Giselle Beiguelman’s Botannica Tirannica at Museu Judaico de São Paulo explores scientific research as an expression of imperial power

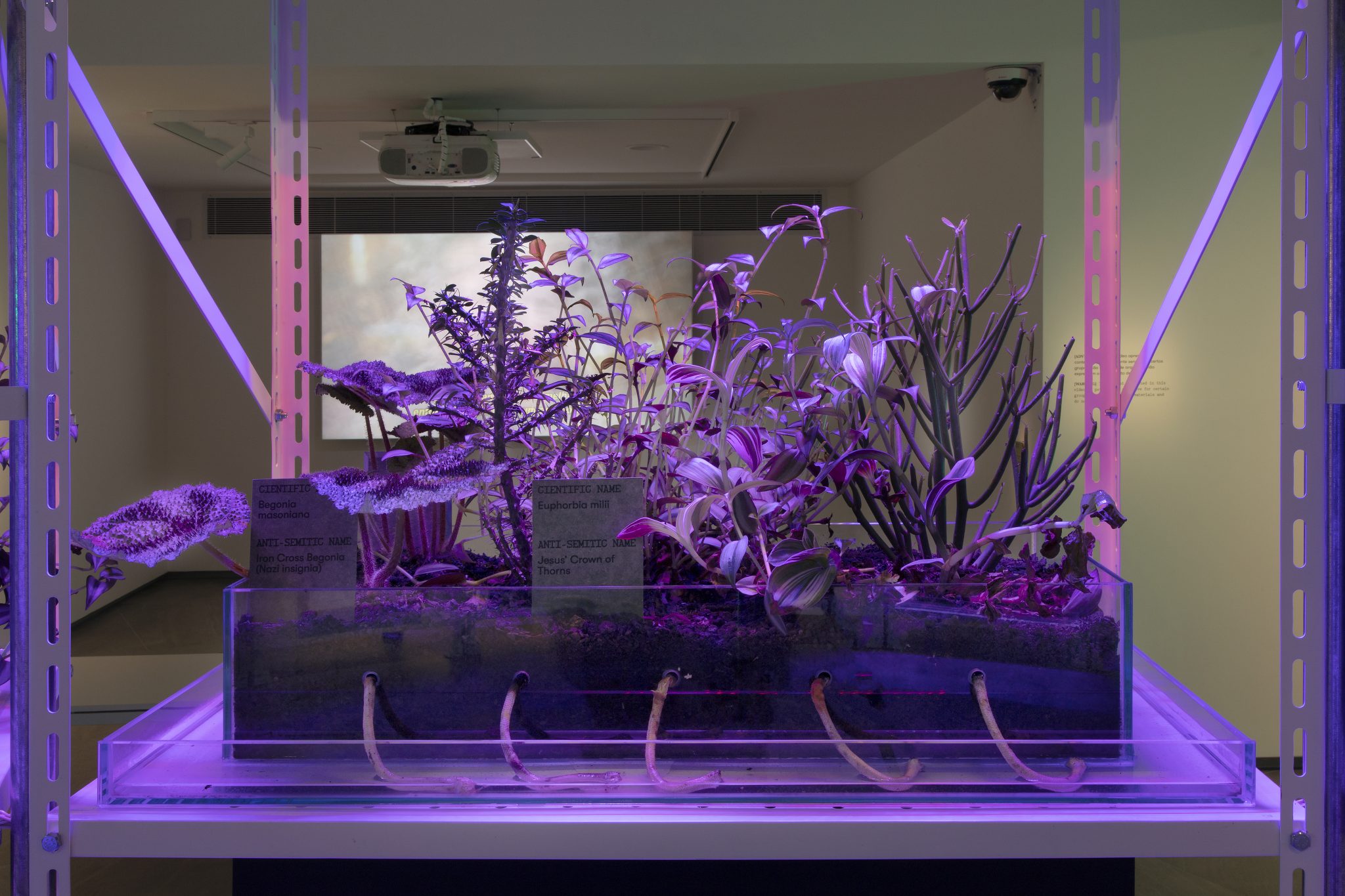

Outside the deconsecrated 1930s synagogue in which the Museu Judaico de São Paulo opened last year, Giselle Beiguelman has planted a garden of weeds. ‘Weeds’ of course is an entirely subjective term, denoting any unwanted wild plant. Inside the building, in front of windows overlooking the exterior beds, the artist provides a ledger, identifying each species with its Latin name and its common name in Brazilian Portuguese (with an English translation). Among them: Wandering Jew (Tradescantia zebrina), Gypsy Braid (Senecio jacobsenii), Jew’s Thorn (Euphorbia tirucalli), Lady of the Night (Cestrum nocturnum). Inside the rotunda gallery, other shrubs and greenery, each with names similarly referencing specific groups of people, grow inside tanks installed on a central circle of metal shelving units. Those historically labelled with anti-Semitic references were invariably ‘invasive’ species – a trait that can be found also in the common names for plants in English and other languages – prone to take over a garden where the green-fingered were not careful to control them. Botany as a site for anti-Semitic prejudice. Other plant names nod to physical caricatures. In Brazil the ornamental Thunbergia alata flower, with its big wide yellow petals that conjoin in a dark central hole, is known as the ‘Mulatto girl’s bottom’ (‘mulatto’ refers to people of mixed African and European ancestry); the tangled climbing vines of Muehlenbeckia complexa is referred to as the ‘Cabelo-de-negro’ (‘Hair of a Black Man’). This caricature of the Black body summons up histories of exoticisation and slavery.

The offensive nomenclature of botany is merely symptomatic of prejudice passed through generations. To this Beiguelman adds questions of colonialism through a series of botanical drawings of similarly offensively named species, hung on the surrounding gallery walls, the medium recalling the adventures of colonial-era botanists whose research was as much an expression of imperial power as it was scientific curiosity: to name and categorise is to give yourself the structure to govern and rule. The subsequent exploitation of the indigenous plants is signalled in a collection of seeds and herbs derived from plants that proved to have economic value; the dehumanising names (a jar of Brazil nuts labelled with an old name employing the N-word; a pot of ‘kaffir’ lime leaves) a means of legitimising exploitation. Yet Beiguelman’s concerns go beyond the legacies of historical prejudice via a series of AI-generated videos, playing out looped on monitors that sit alongside the plants on the metal racking. The videos feature pictures of ‘Frankenstein’ plants created by algorithms that combine images automatically gathered from the internet (one video, showing a woody-looking fantasy species, takes images of plants that slur indigenous groups as its source material, another images of plants with sexist names and so on). Machine learning, built on datasets steeped in inherited prejudice, Beiguelman suggests, will only perpetuate that thinking. As AI is increasingly used in everything from job applications to crime prediction, there are risks of far more serious consequence than the language of the flower bed.

Botannica Tirannica at Museu Judaico de São Paulo, through 18 September