From Europe’s bloodlands to the rainforests of Brazil, the late artist witnessed destruction on industrial scales and turned it into eloquent sculpture. In January the violence came for his own work

‘Structure broken at four points, one element completely separated from support.’ This is the clinical assessment of a wood sculpture by Frans Krajcberg by the conservators convened by the new Brazilian administration. The work was one of many in the public collection damaged by fanatical supporters of former president Jair Bolsonaro as they rampaged through the Planalto, Brazil’s seat of government in Brasília, while attempting to force through a coup in January. Galhose Sombras (Branches and Shadows) is typical of Krajcberg’s use of found wood; here the debris from a tree burned by loggers has been painted white and emerges from a similarly hued wall-hung plaque. The sculpture, when intact, had a ghostly and melancholic form. Which was apt given that the artist spent a lifetime using his art in the service of ecology and to decry the destruction of the Amazon and Atlantic rainforests. That the work was so badly damaged by supporters of the far-right Bolsonaro – during whose final month as president, December 2022, deforestation was 150 percent greater than in the previous December – has inspired a new appreciation of the artist’s political impetus.

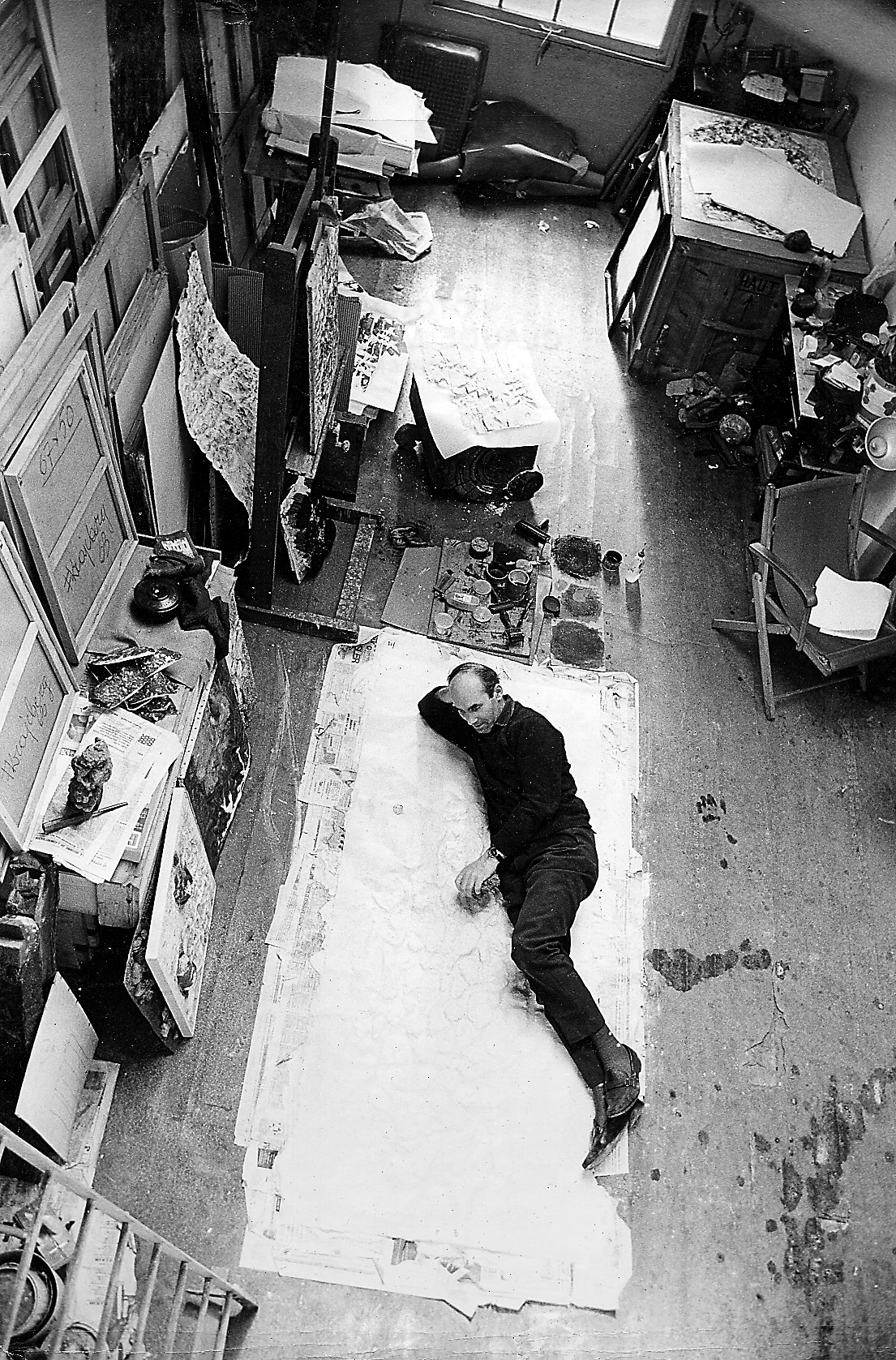

Krajcberg, who died in 2017, described himself as an angry man. His art, though beautiful in form and poetic in imagery, was a manifestation of that fury. He was born in Poland in 1921 to a Jewish family, his mother a communist activist, and saw the majority of his relatives exterminated in Nazi concentration camps. He himself escaped east, and took a degree at Leningrad State University that combined art and engineering, a pairing that would come in handy when his later organic sculptures increased in scale and became architectural in ambition. During the 28-month Siege of Leningrad, he managed to slip out of the city with his girlfriend, a first love who, as they weaved between enemy lines, was killed in the forests beyond Minsk. Disguising his surname and continuing alone, he joined the Polish First Army and was posted to Uzbekistan, eventually participating in the liberation of Warsaw, a position that forced him to bear witness to the aftermath of the Nazi atrocities. He would later describe desperately searching the Polish capital for his family, but finding no trace.

Dislocated, with no sense of home, he moved itinerantly across the continent, spending months in Stuttgart with members of the former Bauhaus school, before landing in Paris, where he met Fernand Léger and Marc Chagall. The horrors of war had left him traumatised, and a chance to travel to Brazil as a refugee offered a tantalising new start. He landed first in Rio de Janeiro, homeless and sleeping on Botafogo Beach, and then went to São Paulo, a city he hated. Lasar Segall, a fellow East European émigré who had arrived in the country decades prior, suggested he take himself to the countryside in the neighbouring state of Paraná: it was only then Krajcberg found something approaching peace.

The artist’s first nature works were simple still lifes of Brazilian flora, but by the end of the 1950s these had morphed into the darker, more formally complex Samambaia (Fern, 1956-58) series, the leaves rendered in dark brooding oil paint on canvas, heavy with shadow and often set against a background of scratchy, messy brushstrokes. These won him plaudits and a growing fame, cemented by winning the prize for best Brazilian painter at the Bienal de São Paulo in 1951 (Andy Warhol beat him to the grand prize; Krajcberg also won a prize at the Venice Biennale, in 1964), which, in turn, gave him some security. He started to grow disenchanted with the idea of representation, however, at which point the seeds of Krajcberg’s almost animist approach to artmaking flourished. The idea of painting nature affirms an anthropocentric separation from it. The artist began to see himself as a co-creator with the natural world; during the 1960s he produced his ‘Reliefs’, oil works that trace the surface of a tree trunk, for example, or stony ground. Abandoning paint altogether he began work on a body of assemblages, gathering together dried vines, stones or logs into a frame. Red composition (1965) is made up of preserved plants painted with deathly red natural pigments on a wood pane. Although these assemblages have a certain gothic edge, this work was essentially celebratory.

His relationship with nature was to become far more political however with the construction of Brasília, which is ironic given recent events. After the Oscar Niemeyer-designed new capital had been inaugurated, in 1960, the 2,070km Belém–Brasília Highway was constructed, cutting through huge swathes of previously wild or sparsely inhabited terrain. Krajcberg took the destruction personally, the insult reiterated after he moved to the northeastern state of Bahia during the 1970s, building a treehouse ten metres up in the branches near the town of Nova Viçosa. Here he lived, worked and witnessed the slow clearing and burning of the rainforest by loggers, cattle farmers and gold miners, some operating legally, many not. From then on, he said, he worked ‘not only with the beauty of nature’s forms, but also with nature that is being destroyed. My sculptures are like the memorial of the disaster I see, in the middle of which I live.’ He built assemblages from burned timber, which grew in size and ambition as the situation got worse and illegal logging and mining increased. At a posthumous survey of the artist last year at São Paulo’s Museu Brasileiro da Escultura e Ecologia, the main gallery of the institution was filled with a forest of these works: hollowed-out roots that climbed spiderlike across the concrete floor; trunks, some painted with natural pigments, polished or carved, others left natural and either half decomposed or fire charred, that reached totemically to the gallery ceiling. Each had their own personality, like ghosts haunting the space.

The ‘Revolts’ – the term he used for the works made of salvaged, burned forest wood – are the most poignant. Their emotional resonance comes across not just as symbols of environmental destruction (the most common reading of the work), but because they are inextricably linked to the artist’s family history. Claudia Andujar is another Brazilian Jewish artist whose family perished in the Holocaust, and she has spoken that her years-long fight for the Yanomami indigenous people was driven by that memory. For Krajcberg, too, the Revolts seem a revolt against and a revulsion for the violence of humanity. ‘I show the unnatural violence done to life,’ the artist said. ‘I express the revolted planetary consciousness. Destruction has forms, although it speaks of the non-existent. I’m not trying to sculpt. I am looking for forms for my cry. This burnt bark is me. I feel myself in the woods and the stones.’ Seeing billows of smoke choking the sky over the forest was, for the artist, to witness fascist destruction all over again. For good measure, he described himself as a ‘burnt man’.

The vandalisation of Galhos e Sombras in January was not captured on film, but plenty of other CCTV and camera-phone footage documents the ripping of paintings, the smashing of antiques and the destruction of furniture as more than a thousand people rampaged through Brazil’s Congress and presidential palace. It would be easy to assume a mob mentality, to dismiss the far-right supporters as high on fake news and endorphins, but that might excuse what seems a calculated and systematic attack. Like a forest being cleared for agriculture or mining, hardly a square metre of the complex was left unscathed. The Bahian government, which handles Krajcberg’s legacy, has said that the artist would not want the work repaired and would have demanded that the sculpture be left broken; like all his work, a testament to the violence of man.