The Marxist literary theorist revealed how cultural artefacts could illuminate the ideological underpinnings of everyday life

The Westin Bonaventure Hotel opened in Los Angeles in 1977 with a revolving restaurant and bar on its top floor. In a 1984 essay later expanded into the book Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), Fredric Jameson, the Marxist literary theorist who died at the age of 90 last Sunday, describes himself wandering in bewilderment through the ‘hyperspace’ of the hotel, which he treats as characteristic not only of postmodern architecture but of postmodernity more broadly: depthless and disconnected from history. The hotel presents as a world unto itself repelling the city beyond with its ‘reflective glass skin’. Filled with escalators and elevators that do not simply facilitate movement around the building but function as a ‘dialectical intensification’ of movement as such, the hotel confounds perceptions of volume and depth via ‘bewildering immersion’, taking ‘vengeance’ on those who enter it.

By all accounts Jameson, who taught literature as a professor at Duke University since 1985, was a generous and engaging teacher, and in my experience his writing is also generative and rewarding to teach. In the preface to The Political Unconscious (1981), he remarks that ‘texts come before us as the always-already-read; we apprehend them through sedimented layers of previous interpretations’. This is especially true of those that have become as canonical as some of his own but even his more familiar works reward re-reading, throwing up surprises and new questions. I had forgotten, for example, that his analysis of the Bonaventure Hotel is immediately followed by a strangely compressed passage claiming that the hotel environment has an analogue in the war machinery introduced by the US military in Vietnam, making clear that the sensory implications of postmodernity extended far beyond the ‘complacent and entertaining’ realm of leisure and aesthetics.

‘Always historicize!’ – is a famous Jamesonian dictum, and it helps to understand his own decision to pursue the scholarly analysis of literature rather than something more directly political in the context of a historical moment in the USA in which political struggle was in abeyance. Born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1934, Jameson completed a PhD on Jean Paul Sartre at Yale in 1959, and published and taught consistently from the early 1960s until his death. But his work was always diagnostic rather than simply symptomatic of the historical conjunctures in which it was composed. Indeed, the question of how to reignite a sense of revolutionary possibility under late capitalist social conditions that seem inimicable to transformation is explicitly thematised in much of his work, most famously in his account of postmodernism, which precisely theorises a particular mode of ahistoricity or at least a ‘weakening sense of history’ as a historical phenomenon. He eschewed the banal positivism of contextualisation in favour of an attentiveness to form, as he remarked in a 1984 essay: ‘There is of course no reason why specialized and elite phenomena, such as the writing of poetry, cannot reveal historical trends and tendencies as vividly as “real life”’.

Jameson had a gift for the synoptic and even programmatic – such as in his tour-de-force ‘Periodizing the 60s’ or the weird manifesto ‘An American Utopia: Dual Power and the Universal World Army’ – but from the cinema of Edward Yang to the architecture of Rem Koolhaus, the detective fiction of Raymond Chandler to the realist novels of Honoré de Balzac and the science fiction of Philip K. Dick, the specific often provided Jameson’s route to the general; the close analysis of any film, building or novel always related to his analysis of the social totality. For Jameson, following Marx, capitalism is a totality and a concept of totality will be necessary to overthrow capitalism, but how to apprehend, comprehend or represent something that is not only vast and complex but characterised by alienation and reification? ‘No one had ever seen that totality’, he writes in a book on Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, ‘nor is capitalism ever visible as such, but only in its symptoms.’ Allegory is a term whose meaning I always struggled to grasp but Jameson’s analysis of the late Soviet film Days of Eclipse (1988) in The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System (1992) – in whose dusty and decrepit scenes he discerns a ‘convulsive shift of reference’ signalling the shift from state socialism to the market economy – finally enabled me to understand it.

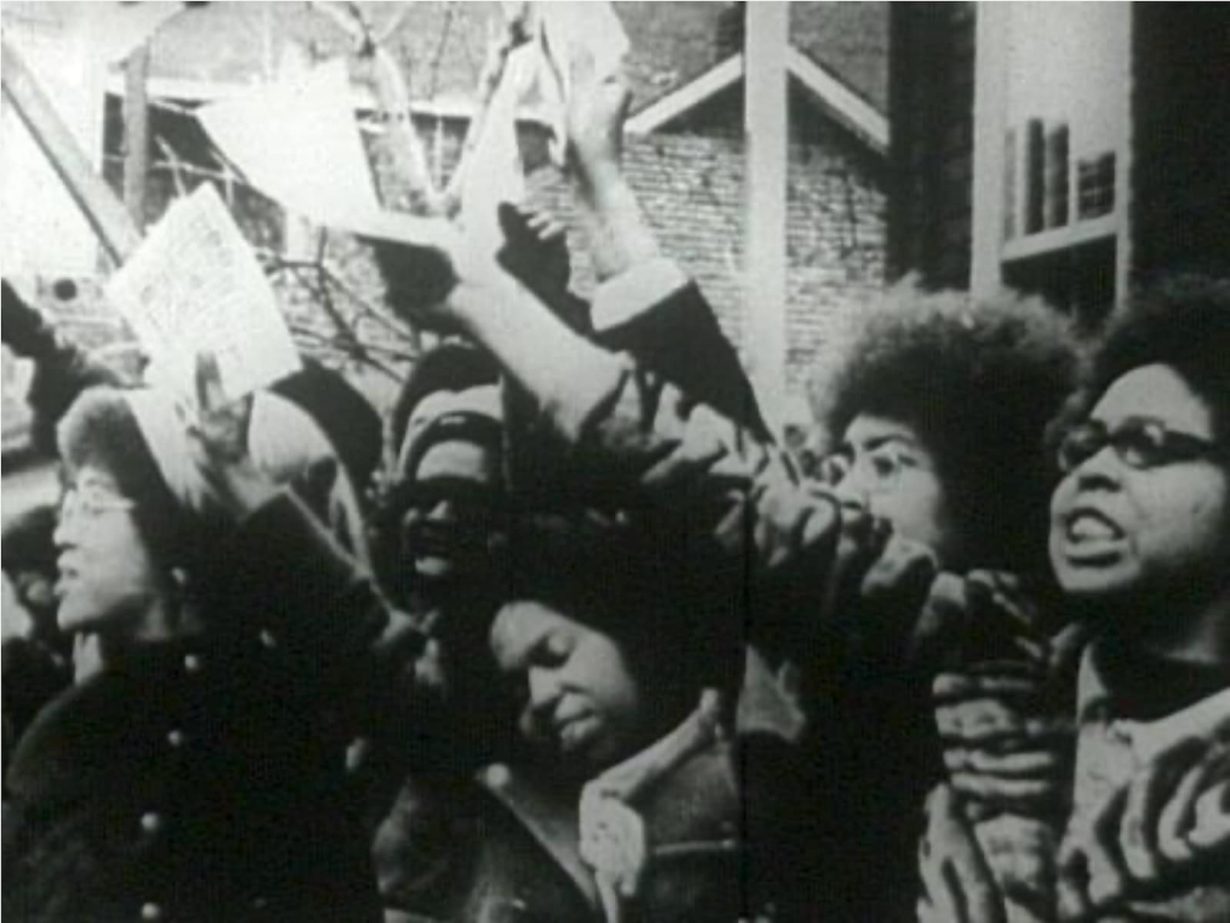

In a 1990 essay introducing the concept of ‘cognitive mapping’, which Alberto Toscano explains in the 2016 Social Text essay ‘The World is Already without Us’ responds to Marx’s observation that the ‘taste of the porridge does not tell us who grew the oats’, Jameson discusses the example of the League of Black Revolutionary Workers in order to probe the relation between the general and the specific. The League, a movement formed around the auto industry in Detroit in the late 1960s, believed that their local movement could be generalisable and began to travel to discuss their work with comrades across the world. They also produced a film – Finally Got the News (1970) – as a means of disseminating their political strategies. Jameson argues that in setting their sights on the global their local struggle unravelled beneath them. Yet in a typically dialectical rhetorical flourish, he claims that this very failure was ironically a form of success, in that a film and book representing this ‘complex spatial dialectic’ survives documenting this contradiction.

Jameson reflected on the limits to the political utility of literary criticism, writing in The Political Unconscious that: ‘It is clear that the work of art cannot itself be asked to change the world or to transform itself into political praxis’. Yet as a committed dialectician more interested in valences and antinomies than in syntheses, he sought to explore how artworks could illuminate the ideological underpinnings of a particular epoch or society in ways that would also gesture towards different possibilities. Jameson’s interest in utopia was continuous with his interest in history and its troubling disappearance in the late twentieth century: utopianism signals a desire for a future that is radically different from the present.

The phrase ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’ is often attributed to Jameson, though he claimed it came from elsewhere. Jameson remained incredibly prolific, publishing multiple books in the last year alone. Discontinuous, splintered, bitter, ravaged, torn – Theodor Adorno argued that Beethoven’s late style, and the late work of significant artists more generally, could be understood as catastrophic. For Jameson, it might make more sense to say that his style was consistently informed by an interest in a lateness that seems permanent and in an end that never arrived, an end he nonetheless remained committed to up to the very end of his life.

Hannah Proctor is the author of Burnout: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat (2024)