: its subjects display an insurrectionary otherness, one that sits uncomfortably in our sanitised modern age.

This article was originally published in the May 2016 issue of ArtReview