Selected by Adeline Chia, reviews editor, ArtReview Asia

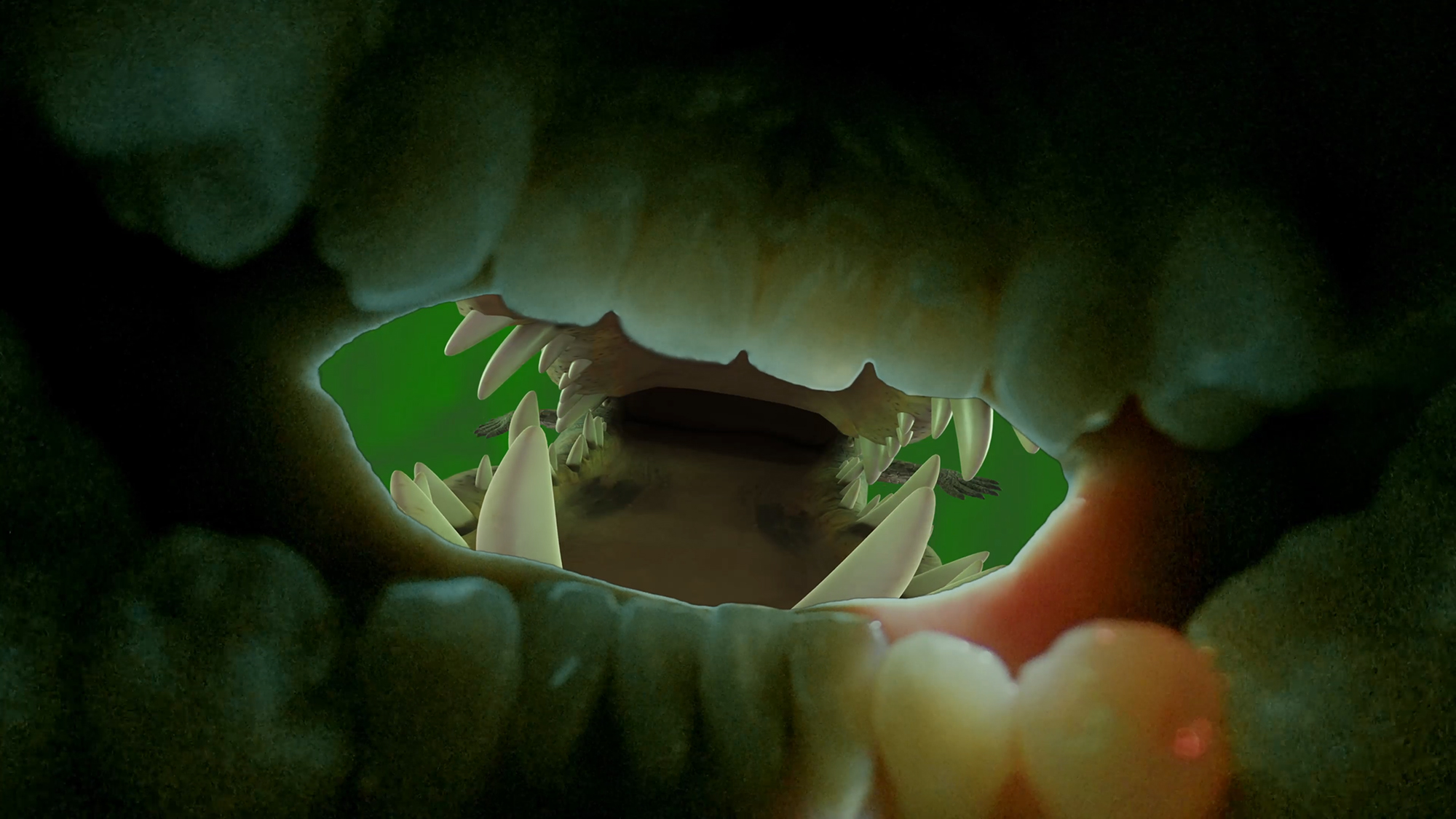

We’ve all heard about putting yourself in someone else’s shoes to understand their point of view, but what about diving into someone else’s mouth? In the video mouthbreather (2023), Tiyan Baker enables just this, placing a tiny 360 camera in her mouth so that we see the world through a narrow opening between her teeth.

Baker’s father is Australian Caucasian; her mother is from the Bidayǔh Indigenous community in Sarawak, in Malaysian Borneo, and one of its native tongues, Bukar, is the subject of the film. The work explores how language can shape our consciousness and worldview, not just rationally but viscerally. As the video explores the hills, streams and forests of Baker’s ancestral lands, we hear Baker speak in garbled Bukar, her words mangled by the camera in her mouth. Later, as we visit a crocodile farm, a voiceover in a deeper register narrates the perspective of the crocodile, a creature that features heavily in traditional Bidayǔh art and legend: “I remember swimming in the swamp with children from the village. Long ago I knew how to be a human,” it says. As Baker treks through the forest, the identity of the speaker shifts again, to an unspecified entity that declares itself the origin of language and knowledge: “I taught you the names of birds… fruit trees… things that live in the jungle. The reason you can see these things is because you can name them.”

This work generates a discomforting experience in which the viewer’s perspective is dominated by Baker’s cavernous pink palate, white teeth and tongue. Like endoscopic images, the view is extraordinarily intimate, poised somewhere between a medical examination and a sexual encounter. Anchored in the corporeality of the mouth, mouthbreather places us in situ, highlighting the fact that we produce language not just through the mind but complex interactions of tongue, lips, jaw and pharynx. Baker’s works often deal with Indigenous culture and heritage, and how these have been eroded, appropriated or transmuted in contemporary society. Here, she highlights the rapidly declining use of her mother tongue due to the competition of Malay and English, and the loss of the knowledge that Bukar contains, which includes an Indigenous cosmology that is connected to the wider nonhuman world of animals and spirits.

Based in Newcastle (or Mulubinba) in Australia, Baker works in installation, photography, video and sculpture. Her works engage in a continuous unfolding dialogue with her ancestral culture and its place in contemporary life. On one level, she celebrates the landscapes and lifestyles embodied in Bukar, indirectly arguing for stronger preservation of Indigenous minority languages, which is an ongoing and uphill effort by minority groups in East Malaysia. nyatu’ maanǔn mungut bigabu (2021) comprises a series of autostereogram photographs, which are 2D images with repeated patterns that hide an underlying 3D image. For example, embedded in a photograph of durian husks is the word nyatu, which means ‘to collect fallen fruit’; in an image of hanging plant-shoots is hidden the word mungut, which means ‘to pick only the young buds’. ‘Bidayǔh language has hundreds of terms for activities that speak to a daily rhythm of moving through the jungle and working intimately with plant life,’ the artist wrote in a recent artwork statement. ‘[These words and images] suggest that if we learn to see the natural world in a slightly different way, we can access another way of knowing and moving.’

But Baker is also clear-eyed about how Indigenous ways of life can be appropriated and exploited for capitalist consumption. The three-channel video installation Bamboo Paradise (2019) takes a critical look at Southeast Asian ‘primitive lifestyle’ content on YouTube, which fetishises and monetises fantasies of preindustrial technologies and lifestyles. The work focuses on a Cambodian channel called Survival Builder, which features elaborate structures in the jungle (think bamboo villas, luxurious treehouses, swimming pools with slides, etc) purportedly built using traditional construction techniques. The work features footage from the channel and interviews with fans as well as the founder, who is revealed to be a man living in Siem Reap. He sources ideas for different structures on Pinterest and YouTube, and employs a group of villagers to construct them in the jungle, creating a disturbing content industry that is built on escapist fantasies of ‘rustic’ village life and ‘ancient’ Asian technologies.

In her more personal works, Baker explores her conflicted relationship with her cultural heritage. Exploring her desire for connection with her ancestral roots and her feelings of alienation is the video Tarun (2020), which chronicles her time spent living in her mother’s birthplace in Sarawak. Throughout the video she has earphones on that play a tape of her mother recounting childhood experiences, her subsequent marriage to a white man and moving to Australia. We hear all these through Baker’s lips, as she apes the words like she is following a foreign language learning-tape. All the while, Baker is portrayed as a visitor: whether lazing around her relative’s rundown house, swimming in a pond with village children or making a traditional steamed-rice dish cooked in bamboo. The video captures the artist’s ambivalent feelings towards her cultural roots – striking a balance between a desire for connection and the inevitable diasporic estrangement from a foreign landscape, language and culture.

Finally, Baker is aware of how the digital world can provide a refuge for Indigenous people and their diasporas. The installation Personal Computer: ramin ntaangan (2022–23) combines computer parts and various other personal objects of cultural significance. We see a custom-made pc housed in a small structure resembling a traditional Bidayǔh longhouse, a raised wooden house made to house many families. There, a computer screen is playing a digital animation of a crocodile on a spit, with a sword in its mouth. Nearby, another monitor screen is placed above a rock made of foam, displaying images of her family home. The work acknowledges how the virtual world has become a vital resource through which Baker remains connected to her heritage: through Internet searches, Facebook groups and family WhatsApp chats. The universe that Baker has constructed here (out of a computer she assembled herself and a minihouse she had hand-thatched) speaks of the rich possibilities of how communities can build worlds to stay connected to their roots and each other – online and offline.

Tiyan Baker is a Malaysian Bidayǔh and Anglo-Australian artist working with installation, photography, video and sculpture. Currently living on the Awabakal and Worimi lands known as Newcastle, Australia, her work centres around her Bidayǔh culture. In 2022 she was awarded the National Photography Prize by the Murray Art Museum in Albury.