The Los Angeles-based Iranian filmmaker opens up a brave new world of contemporary storytelling

In late October last year, a neon-yellow envelope came through my letterbox. Inside was a thick black card embossed with the sentence, ‘The gradients of fascism are diverse in their predictable dullness’. On the other side was a business-card-size USB drive, printed with a patchy green pattern of what might be an ivy-covered wall, punctuated by a figure covering their face with a black-and-white mask printed with the features of director Pier Paolo Pasolini. The sentence and the image both appear in the nine-minute film contained on the drive, Men of My Dreams (2020), by Los Angeles-based Iranian artist and writer Gelare Khoshgozaran. It’s a patchwork of dream impressions and pointed observations, opening with a passenger’s view of a drive down a street in LA. Armoured vehicles and rubbish trucks line the road, while shopfronts are graffitied with ‘ACAB’, ‘BLM’; a bank on one street corner has ‘George Floyd’ written across its window. Subtitles describe the artist’s move from Iran to the city years earlier. ‘I miss my home, but everywhere is so ruined on this planet I feel at home anywhere.’ What follows is a set of a vignettes, the artist sporting a range of masks depicting the titular men that appear in her dreams: poet Federico García Lorca, singer Farhad Mehrad. In one scene, she sits by the sea holding a mask of theorist Edward Said in front of her face, her hand covering his mouth as if stifling a giggle. In another, she mimes playing a game of tennis, the mask she wears remaining an unidentifiable blur.

The mailout was part of London gallery Cell Project Space’s monthly postal series, Queer Correspondence, which ran from June to December last year. Khoshgozaran had initially been scheduled to have an exhibition there; it’s been postponed to this year. The USB key’s delivery was intriguing, like a stylish invitation to some cryptic event; though it was also, at that point in the year, a relief to be able to watch an artist’s film without yet another live-streamed event or time-limited screening (and the resulting guilt of having missed it entirely). In Khoshgozaran’s fractured, unfinished dream diary, where the aftermath of protests is placed next to serene seaside moments, the evocation of these figures seems to point towards a desire for escape, from the ruin, the virus, the violence – and to look to them for answers or comfort. But no resolution arrives, we just hear the persistent hiss and click of a vinyl record reaching the end of its spiral. While tapping into the isolation and malaise of the pandemic, Men of My Dreams’s tone and delivery carries many of the themes that run throughout Khoshgozaran’s films, essays and installations: a lyrical sense of dislocation and unease, where things remain unfinished, unresolved, and where political events are mapped unevenly onto intimate thoughts and daily life.

While much of Khoshgozaran’s work begins with documents and documentation – state memos, journalistic photographs, 16mm footage of landscapes – these teeming facts and places become displaced and misplaced. That the arid Southern California climate where she is based is similar to that of Iran is a source of ambivalent nostalgia; a wistfulness lined with hard irony in finding reminders of home in a country that continues to punish Iranians with years of sanctions. In the 30-minute film Medina Wasl: Connecting Town (2018), a set of voices speak over a desert scene. They describe “a giant expanse of bright sand”: “It was flat and brown, and a dust storm came and it looked like something out of a movie”. It becomes apparent that these are soldiers, recounting their sensory experiences of excursions into southwest Asia, where we assume, at first, that what we’re seeing is located. Then buildings appear looking oddly blocky, becoming apparent as shipping containers that have been hastily painted to look like they’re made of mud bricks. An abandoned street has stalls stocked with plastic fruit and fake eggs. Khoshgozaran’s notes accompanying the piece explain the unsettling facade: this is a military training facility in California, designed to prepare and acclimatise troops to some projected version of what they might encounter in Iran or Afghanistan. As we continue to tour its ersatz butchers and mock mosques, the image is overlaid with another screen that shows a Google Map scrolling along the southern border between Iraq and Iran. We are directed to look at, feel and smell the Persian Gulf, but remain rooted, unsteadily, on the West Coast of the US. At one point the artist appears dressed as an Iranian soldier, running towards the camera through a grove of date trees, and then hesitantly dancing, turning the terrain of simulated battle into an absurd and mournful cosplay. The histories of military and economic actions and lives that drift in their wake, Khoshgozaran suggests, create a tangle of echoes and correspondences that reverberate long after, bobbing somewhere between fantasy and hard fact.

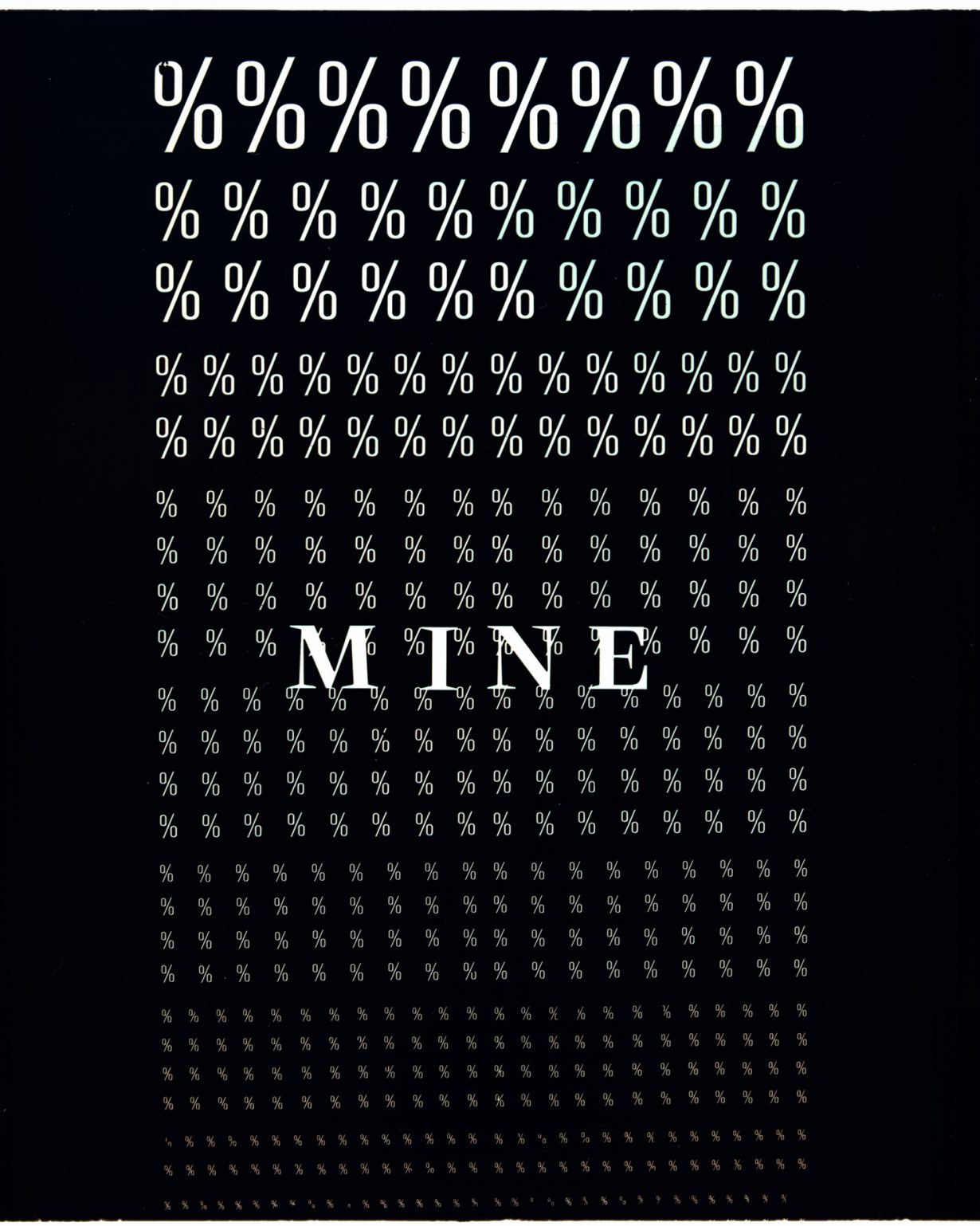

In Medina Wasl, the simplified topography of Google Maps represents the date palms growing on the shore of the Shatt al-Arab river as a generic light green, the map layered by Khoshgozaran with imagery of date palms in California. Each is a different way of seeing landscape, each with its own limitations – it is the edges and ellipses of these forms of knowing that Khoshgozaran seems intent on tracing. Likely Mine, her exhibition at the Visitor Welcome Center in LA at the start of last year, revolved around different types of looking and surveillance. The floor of the gallery was spread with neat rows of model-plane parts, while nearby were several lightboxes holding Compositions for X-Ray Machine (2020), a set of inverse collaged images of overlapping keyboards, model planes, a customs declaration slip. Hanging above them, the video Likely Mine (2020) is mostly black, dotted with occasional lighter specs, until points where the screen fills with a pixelated hash of pinks, greens, purples and blues: the visible effects of electromagnetic radiation when the artist’s phone was put through airport security scans. Air travel might have become severely limited since then, but at its core the show seemed more concerned with making visible and apparent the routine incursions and probes we have come to normalise, the multicoloured static its own map of the ways security checks, body scanners and aerial photography touch each of us.

Visitor Welcome Center, Los Angeles). Photo: Josh Schaedel

At the entrance to Likely Mine, a voice from a cassette tape player enunciates a set of phrases towards a small centrifuge sitting adjacent on the floor, each one apparently the headline from a news item that contained the word ‘centrifuge’. At that point last year, the word was in the news frequently in relation to the Iranian government’s announced plans for its nuclear programme. But in Reading the News to Waco (2020), as this work is titled, an algorithmic search for the word spits out all kinds of results: “Five strategies for delivering complicated technical training”; “Why extra virgin olive oil is the healthiest fat on earth”; “Trump faces foreign policy challenges”. The casual collision of the mundane, the political and the digitally-delivered accidental is telling; or rather, it is an accurate portrayal of the terrain that Khoshgozaran suggests we already inhabit, a place where the three are connected and confused. There is a thread through her work that suggests life is prescribed by the military-industrial complex, determined by its persistent machinations. But as with the title of Likely Mine – punning between admitting ownership and the presence of a potential explosive device – and the expectant gaps between the various works in the room, the confusion and the dream state seem a way to navigate such confines.

Through its levelling of fact and its attendant fictions, of dream and protest, Khoshgozaran’s work enacts a particular form of contemporary storytelling: wary of the essay film’s tendency for narration, which enacts a simplification or occlusion of sorts; but one that is equally wary of documentary’s voyeuristic and othering tendencies, what writer and filmmaker Fatimah Tobing Rony has called ‘fascinating cannibalism’. It is dispersed, subjective documentary that follows on from the work of practitioners like Trinh T. Minh-ha and finds echoes in contemporaries like Ana Vaz and Rehana Zaman. Khoshgozaran attempts a destabilised, critical and oneiric pulling away from the photographic document, mapping the effects on the mind of the globally dispersed forever war, and asking where we might go from here. In Men of My Dreams, the video ends with a quote from Pasolini’s The Decameron (1971): ‘Why complete a work when it’s so beautiful just to dream it?’ It then cuts back to a shot of the sea, low, foamy waves pawing at the rocks that line the shore. The dreamer is, yet again, the activist of our time. ‘Crisis time is not work time,’ as Khoshgozaran wrote in article from August last year, ‘but there is a job to be done: to dream and make plans for their coming true.’