The artist offers a new vision of such spaces that leaves us wondering whether or not such a question could ever become a reality

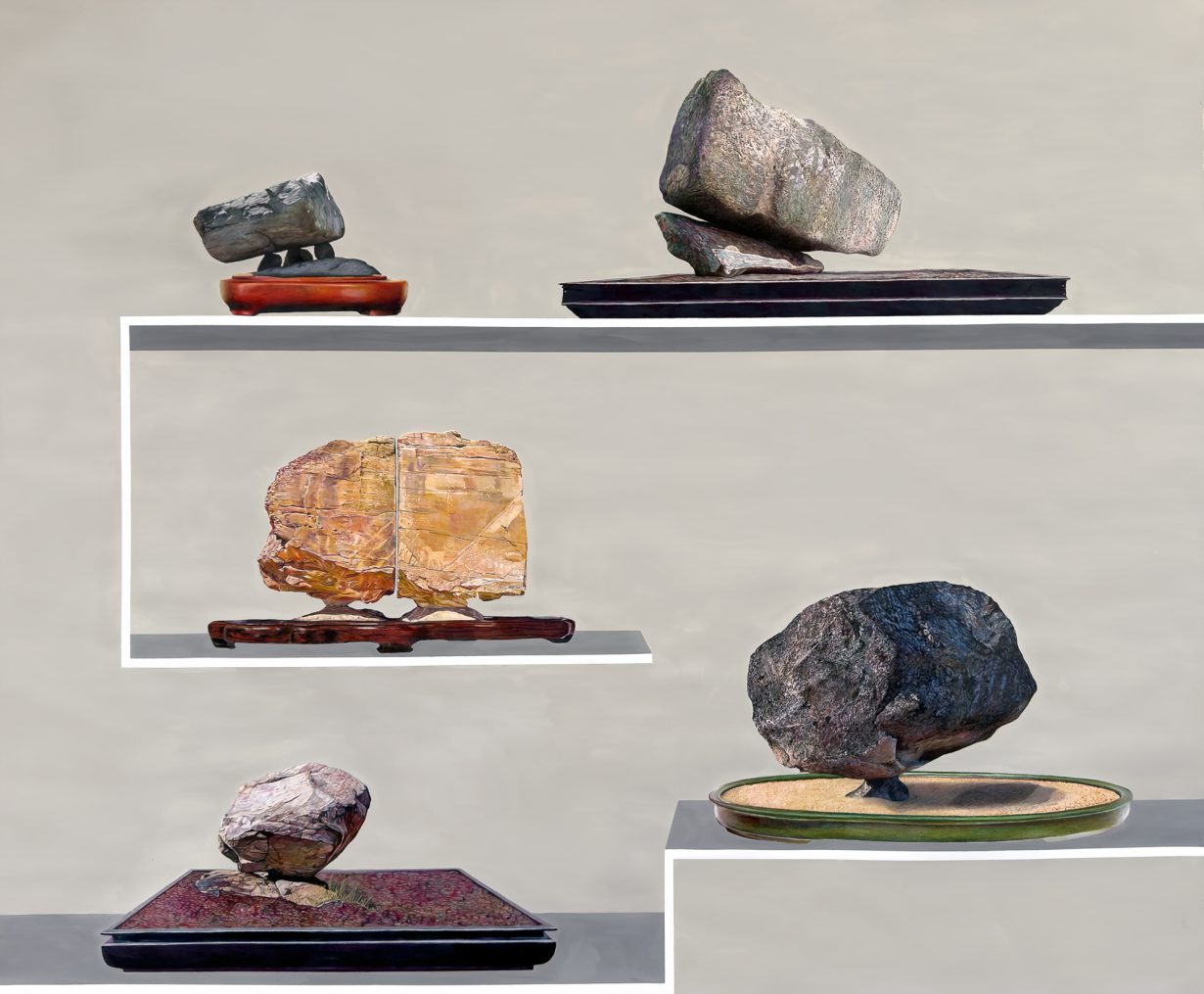

The artist Gala Porras-Kim is making her own museum. On one shelf sits a shallow bowl holding a sand-coloured rock that, if you scrunch your eyes up, looks a bit like the two humps and head of a camel. On a shelf below that is another rock that resembles what might be a slightly melting elephant, and below that again a low tray with a cluttering of grey rocks that appear like the upper half of an eagle, wings spread, about to rise into the air. These rocks exist; the furniture within which they sit, however, is a fiction.

The scene is depicted in pencil and ink as part of the large drawing titled Nine animal shaped stones (2025), currently part of the Colombian-Korean-American artist’s debut exhibition – Conditions for holding a natural form – at Kukje Gallery in Seoul. Each of the stones is an example of a scholar’s rock, selected in this case for their animal resemblance; several other drawings nearby depict similar gatherings, stones that look like famous mountains – from Mt Fuji to the Matterhorn – others that resemble sprouting mushroom caps. Scholar’s rocks sit at the heart of a practice, which originated during the Tang dynasty in China, of displaying and contemplating naturally occurring stones, that later developed into divergent strands in Japan and Korea. It’s a classic example of humans projecting onto inert matter, imposing meaning where there was none. Each of the rocks that have made it into Porras-Kim’s works is part of an actual collection housed somewhere in the world. As such, each is evidence that someone, somewhere, decided that a particular aggregate of minerals was worthy of saving and savouring in perpetuity. Porras-Kim, in turn, has gathered their likenesses, neatly representing them as a new, impossible sort of collection, a collection made from other collections, and a mini, two-dimensional museum describing how humans project meaning onto the world around them.

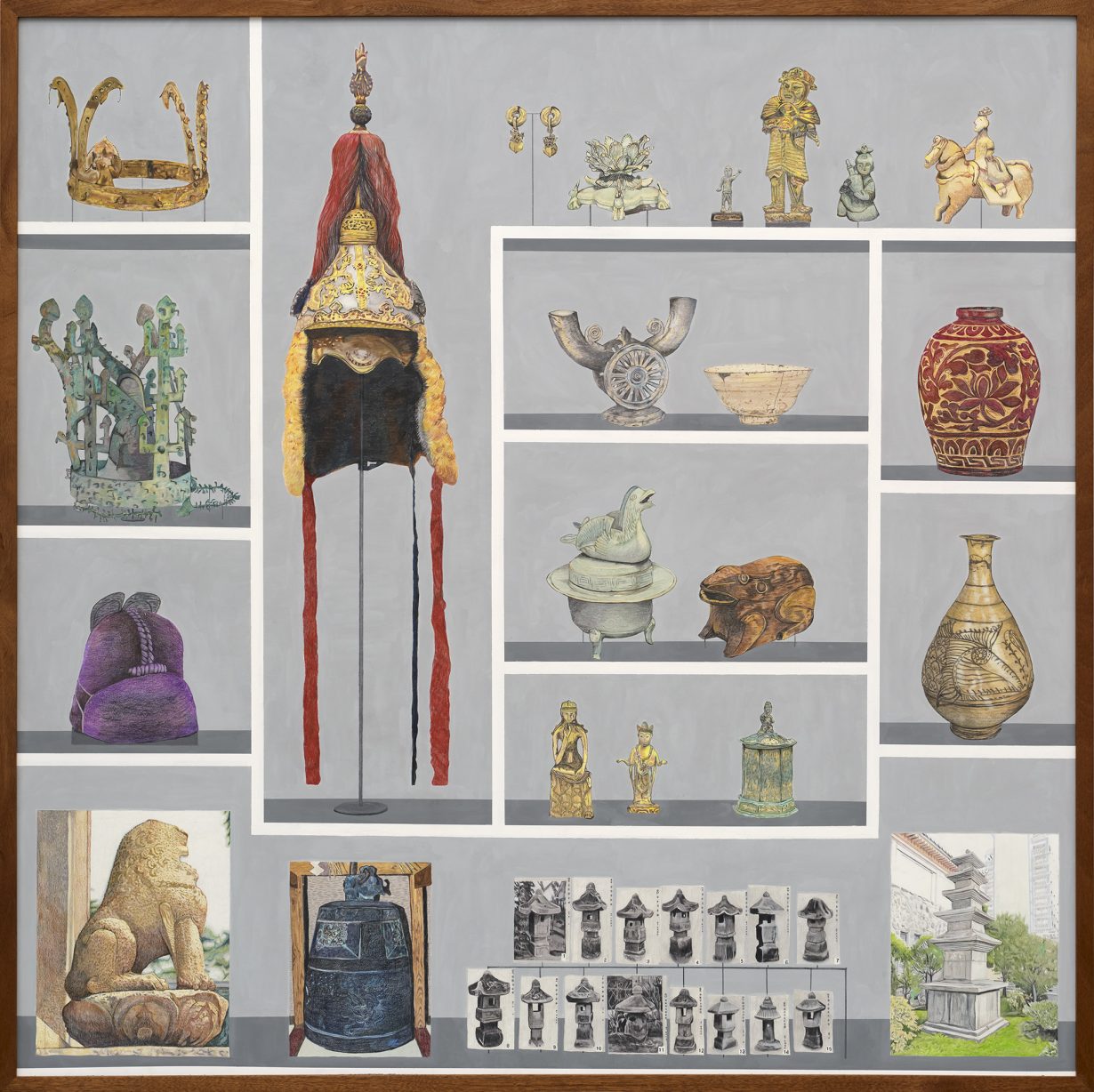

In a long-running series of similar drawings, the artist recreates and reorders the holdings of various institutions onto boxy shelving arrangements, as in 51 Snuff Boxes at Carnegie Museum of Art (2025) or the four panels of 530 National Treasures (2023), which gathers together miniaturised depictions of officially designated ‘treasures’ from across the now divided North and South Korea (the treasures were originally designated before the separation and under Japanese occupation): chairs and vases, alongside snapshots of buildings and statues, all drawn to be neatly arranged on long, even white shelves. These drawings offer a taxonomical survey of collections, sometimes simply offering a museum’s own rationale up for scrutiny or, more often, re-presenting and re-arranging them by size or type based on Porras-Kim’s own made-up display system. They seem to suggest that we might find other logics for each collection, finding alternative associations between objects; but they also have a detached sense of omnipotence about them, as if we are being invited to survey the surveyors. These realistic drawings also have an uneasy materiality: less factual than any photograph of the original objects, but still indexed to the thing itself; more mediated than any attempt to just replace the physical objects in front of us. That unease about what we’re seeing in front of us tugs at a persistent question running through the work – one nudged further when such work is displayed in a commercial gallery, outside of the institutions towards which much of her critique is addressed: for whom is she making this sprawling, quasi-fictional museum?

Porras-Kim’s broader oeuvre proposes a type of gentle institutional critique, with installations and conceptual insertions that aren’t seeking to demolish or replace the museum as an entity; rather they attempt to reconfigure its hierarchies and organisational logics. Her work addresses the peculiar ways in which historical objects have been classified, displayed and organised, and how that, as a result, has limited and proscribed our own understanding of the objects, ourselves, and the world. The letters to curators and directors that often appear as part of her work suggest alternative, sometimes hokey, ways to approach institutional holdings, like requesting, straight-faced, that the Director of the National Museum of Brazil conduct a ritual cremation of the remains of ‘Luzia’, the human fossil in their collection. Other drawings are designed to be viewed and appreciated more by the entities held within the collection themselves, such as Sights beyond the grave (2022), which depicts an empty, rocky landscape, designed to wrap around a British Museum vitrine containing a funerary statue of the ancient Egyptian mayor Nenkheftka. The drawing is designed to offer him a comforting view of home, while, in reality, he sits on a plinth in London surrounded by hordes of ravenous tourists. In her gesturing to ways by which museums might move out of the binds they have created, Porras-Kim seems to be interested in steering existing institutions towards a time before the professionalisation of the sciences, to an age populated by wunderkammers and natural philosophy, where spiritual endeavours and scientific inquiry were intertwined and indistinguishable. Most often, though, her suggestions remain just that, and so seem geared more towards a speculation not about what a museum is, but about what it could be – whether in our future or perhaps another.

Polish historian Krzysztof Pomian, in his book Collectors and Curiosities (1990), optimistically described museums as ‘meeting-places where the social fabric can be rewoven’. He dedicates a chapter of the book to ‘the visible and the invisible’; the invisible of the museum collection is firstly a literal one: all that is not part of the collection, outside of its walls, beyond its remit, or deemed not worth collecting. Closer to home, the invisible is all that is part of the collection but remains in storage, in a warehouse on the outskirts or tucked into a basement drawer. At one point in the chapter, interestingly, he writes that funeral objects and offerings should be considered collections in themselves, because there is an ‘acknowledgement of the existence of a potential audience, in another temporal or spatial sphere, implicit in the very act of placing the objects in a tomb or temple. This is the belief,’ he asserts, ‘that another kind of observer can or does exist’. Porras-Kim’s suggestions, replacements and insertions draw on all these senses of the invisible museum, and seem inclined towards acting on this belief, working towards a wider range of potential audiences – to audiences that might not be human, or even alive.

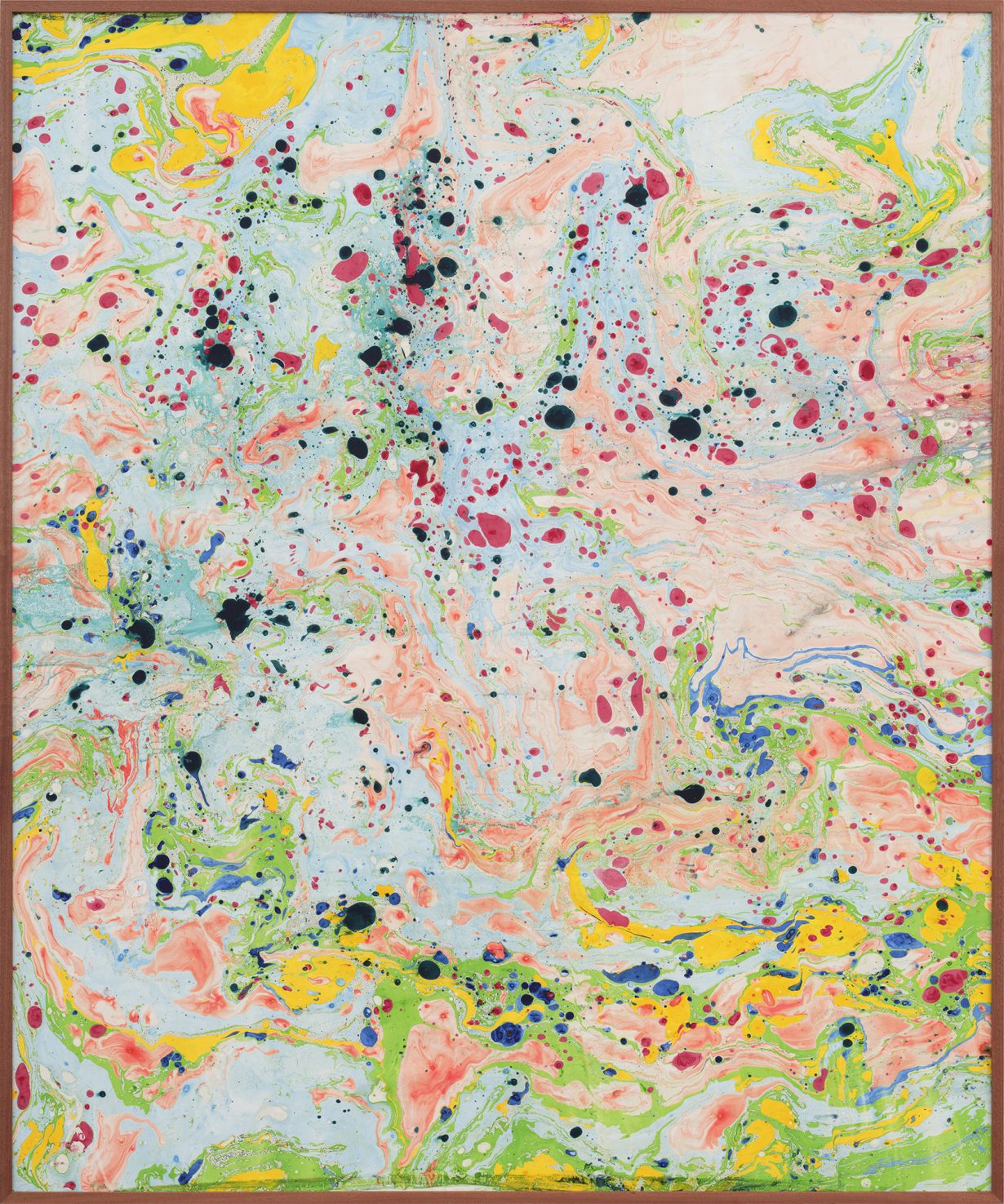

In a letter to the director and curator of the Gwangju National Museum that accompanies the drawing A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2025), Porras-Kim points out a central paradox of a museum holding human remains, in that ‘institutional interests may pose a conflict should the remains be allowed to completely decompose as would be their natural course’. The institution, according to its own precepts, must preserve its collection; a stance which places it at odds with the forces of nature – entropy, decay, dispersal. As if, within its walls, time stops and the atoms and elements that make up the objects of its collection are stilled. The large drawing next to the letter is filled with swirls of light pink, baby blue and neon green, splotched with darker blobs of blue and red, part of a series in which Porras-Kim uses ink in the same manner as paper marbling to conduct ‘encromancy’ (ink divination), through which she asks the mortal remnants in various museums where they might like to be buried. The resulting archipelagos and eddies are fictional maps, or, at best, offer directions that the living are unable to follow.

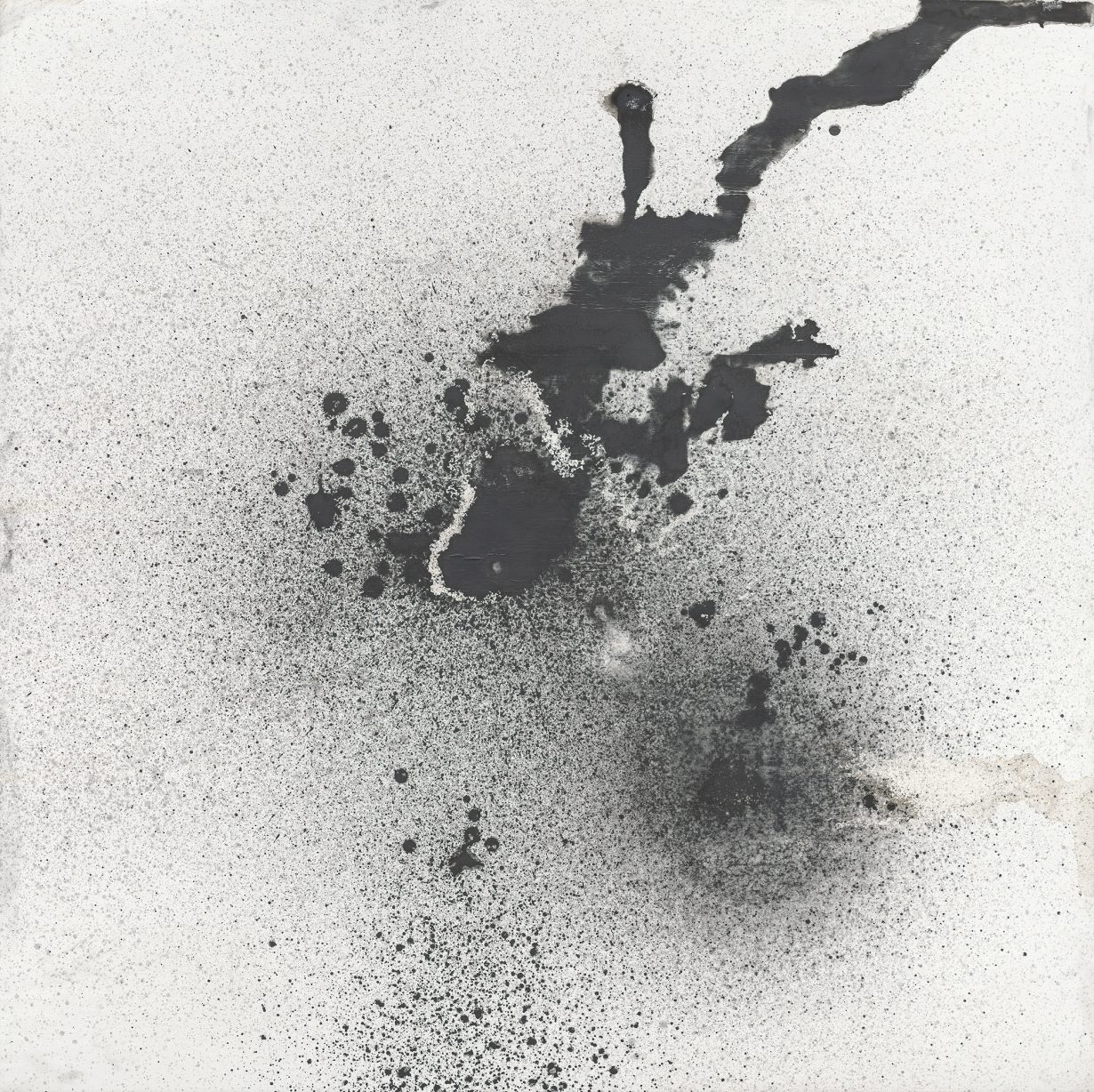

A parallel act of divination has taken place across the artist’s Forecasting Signal series. Across various galleries over the past few years the artist has installed a dehumidifier that feeds water collected from the exhibition air up to a graphite-imbued sheet of fabric hanging from the ceiling. The collected moisture eventually drips back down onto a white panel on the floor. The resulting institutionally penned drawings are hazy black-and-white compositions, at times looking like lazy abstract-expressionist drip paintings, at others like enlarged close ups of X-ray scans of, say, someone’s hip. Under the title Signal, a handful of such panels from museums in Cleveland, Denver, LA, Mexico City and Seville are included in the Seoul exhibition, displayed without the contraption that produced them. What’s left is an indication of each building’s moisture levels, sure; but they also feel like attempts by each space to communicate. A kind of architectural Rorschach test, where we might be able to read into the pencilled bursts and blobs what, for example, the Modernist bunker of the MAK Center in LA wants, spattered instructions of what it might like to take place within its trim white walls.

Accompanying the rock drawings in Conditions for holding a natural form is another collection, a huddle of rocks on a low plinth, each of which was donated in response to an open call in Seoul for people’s own scholar’s rocks. Some are small, smooth menhir-like shapes; others more craggy and unlike each other, while one has white, flower-like shapes blooming on its polished surface. Some, accompanying notes inform us, are reminders of a particular time or place, others a keepsake from a grandparent. The intimate projections that take place in each rock run parallel to those in the drawings; each testifies to the fact that, at heart, someone, somewhere found meaning and decided to hold onto it. The exhibition places the rocks and rock drawings in conversation with the Signal drawings: the random shapes of the stones are imbued with abstract human associations; the abstraction of the building-produced drip drawings seem to be awaiting such a potential observer, who might yet make similar interpretations. Between these works, and her wider collections, Porras-Kim suggests an absent museum in which, ideally, such emotional investments can happen on a spectrum beyond the anthropocentric ones we’ve implicitly agreed upon. Porras-Kim’s museum might be a meeting place, but one in which the social fabric is unwoven, made abstract and more malleable, and less human.

Conditions for holding a natural form is on show at Kukje Gallery, Seoul, 7 September – 26 October