Flanagan’s Wake at Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles unfolds a lyrical, sentimental – and NSFW – tribute to the performance artist Bob Flanagan

‘Flanagan’s Wake’ was the title of a 1996 eulogy in Artforum by Dennis Cooper to his friend the poet and performance artist Bob Flanagan, who had just died of cystic fibrosis. Cooper tells how they met during the late 1970s at Los Angeles’s Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center; early on, Flanagan stuck to ‘gentle, Charles Bukowski–influenced poetry’, wrote Cooper, but his predilection for sadomasochistic kink soon infiltrated his work. After he fell in love with Sheree Rose, a photographer, performance artist and dominatrix, he became notorious for his provocative performances, usually in collaboration with Rose. For their collaboration Nailed (1989), Flanagan nailed his penis and scrotum to a board while singing If I Had a Hammer.

Sabrina Tarasoff, the writer and critic who curated the exhibition Flanagan’s Wake, has nailed her own colours to the mast of Beyond Baroque’s history. (The institution still operates, though without the same cachet that it cultivated during the 1970s and 80s.) For Made in LA 2020 (2021), Tarasoff built a hair-raising haunted-house installation filled with material related to Beyond Baroque, including an NSFW section on Flanagan and Rose.

At Kristina Kite, a more lyrical and sentimental tribute to Flanagan’s legacy unfolds, including only one artwork attributed to him – a collaboration with Rose and his friend Mike Kelley – appropriately sequestered in the back room. (That video, 100 Reasons, 1991, documents Flanagan’s bare arse turning incrementally redder as it is spanked by Rose, while Kelley reads out a hundred suggested names for a paddle.)

The primary conceit of the exhibition is that we are encountering the aftermath of a party: at once a post-funeral wake, a BDSM orgy and a metaphor for a wildly generative and uninhibited life now extinguished. The gallery (once a bank), with its chequered black and white floor, sometimes feels less like an art space than a vacant venue, opportunistically squatted. Everywhere loll the cast resin and latex balloons of Michael Queenland’s Black Balloon Group (2018), mordantly floor-bound. Amy O’Neill’s Post Prom Dance Floor Version Two (1999/2022) takes centre stage, both figuratively and actually: a low square podium is flanked by coloured stage lights and strewn with streamers, a balloon and confetti, irregularly hand-shredded so that it appears as the debris of some terrible explosion. Her work overlaps, almost uncomfortably, with George Stoll’s sculptures, which are indistinguishable from desultory scraps of tinsel taped to the wall or hanging streamers turning in the breeze. So self-effacing they almost disappear, Stoll’s interventions are in fact lovingly handcrafted from Mylar, aluminium foil and painted brass.

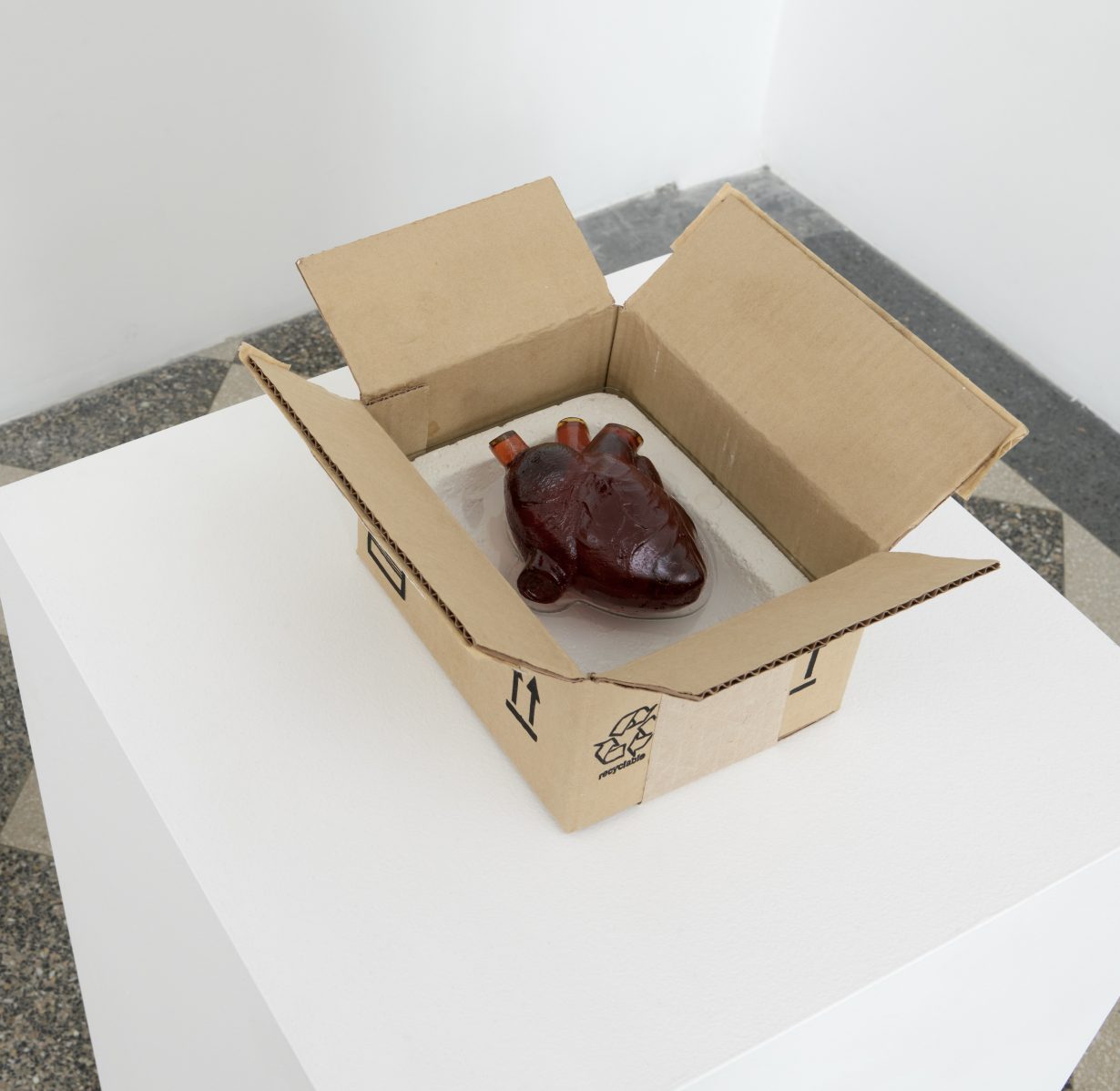

Hyperrealistic mimetic handicraft continues with Robert Gober’s Heart in a Box (2014–15), a cast glass heart packaged in an astonishing simulacrum of an Amazon box made from painted aluminium, and Julie Becker’s photographs of the corners of tawdry interiors that may or may not be studio reconstructions. But where these works collectively take flight is in their conversation with Nayland Blake’s bondage restraints, which literalise structural codes (social, aesthetic, art-historical) through artworks that are, as with these other pieces, nontraditional craft objects. Pink Posture (2019) is a steel ‘spreader bar’ with pink leather cuffs at each end; Single Restraint (1990) is a wall-mounted triangle of canvas with buckles that turn it into a kind of straitjacket. Of all the artists in the show, Blake gets closest to the ethic of self-control and restraint (not constraint, the word I at first reached for) in Flanagan’s work, touching also on the ecstatic freedoms it could unleash. Kelley, incarnated here as a kind of patron saint of the scene – his series of printed banners Pansy Metal/Clovered Hoof (1989/2022) hanging high over the room – understood this duality too.

It took me a while to come around to the inclusion here of Becker’s video installation Suburban Legend (1999), in which she projects The Wizard of Oz (1939) overdubbed (intrusively) by Pink Floyd’s album The Dark Side of the Moon (1973). In a photocopied handout, Becker recounts the longstanding rumour that the psych-rock concept album functions as an alternative soundtrack to the movie, replete with uncanny coincidence. She admits to getting bored after the first hour, but highlights some good bits anyway. Suburban Legend, like Blake’s restraints, like this exhibition, involves two (or more) things shackled together. I’m not sure if Flanagan’s Wake led me to deeper insights into Flanagan’s work, but it certainly added to my understanding of work by another diverse group of artists. Which is quite a legacy.

Flanagan’s Wake at Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles, through 5 November