Two new books on the life of political philosopher Frantz Fanon examine ideas of embodied trauma

Martinican psychiatrist and race theorist Frantz Fanon died in 1961 at thirty-six in Bethesda, Maryland in the final stages of leukaemia. Having devoted his short life to denouncing the complex psychological systems devised by colonial regimes to dehumanise people of colour, Fanon had – in retrospect somewhat ironically – been flown to the US National Health Institute by the CIA at the request of the Algerian provisional government.

Fanon enlisted with the French Army as a young man during the Second World War, came home to the Caribbean disillusioned by what he had witnessed of French ‘universalism’, then returned to France to study psychiatry on a veteran’s pension before moving to Algeria in 1953 to direct a psychiatric hospital outside of Algiers. Within a year of his arrival, Fanon had fully committed to his adoptive country’s struggle for liberation. By 1957, he was deported by the French for his connection to key leaders in the National Liberation Front (FLN) and went into exile in Tunisia with his new allies. He remained dedicated to post-colonial emancipation in a number of roles: as a clinician in a psychiatric hospital in Tunis, the FLN Ambassador to Ghana, participant at conferences across Africa and author of the series of articles what would become his most well-known work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961).

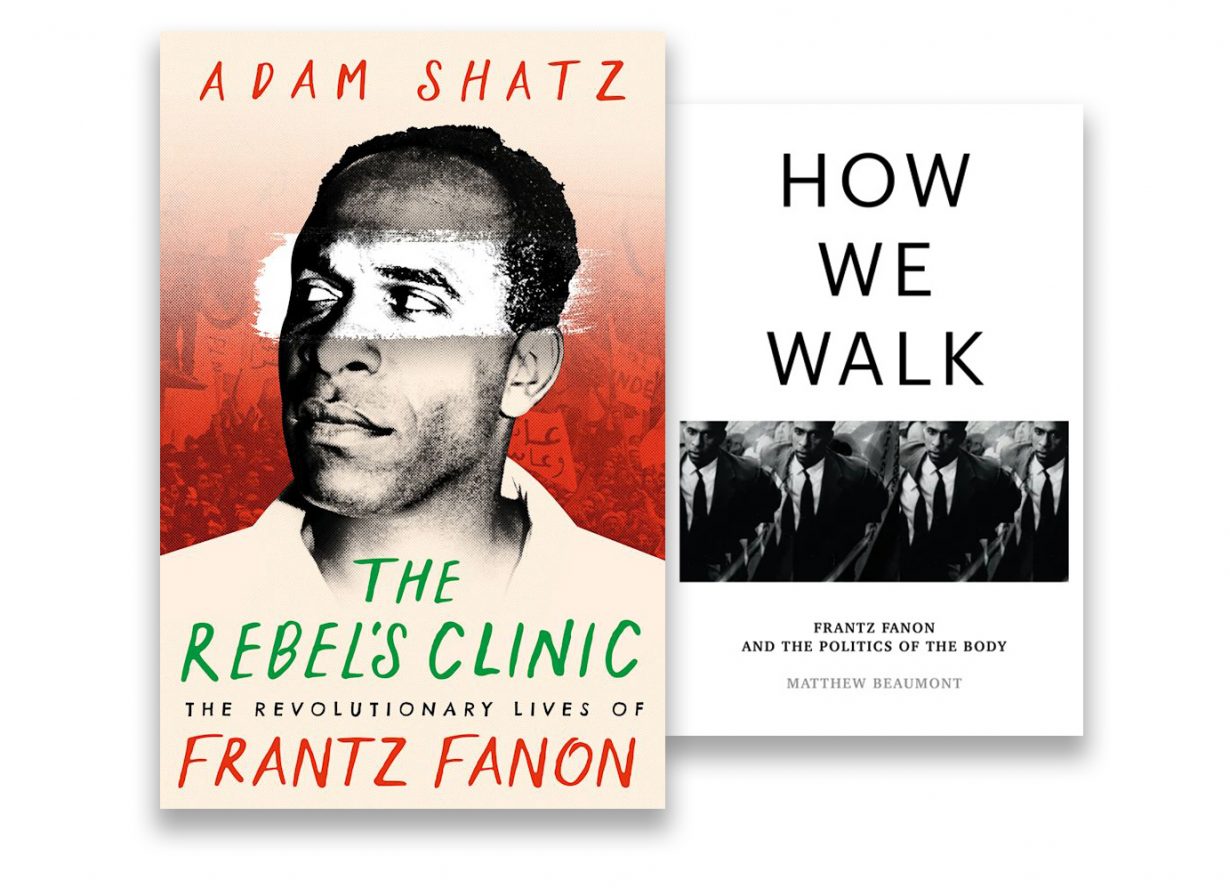

Now, two new books focus on embodiment in Fanon’s legacy, both in clinical work such as his medical thesis on a neurological disorder known as Friedreich’s ataxia, which affects the way people walk or their gait, and his broader analysis of the ways racism affects the nervous system and socio-somatic mobility. Matthew Beaumont’s How We Walk: Frantz Fanon and the Politics of the Body is a case study in what can go wrong with an attempt to anchor a notion of political embodiment too firmly in Fanon’s subsequent mythologisation as heroic male firebrand theorist. Adam Shatz’s biography, The Rebel’s Clinic, is a more careful portrait of the anti-racist project that was Fanon’s life, both as a psychiatrist and as a person.

Both writers grapple with what Shatz calls Fanon’s belief in ‘the regenerative potential of violence’, or the idea that violence and/or shock could function as ‘a kind of medicine, rekindling a sense of power and self-mastery’. However, where Beaumont’s book neglects to examine some key gendered and able-bodied assumptions that underpin Fanon’s theories about the body’s capacity to fight, Shatz positions such exclusions as part of Fanon’s reckoning with the contradictions of his own status within the Black middle class in Martinique and his conflicted identification with French society.

In the first chapter of How We Walk, Beaumont sets a kind of primal scene, where Fanon paces about his office expressing himself on subjective emancipation with such complete mastery that his words will require no revision. Ideas pass from his body onto the page, retaining the syncopation of his physical movement. The anecdote is presented as evidence for the author’s thesis that Fanon considered an ambulatory body as the necessary ground for liberation. But the way Fanon composed his missives strike me as an awkward example of how man’s liberation is bound up with physical movement. To walk in circles while a presumably seated and relatively immobile woman writes down every word introduces the problem of (gendered) interdependence; Fanon’s expression depends utterly on the reciprocal presence of his wife Josie, as well as her undivided attention, intellectual devotion, and skill at transcription.

Beaumont points out – an argument which, it must be said, Alice Cherki, Diana Fuss and others have made before him – that social alienation can and does manifest as a physical disability, and that Fanon’s work was key to understanding how racism and islamophobia are vectors for such social alienation. But his conclusion, that ‘[f]or Fanon, the fluid, self-emancipating gait opened up by female Algerian militants in the late 1950s outlines the utopian possibilities of a properly post-colonial future’, calls for mere rejection of structural forces, or, to just stand up and walk unafraid. Beaumont’s conclusion ignores the fact that the women who participated in the struggle for liberation in Algeria by walking the city were largely upper-class women or university students – and so had sanctioned infrastructure for their perambulations. They walked within a supportive context, in other words. That Beaumont champions walking as the medicine for political debilitation without acknowledging that context is to miss the point that embodiment entails relational awareness rather than autonomy.

On the surface, Shatz’s biography of Fanon reaches a strikingly similar conclusion: ‘if there was one thing [Fanon] admired, it was active, bodily resistance to oppression’. Shatz arrives at this by centring Fanon’s body, carefully retracing the analytical conclusions Fanon drew from his lived experience both in public space and in the various psychiatric clinics in which he worked. Shatz describes continuity between Fanon’s experience of subtle internalised racism in the Black middle-class society of his childhood in Martinique, and the adult’s analysis of analogous racist structures in mid-twentieth-century French intellectual life. By positing embodied knowledge as the ground for Fanon’s thought, Shatz fully incorporates the gendered, class-based and institutional support structures that defined Fanon.

For example, in chapters ‘Wartime Lies’ and ‘Black Man, White City’, Shatz offers a thorough exploration of Fanon’s personal disillusionment with French universalism during his military service in the Second World War and his medical training in Lyon. These stories contextualise his clinical practice in Algeria and then Tunisia, specifically his commitment to shock therapies. ‘To shield patients from the world, Fanon felt, was to encourage a “thingification” of their condition… and therefore of the patient’, writes Shatz. Fanon sought visceral confrontation with what he called the ‘toxicity of reality’ throughout his life and advocated for the same in his experimental treatment plans.

Do shock and exposure repair the damage done to the body and mind of those who live in the wake of colonisation and enslavement? Shatz does not pass judgement on this point, closing instead with a catalogue of the many ways Fanon’s legacy has been embraced or contested by a broad range of posthumous interlocutors, from left-wing Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia to the fictional disgruntled superrich on HBO’s The White Lotus (2021–). But the link Schatz makes between Fanon’s embodied experience and his understanding of violence nevertheless evokes a range of critically relevant historical questions. Such as: What forms of embodiment did Zohra Drif employ when she walked in the Milk Bar in the center of Algiers’ European quarter in September 1956 dressed in impeccable Parisian fashion, ordered, put a bomb under the counter, finished her ice cream and then walked out before it exploded, killing three and injuring dozens? Were she and the dozens of other Algerians arrested and tortured in retribution cleansed of their psychosomatic abjection under colonial regimes through acts of emancipatory violence? Further, the French military regime’s response during the Battle of Algiers (in which context Drif’s attack took place) contributed to a decisive withdrawal of international support for colonial control over Algeria. Does such a pyric victory confirm Fanon’s understanding of the embodied resistance as ‘medicine’ for the individual, or complicate it?

The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon by Adam Shatz. Bloomsbury, £25 (hardback)

How We Walk: Frantz Fanon and the Politics of the Body by Matthew Beaumont. Verso, £16.99 (hardback)

Natasha Marie Llorens is a curator and writer based in Stockholm, where she is professor of art and theory at the Royal Institute of Art and co-director of the Center for Art and the Political Imaginary.