The first contemporary artist to curate a major exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, Tan takes a loosely psychiatric approach to the museum’s collection and archive

Fiona Tan is the first contemporary artist to curate a major exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, drawing on its resources to reflect on the institution’s dual status as an art museum and a repository for Dutch cultural artefacts. Monomania’s ostensible subject is nineteenth-century psychiatry; the titular term has long since slipped into demotic language, but for nearly a half-century it denoted an obsessive tendency afflicting an otherwise sound mind. (Erotomania, narcissism and pyromania were among the subcategories identified by psychiatrist Jean-Etienne Esquirol.) Spread across 11 loosely thematic galleries containing artworks, archive materials and objects disinterred from storage – from Javanese masks to tea cosies – it’s a compelling, if flawed endeavour. The psychiatric angle, however, might well be a red herring. The Indonesian-Australian Tan, one senses, is keener to stress the fallibility of categorisation itself, whether in relation to medical science or, indeed, to museum curating.

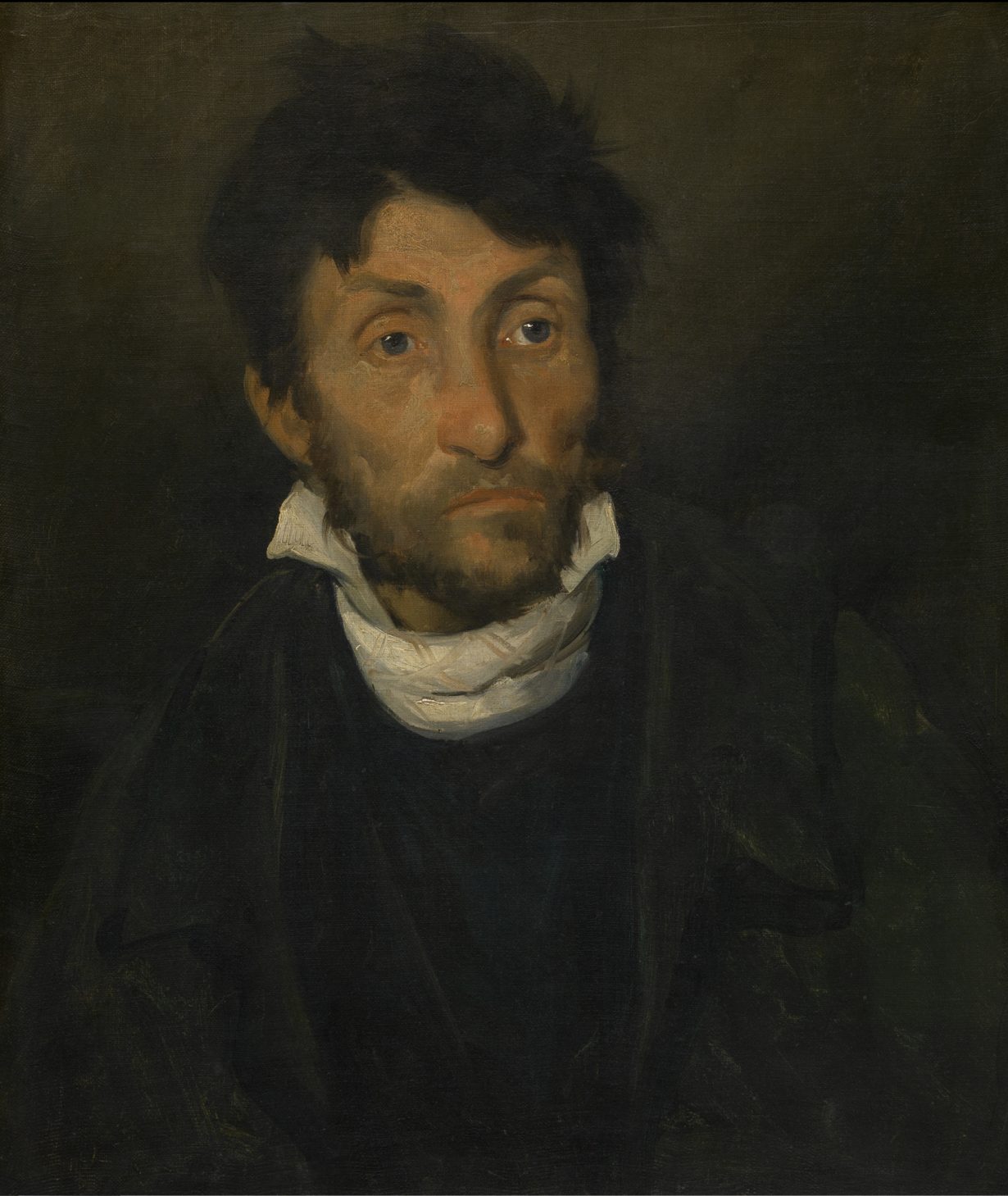

We’re alerted to this from the first exhibit, a portrait by Théodore Géricault, the so-called Portrait of a Kleptomaniac (c. 1820–24). Quickfire brushstrokes cohere into a likeness of a tousle-haired, hollow-cheeked man whose thousand-yard stare refuses to meet our gaze. It’s an extraordinarily empathetic painting, but its specificity is murky. The work is one of ten portraits of insane-asylum patients that Géricault painted towards the end of his life. Beyond this, little is certain: its title was applied nearly 40 years after the artist’s death by a retired doctor attempting to sell several of the portraits. The attribution of specific characteristics to the sitters was probably fanciful – as Tan puts it, ‘a sales pitch’. What in this man’s gauntly handsome features marked him as a pathological thief?

The question leads us into the realm of discredited pseudoscience, and the widespread nineteenth-century belief that character traits were readable in physical attributes. Tan devotes an entire gallery to the subject, fielding an 1840s phrenological chart, a copy of Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) and a row of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s delirious eighteenth-century sculptural character heads. It’s fascinating, an exemplary instance of serious research-based exhibition-making. Yet the display also unsettlingly suggests something like an intellectually acceptable freakshow. The feeling is reinforced by a room containing illustrated, mostly annotated case studies of supposed monomaniacs. It’s horrifyingly clinical: one ‘before and after’ shot from Auguste Voisin’s Leçons cliniques sur les maladies mentales (1876) gives us an albumen print of a young woman suffering from ‘lypemaniacal madness’; in a second image she’s radiant, apparently cured via a three-month treatment involving ‘morphine hydrochloride’. It’s hard not to feel you’re rubbernecking on the cruel stupidity of the past.

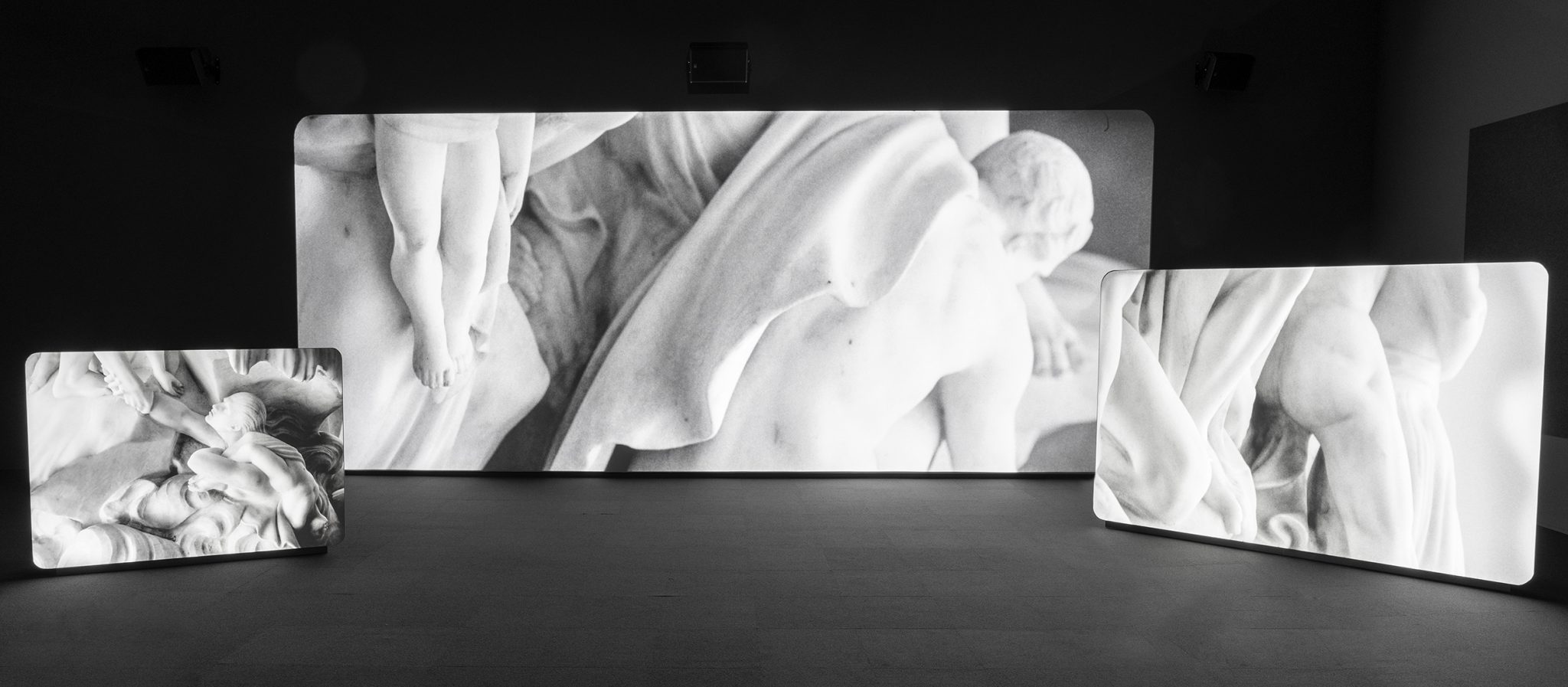

A concern of a different sort rears its head in the show’s second half, when the display – having so far taken the dry, vitrine-dependent character of a pedagogical exhibition – begins to echo installation art. One gallery contains a knee-level mirrored platform, onto which are placed several dozen knitted swatches as lace christening gowns dangle from the ceiling. It’s Louise Bourgeois-esque, or like a supernatural shot from a 1970s horror movie, and this sudden pivot to uncanny theatricality is awkward to say the least. If it scans as camp, that surely wasn’t the intention.

Tan’s own contribution is Janine’s Room (2025), a three-channel video in which a woman, surrounded by a labyrinth of books and papers, writes and reads obsessively as the camera pulls closeups on her lace curtains and a localised sandstorm gradually buries her typewriter. It’s another jarring, out-of-place tonal shift. Yet these criticisms are praising with faint damnation: not many museum exhibitions have engaged me like this one, and I suspect the fluidity of mood and form comes back to Tan’s stated distrust of immutable taxonomies. We’re reminded that although Esquirol’s formulation is now seen as primitive in psychiatric circles, it was an enlightened school of thought in its time: while previously you were either sane or irredeemably mad, ‘monomaniacs’ were deemed curable. By extension, Tan argues in the catalogue, modern thinking around mental health may soon be seen as equally backward, and even what we imagine to be objective may soon be disproved and supplanted.

Monomania at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 4 July – 14 September

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next: Gala Porras-Kim’s work asks, are museums for the dead or the living?