The Chinese painter is selected by Martin Herbert as part of ArtReview’s annual spotlight on individuals whose work is worthy of more attention

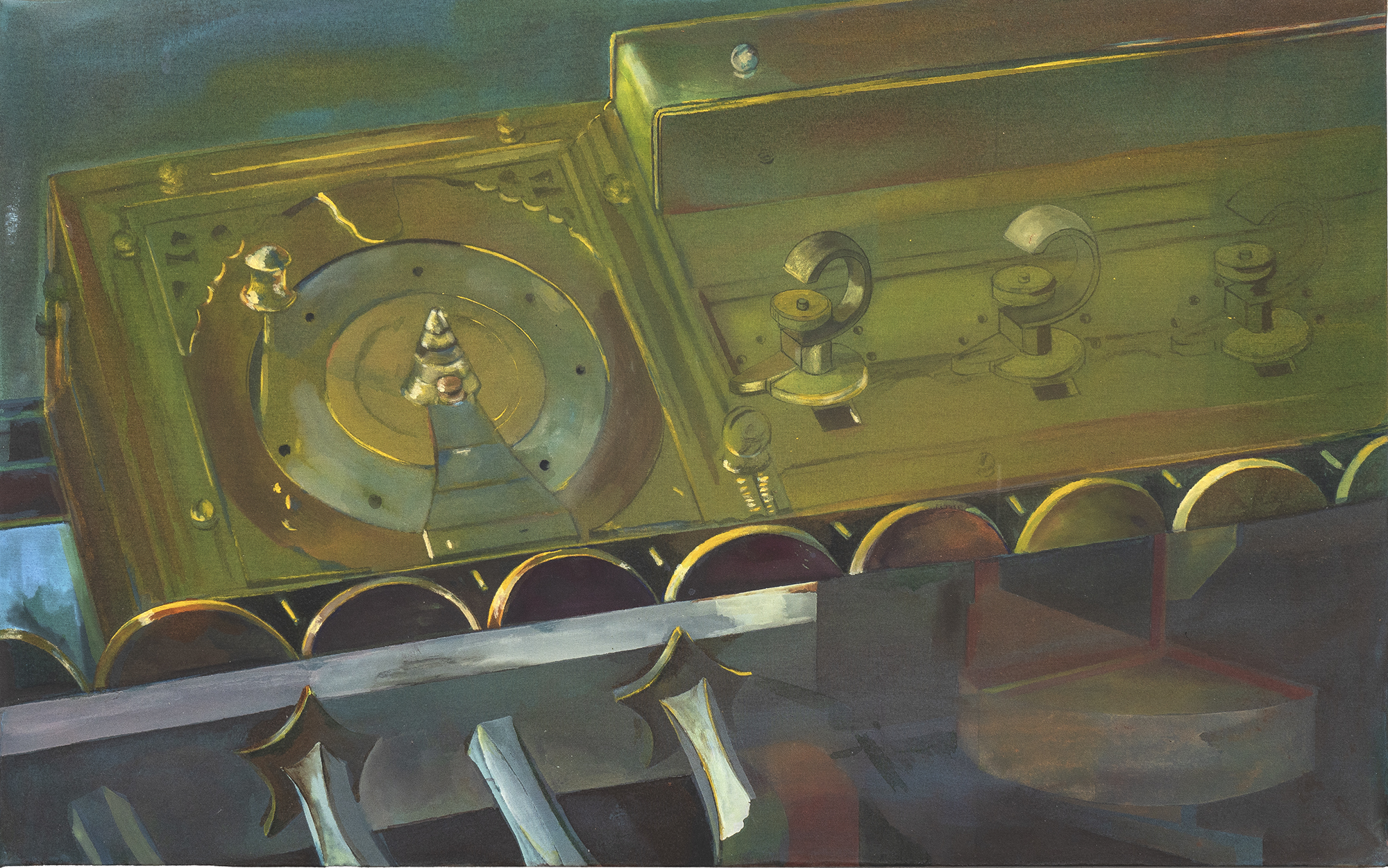

In an era when much contemporary painting is mired in conservative aesthetics and seemingly wants to look away from the present, Leah Ke Yi Zheng addresses herself directly to our digitally addled moment, inventively rewiring the oldest artform to consider the consequences of the newest tech. Admittedly, a viewer might initially think that the Wuyishan, China-born, Chicago-based Zheng is backtracking somewhat into modernity: a painting such as Untitled (2025) is one of a number of paintings (we won’t say canvases, since she paints on translucent silk) that, since circa 2021, have featured pale, ghostly representations of a fusee, a conical spindle integral to antique watches. Yet Zheng isn’t channelling Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp. Machinery here serves as a representable shorthand for the increasingly intangible and upending technologies of today, and offers a long view: it points, albeit without reducing the art to sociological messaging, towards the transhistorical fact that such innovations can entirely alter the texture of reality. See, for example, the beautiful-looking mechanical calculator or ‘stepped reckoner’ in Zheng’s widescreen-format Leibniz’s Machine (2024), developed by German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1694 – a device that would reshape multiple sciences and the world of commerce.

Iconography, though, is just one aspect of Zheng’s bending of painting’s parameters into conversation with the now. Her mahogany stretchers, for example, are rarely precisely rectangular but rather pointedly warped – a way, it would appear, of additionally hitching the subject of technology to conformity and the questioning, or otherwise, of convention. In the wider context of Zheng’s art, this might scan as symbolic pushback. Meanwhile, the cool, stripelike geometric backgrounds of many of her paintings turn out to represent, subtly, hexagrams from the I Ching or ‘Book of Changes’ (which helped inspire Leibniz’s device, placing Chinese divination practices in the background of the development of modern financial practices). Against cold rationality and mechanical behaviours, Zheng counterbalances the operations of chance; it made sense, in a Los Angeles show in 2024, that her East/West-fusing work was placed in conversation with that of John Cage.

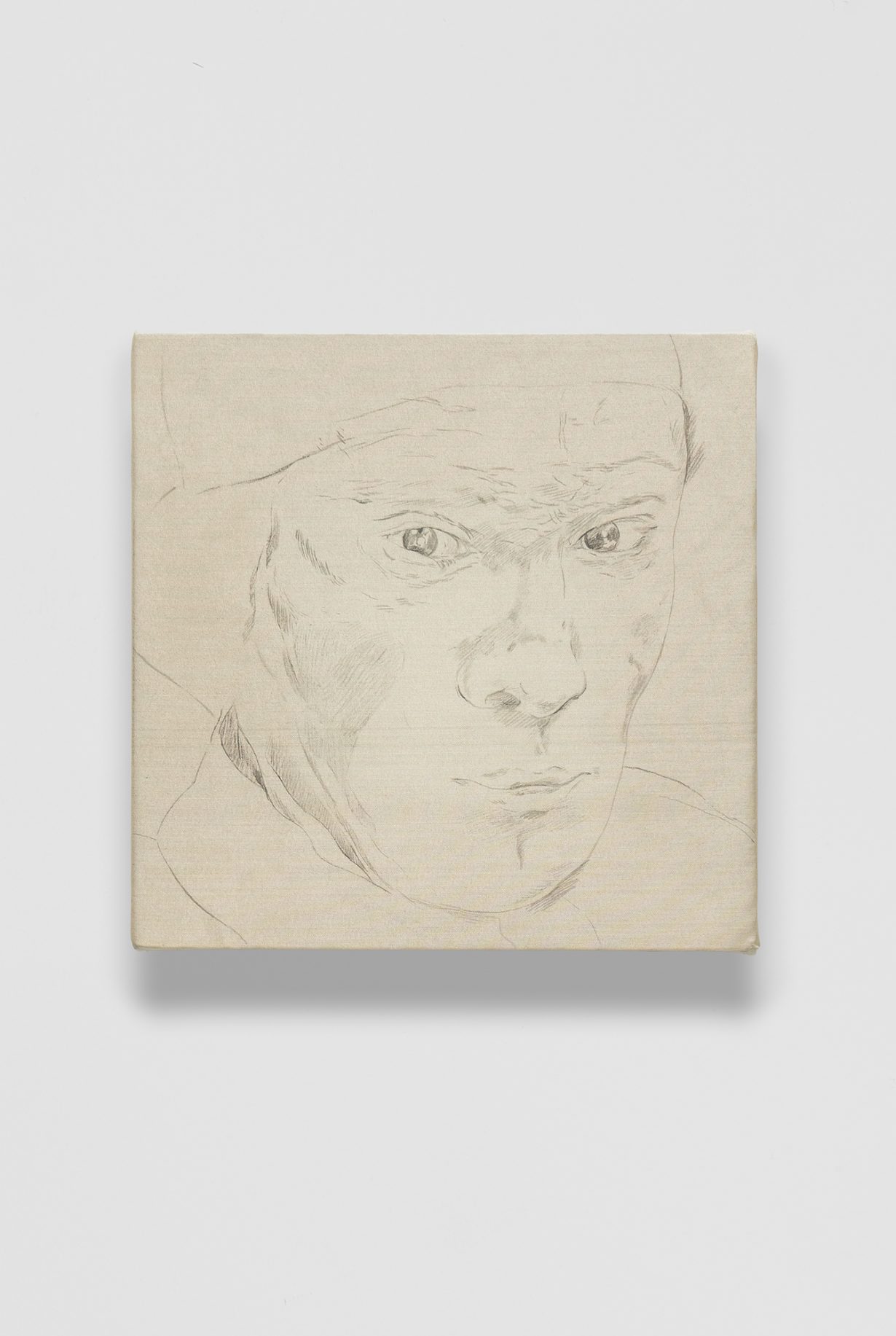

She mobilises chanciness, too, in the ingenious way that she presents her work. That Zheng paints on silk, in the traditional Chinese manner, and then sometimes suspends her canvases so that light passes through them, means that their reception is in conversation with the aleatory play of daylight. They step, to a degree, away from that implicit nemesis of Zheng’s art, control. Meanwhile, a secondary strand of her painting offers up counterpoints to inhumanity: she paints animals (Untitled (Ram), 2023); dancers (Nijinsky, repeatedly); and Father Sogol, a character in René Daumal’s 1952 allegorical novel Mount Analogue. How you align such figures with, or against, the other subjects of Zheng’s art might depend, person-to-person, on your historical knowledge and your inventiveness; you may just experience the subliminal pleasure of being guided back to the warm-blooded world.

That said, Zheng’s machinic paintings never feel cold either,

thanks to her counterbalancing their often near-abstracted subjects

with the delicate pleasures of painting: her subtle, tertiary-rich colorations, her frequent deployment of glowing light. They’re visible in the context of New Humans: Memories of the Future, opening in March at New York’s New Museum, which appropriately explores ‘what it means to be human in the face of sweeping technological changes’, and – signalling that Zheng has arrived at the stage of institutional solo shows – in her monographic exhibition Change, I Ching (64 Paintings) at Chicago’s Renaissance Society. Here, while presenting a cycle – which she avowedly considers as a single work – based on the entire hexagram cycle of the I Ching, Zheng has also covered various windows to emphasise the play of light and adjusted the gallery architecture, making the venue part of the work. As ever, for all that you’ll notice her art’s edges, it never stops at them.

Explore the 2026 Future Greats

Leah Ke Yi Zheng is a Chinese painter based in Chicago. Her work merges techniques of Chinese painting with histories of the Western avant-garde. Her solo exhibition Change, I Ching (64 Paintings) is on view at the Renaissance Society, Chicago, through 12 April.

Selected by Martin Herbert, associate editor, ArtReview