The artist proposes an expanded theatre where light is the principal performer

In his lecture series The Empty Space (1968), theatre director Peter Brook argued that the only ‘interesting difference between the cinema and the theatre’ was that cinema ‘flashes onto a screen images from the past’, whereas theatre ‘always asserts itself in the present’. Unconvinced by this restrictive distinction, avant-garde filmmakers during the 1970s reduced cinema to its barest elements – plain washes of light projected across space – to push against the perceived limits of the medium. Germaine Kruip’s A Possibility pulls from these experimental practices, particularly Ken Jacobs’s concept of a cameraless ‘paracinema’, to propose an expanded theatre that recasts light itself as the principal performer, present and expressive as any actor.

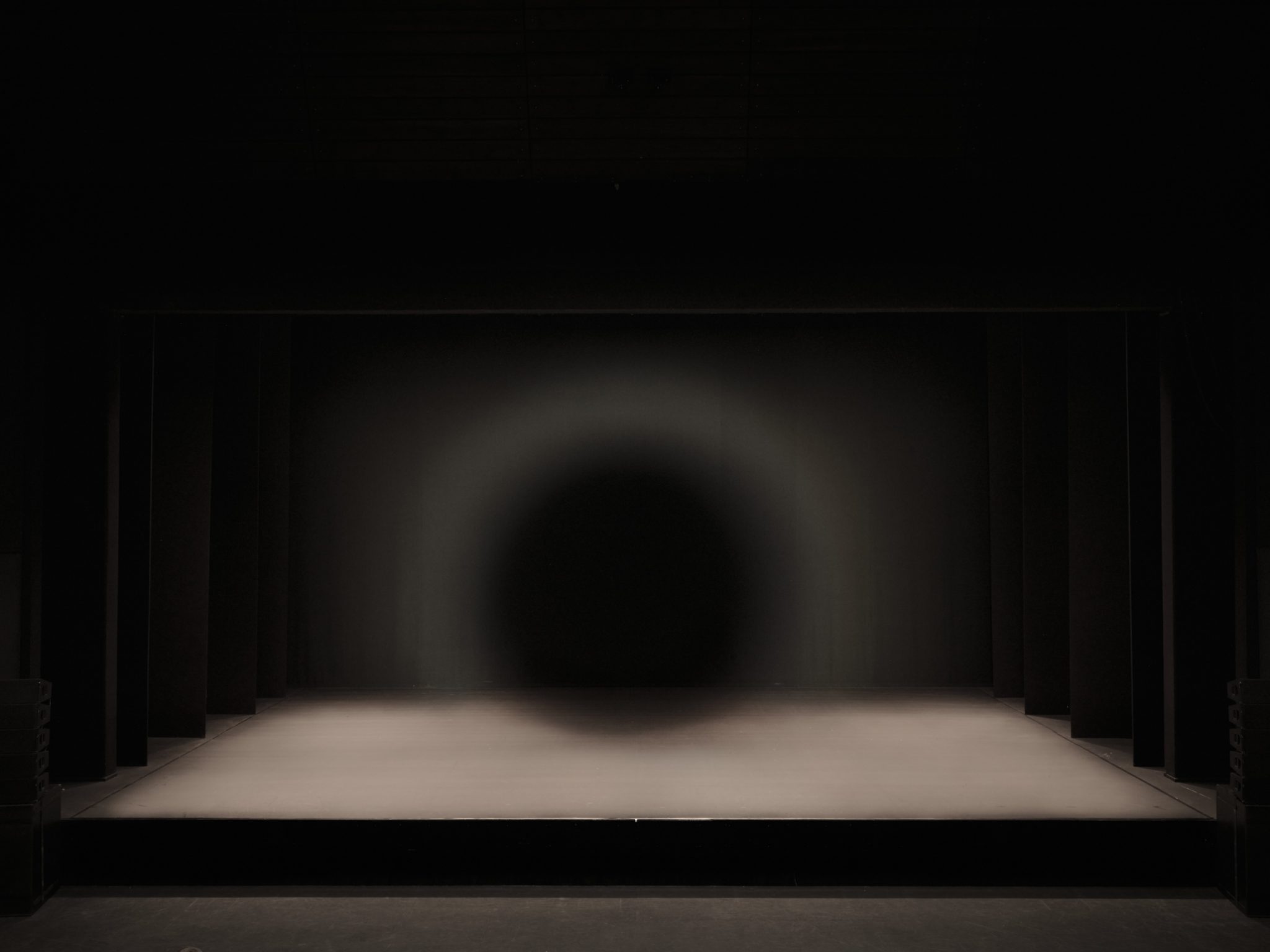

Staged in a theatre at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, just down the road from where Brook’s first lecture in the series was delivered, A Possibility is split into two acts. The first, which involves no performers or props, is ushered in by a ring of white light rising onto the backcloth as stacks of speakers fizz with the white noise of Hahn Rowe’s score. The houselights dim and rise in waves, drawing attention away from the empty stage and into the large auditorium. A rectangle the size and shape of a cinema screen flickers like a film strip, recalling the black and white bars of Lis Rhodes’s seminal Light Music (1975), a work that invited the audience to become performers in a refigured, participatory cinema. As the speakers blast foghornlike drones, a tremulous disc of light is overlaid with wavering shadows until it resembles mist rolling across a full moon, conjuring the gothic imagery of phantasmagoria, cinema’s haunted precursor. When a blinding flash engulfs the theatre, the audience lets out a collective gasp.

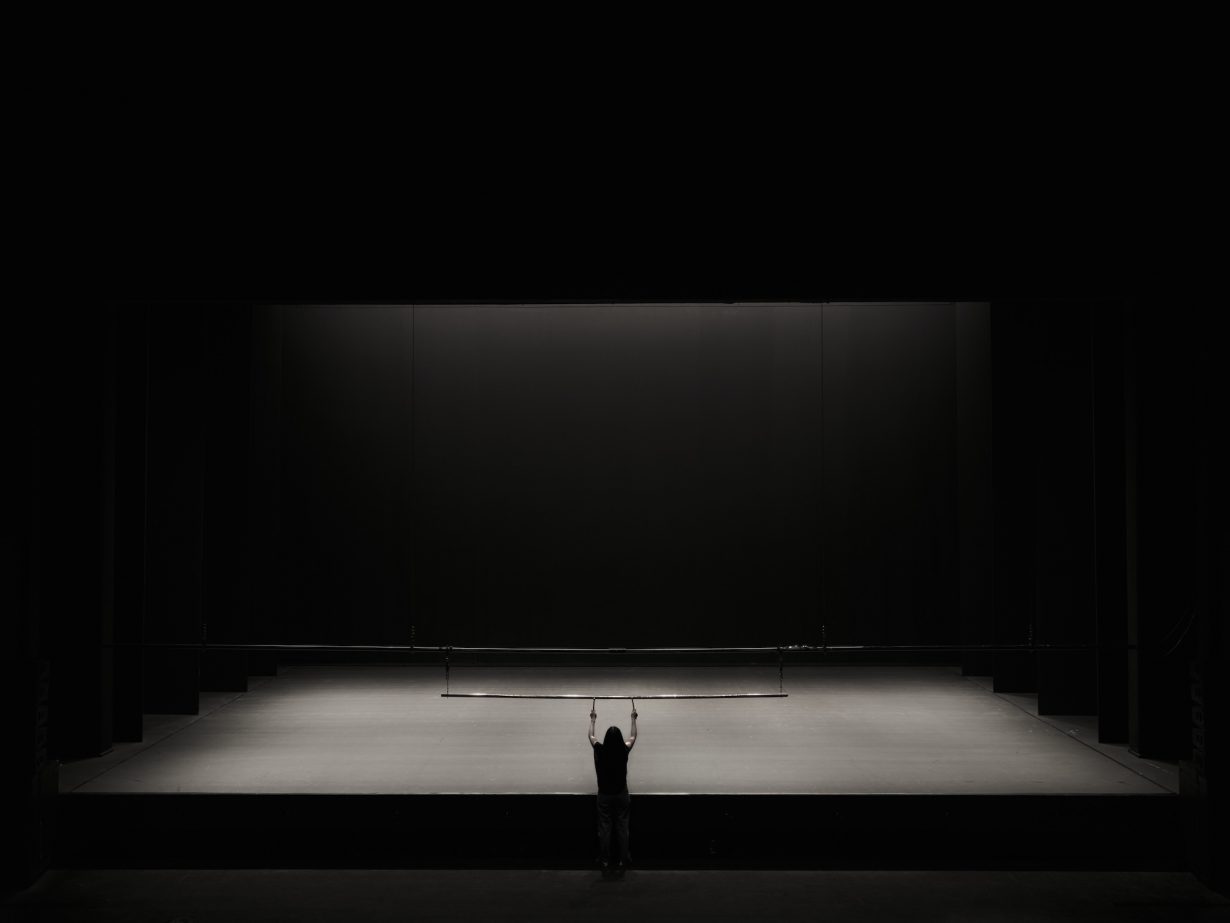

The mesmerising light displays take a backseat in the second act, which involves four performers using beaters to ‘play’ a set of long bronze tubes hung from the ceiling on steel cables. These simple sculptures, designed by Kruip alongside instrument manufacturer Thein Brass, glisten in the light, although the dissonant tones they produce are most effective when the space is entirely darkened and their shrill reverberations fill the cavernous room. Ascending and descending in different combinations, the sculptures are struck with intertwining rhythms alongside co-composer Emily Howard’s prerecorded string-based score. As the tubes are raised for the penultimate time, the backcloth rises with them, revealing the backstage area in all its organised chaos: props, shelves, chairs, trolleys, winches, a wooden broom. Like the pulsating houselights in the first act, through this gesture Kruip presents the theatre as a structure that encompasses yet exceeds the focal point of the stage.

The furore over the recent West End restaging of musical Evita (directed by Jamie Lloyd), whose most famous number is sung from an external balcony to freeloading pedestrians while ticket holders watch a livestream inside, provokes genuine questions over the stability of theatre’s inviolable core: the unmediated ‘presence’ of actors on a stage. Now that screens no longer only show ‘images from the past’, previous definitions that held film at an arm’s length from the immediacy of theatre no longer hold, and Kruip’s work patiently explores possible approaches to the empty stage. Using a limited arsenal of materials, A Possibility openly draws from histories of experimental cinema in order to reconsider the space of the theatre from the ground up.

A Possibility at Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester International Festival 2025, 17 July – 20 July