The Berlin-based Portuguese artist on mixing history, theory and performative practice to reveal what has been hidden

Berlin-based Portuguese interdisciplinary artist and writer Grada Kilomba published Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism in 2008 for the International Literature Festival. Now reprinted in its sixth edition, the book examines, via a psychoanalytic lens, the methods used to dehumanise and oppress Black people throughout history. Tracing these roots and foundations from the Atlantic slave-trade-era (the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries) and opening with a statement on the ways in which Black people have been silenced, othered and ultimately rendered subhuman by the white ego, Kilomba takes as a starting point an 1818 engraving of a slave – believed to be the figure of Escrava Anastacia, who became a symbol of catholic devotion in Brazil, and who is depicted wearing a muzzlelike ‘mask of punishment’ – breaking down (in short subheaded sections) the ways in which the white-supremacist ideal established itself as universal thought. Philosophers, psychiatrists, educators, activists, writers and poets (including Frantz Fanon, Gayatri Spivak, Paul Mecheril, Audre Lorde, bell hooks and many more) are introduced along the way, guiding the trajectory of Kilomba’s writings, which deftly slip between academic reference and theory, a more literary and poetic style of prose, and interviews with women who reveal their experiences with everyday racism and microaggressions in Germany, with a clarity that is as accessible to the layperson as it is lucid in its unpicking of the human psyche. Ultimately, Kilomba lends a hand to the reader, patiently illuminating the way through the lasting impacts of colonial trauma and emerging on the other side, to present the possibility and hope of decolonising the Black subject.

The hybrid style in which Plantation Memories is delivered parallels Kilomba’s practice, which has seen her move from roles as a university lecturer and guest professor in the gender studies department at Berlin’s Humboldt Universität, to producing a theatre series titled KOSMOS2 (2015–17, for which Kilomba invited artists who were forced to leave home as refugees to engage in a performative intervention at the Maxim Gorki Theatre), before shifting into contemporary art, where she works primarily with film and installation – a platform to which she has been able to bring together her core interests in theory, performance and literature to engage in discourses around trauma, the history of colonialism, memory, gender and race.

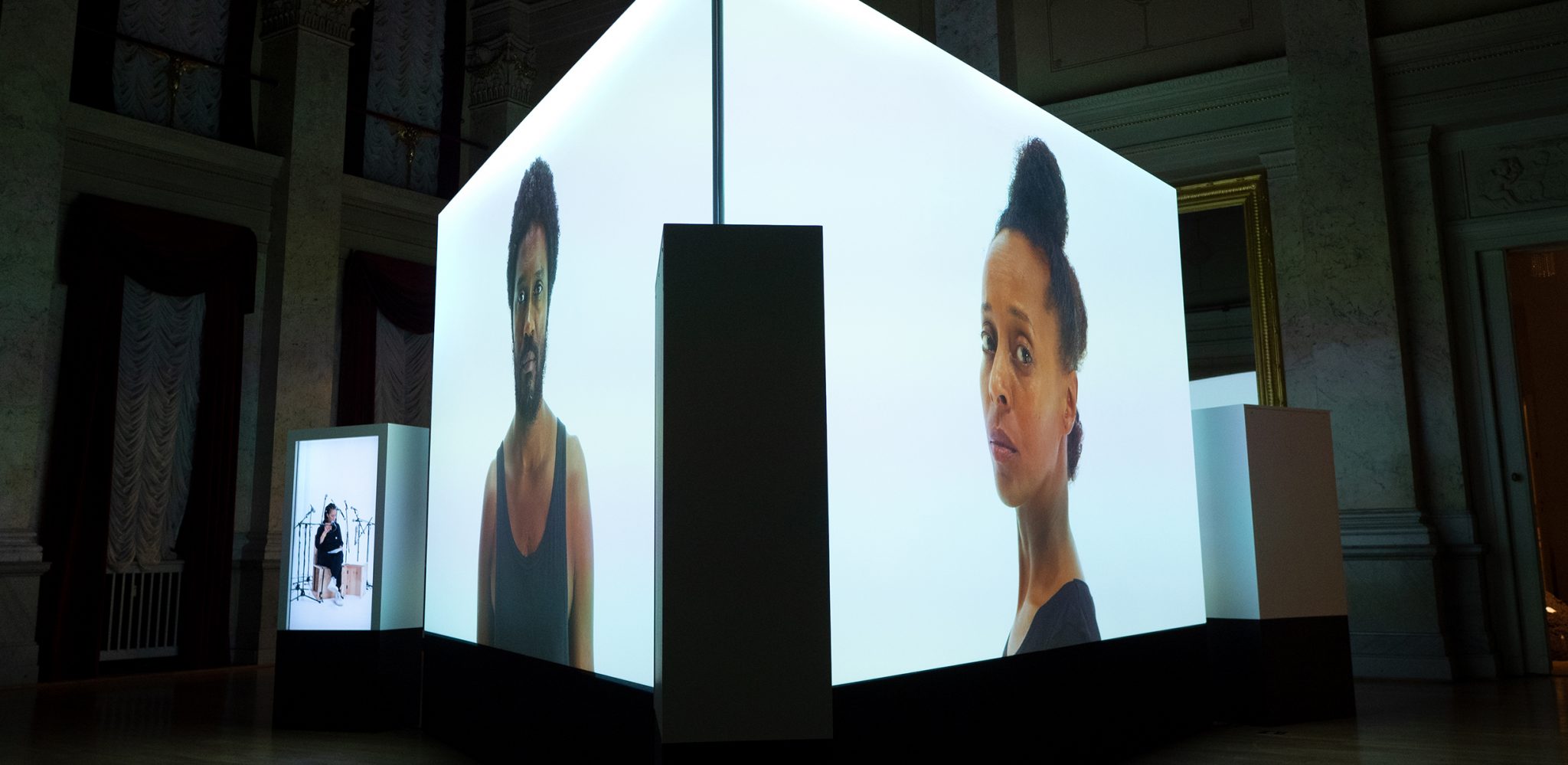

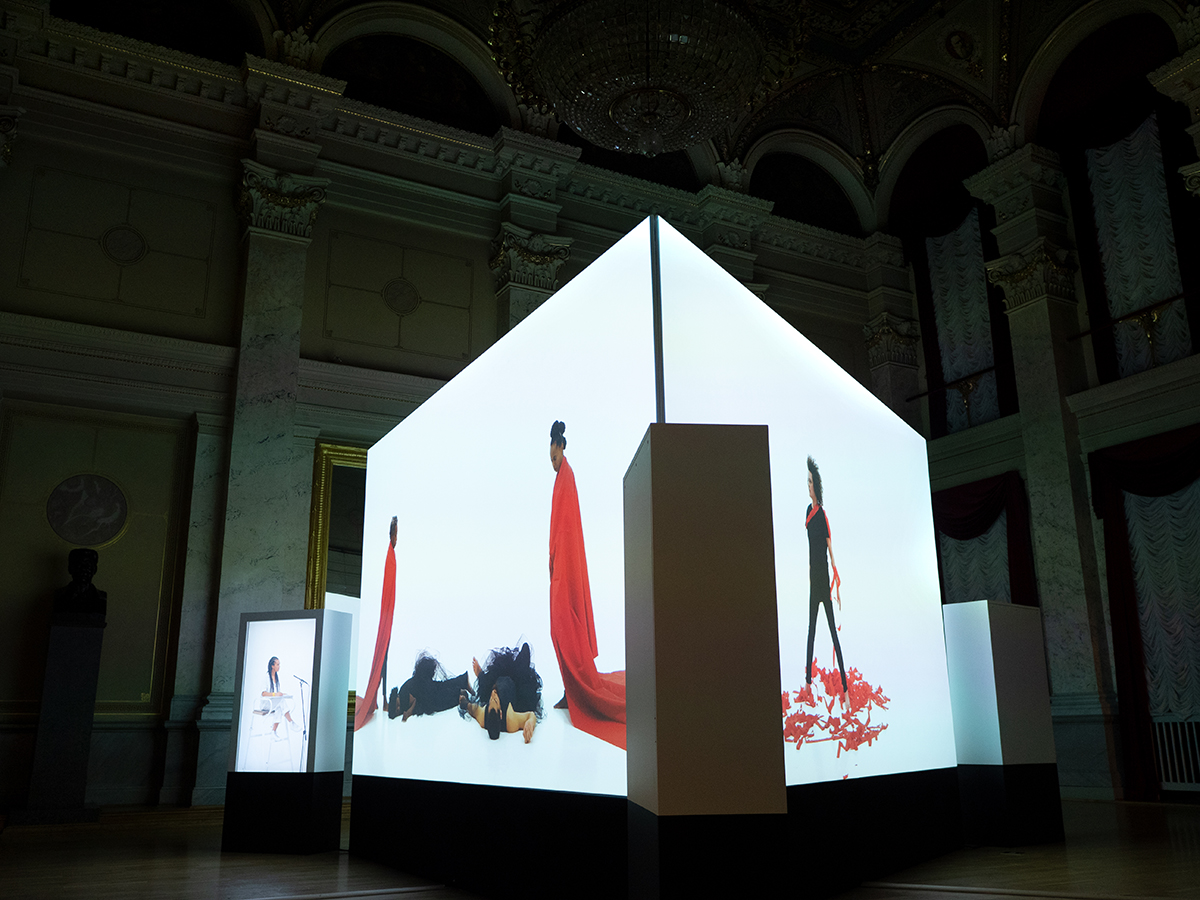

Ideas explored in Plantation Memories appear in Kilomba’s artistic output. Her first exhibition, at the Bienal de São Paulo (2016), presented The Desire Project (2015–16) and the first iteration of the video and performance installation Illusions (later to become Illusions Vol. I, Narcissus and Echo, 2017). Illusions combines a chaptered video of the Greek mythological figures performed by a Black cast, alongside a live performance by Kilomba, whose storytelling methods reframe the audience’s understanding of Greek classics. Following this, Kilomba produced two more volumes – Oedipus and Antigone – forming a trilogy now known as A World of Illusions (2019) and from which a series of prints, titled Heroines, Birds and Monsters (2020) and depicting specific scenes and characters, have been made.

As Kilomba begins work on two new projects – The Boat, her first largescale installation, for which she is currently securing a venue, and an opera (also a first) that is being produced in collaboration with South African composer Neo Muyanga (who worked on the musical score for each volume of A World of Illusions) – ArtReview talks to the artist who refuses easy categorisation.

ArtReview In academia, there is the research methodology of participant observation, where the researcher is not a distant observer, but is physically and psychologically invested in their subject. This seems to be an idea that developed from Plantation Memories – ‘I am the describer of my own history’, you write at the beginning of this book – into your performance lectures and A World of Illusions.

Grada Kilomba This idea that the public participates, or feels involved, or decides how to engage with the work is an element I’m very interested in exploring. That’s why I like to work with storytelling – because it’s very active, and storytelling can come in the form of video installations but also in these largescale installations: you tell a story and people involve themselves – even physically in the case of my new work, The Boat. It creates a physical, almost biological, attachment between the audience and the work. They are part of the storytelling process. For instance, when I made A World of Illusions, it was a gamble to assume that the audience would stay [in front of the video projection] for nearly one hour to hear the story from the beginning to end. This kind of involvement is something I find very important when creating a work.

AR That has a lot to do with the tradition of story-telling – especially in the spoken form – the power to hold an audience in place, both in the bodily and imaginary sense. How do you keep an audience? And how do you reconcile the videowork with your spoken performance?

GK My role as a storyteller is based on the idea of a griot, a figure from West and Central Africa. The griot was a storyteller who was also a kind of living archive, who would tell stories that had been forgotten, or whose meanings had been forgotten. They also have a critical voice: they can tell a story in the form of a song accompanied by music, and then suddenly change tone and reveal another meaning of the story. This is what I wanted to do. To have this critical voice that could travel from one place to another, from one village to another, from one people to another, to remind them of something that was forgotten. To take narratives that we take for granted and to show that it might be more complex than we thought. So this role of the griot is also to show what is hidden behind each story.

For example, the story of Narcissus [who appears in the artist’s video installation Illusions Vol. I] is one we think we know, but actually if I place that story of Narcissus and Echo in the contemporary moment, I read it as a story about the politics of misrepresentation and invisibility. Narcissus can be looked at from another perspective. The other Illusions videos behave in a similar way: Oedipus is a story about violence and Antigone is a story about resistance and justice.

Practically speaking, I needed almost one year to create each of the three volumes in A World of Illusions. There was a long research process into the Greek mythologies of Narcissus and Echo, Oedipus and Antigone, as well as psychoanalysis, gender and queer studies, postcolonial studies and decolonial studies. I also dedicated some time to go to the opera, to explore the staging and imagery related to these Greek stories. In the videos, the costumes and props are very simple and few, which helps to create a naked space where the body and voice are prominent. My studio is round, and so the white background of the videos creates a sense of timelessness and infinite space. I also think it plays a bit with this idea of focusing on the narrative of a black woman. That the audience would enter this installation space and not be distracted by anything else; that they would be connected with these bodies, these faces, this narrative and the words that are spoken. It’s really a choreography between writing and the moving image.

A World of Illusions, 2019 (installation view, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin)

AR With your new work, The Boat, will you invite the public to engage in a similar way?

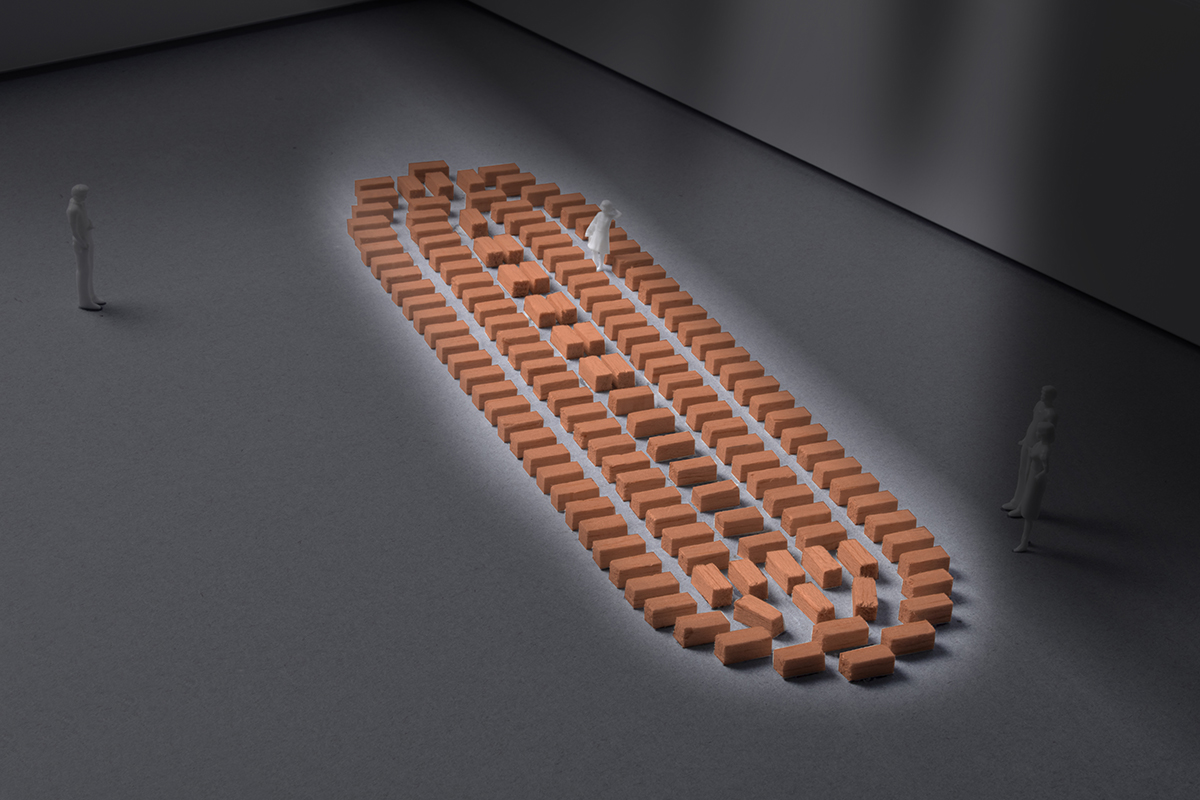

GK The Boat is a largescale installation that was created and shortlisted for a proposed memorial for people who were enslaved in Lisbon. It wasn’t selected, but I really felt the urge to make it happen and produce it, so I started working on it in the studio, experimenting with a three-dimensional form in clay, and collecting and writing poems. Now I’m adapting it for a gallery space. It’s composed of clay blocks that I will create with local communities. Each of these blocks represents a body that was lined up in the hull of these ships. We walk through European cities and see all these monuments and images that celebrate European expansion, and these boats are symbolic of that glory, greatness and adventure. The idea of the installation is to reveal the unconscious part of the boat – what is hidden in the hull – to reveal that story. It’s a very performative work: I will engrave poems on the clay blocks. People will be able to walk in between them, and read and show gratitude and respect to the ‘bodies’. I would like to make what The Boat represents visible in cities that were created and founded at the cost of slavery – where these narratives are not visible in public monuments or in gallery spaces.

And it’s not only about the past. The thing about The Boat is that the boat keeps returning. These ships are returning to Europe, crossing the Mediterranean from South to North, and they are also coming back from South America. It has become a triangular movement – people trying to migrate to Europe. I find these metaphors very strong, and they can be used as ways of telling stories anew – or revising the way we tell history. I think it can be very illuminating for the audience to be confronted by this sense of timelessness. We live with the past, present and future at the same time. For example, what Black Lives Matter is fighting for seems futuristic in a way – it’s something from the present, but we are claiming for an equality and humanity that does not yet exist; the present is not able to deal with such demands because they are seen as something for the future, and it is seen as something for the future because of what happened in the past. This timelessness is always there. The Boat is from the past, but is now in the present and reminds us of our future.

AR Can you tell me more about the poems?

GK They are very much linked with the research that I am doing. I’m looking back at the history of slavery and trying to reveal and connect stories and rituals that surround it – rituals of violence, of silencing, of genocide, but also rituals of healing. What’s at the centre of these poems is how to speak about humanity, to reveal how words and languages are not only poetic, but also very political, and can fix identities in one place. Each word really defines who is inside or outside, and who can represent the human condition.

AR You started developing The Boat at the end of last year, which seems particularly prescient given the events of this year, which have seen statues and memorials to figures who were complicit in colonialism and slavery being taken down…

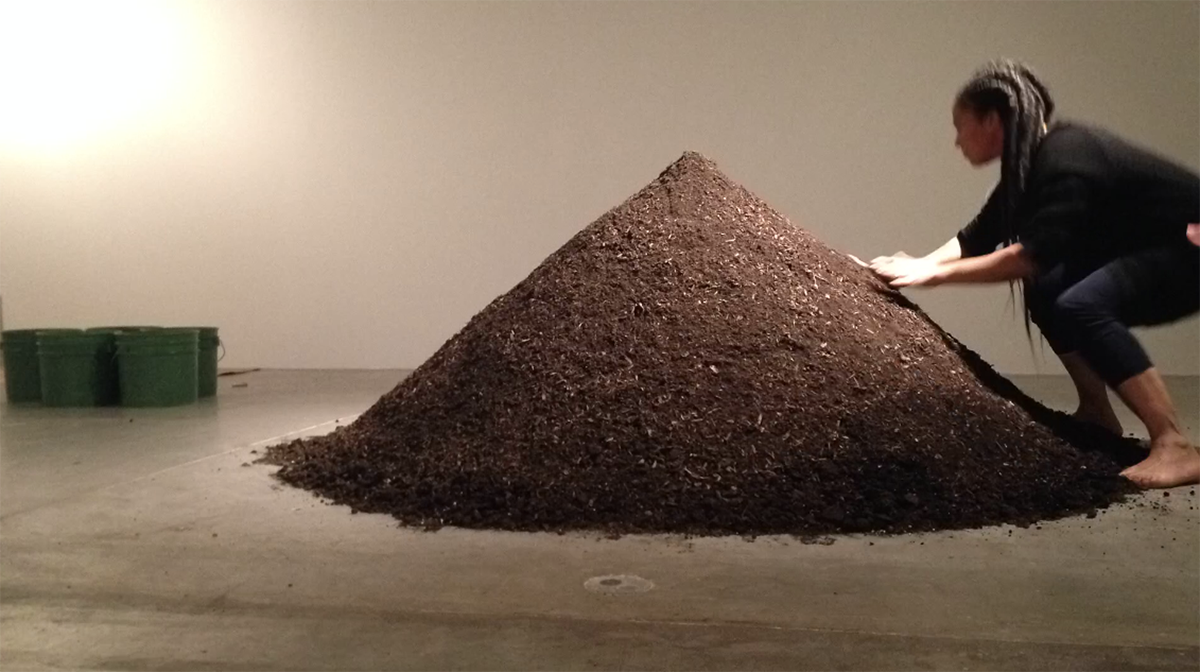

GK With The Boat I really wanted to occupy and interrupt the public sphere, or the gallery space, with another narrative that is usually hidden. It’s difficult for us to understand today’s racism, to understand that it’s a restaging of that time when Black bodies were first dehumanised. This history is a wound – a wound that was never treated, and always hurts, and sometimes gets infected. Sometimes it bleeds. It bleeds and gets infected because it never received the proper treatment. This idea of bodies that were not buried, or documented, or given a place for ritual ceremony or to be mourned – this isn’t inscribed in the monuments I walk past in the city. In Antigone, too, I worked with a pile of clothes that symbolically represented the dead body of her brother Polynices. King Creon would not allow her to bury her brother, and this reflects on the issue of who has human rights and who does not. Antigone challenges Creon, and chooses to follow the rule of the gods, which says that everybody needs to be and should be buried. Acknowledgment and respect in the act of burial is also present in Table of Goods [2017], a performance where I inter ingredients that were central to the slave trade – coffee, sugar and cacao – in soil.

AR That critical voice of the griot can also be traced back to the tone you use in Plantation Memories – there’s a sense of continuity in your method of telling histories, be it written or spoken. Twelve years ago, you wrote not just about everyday racisms, but also about the invisibility, the physical and psychological violence towards, and the silencing of Black people – and we are still seeing this play out today.

GK My work points at how narratives that place certain identities outside of humanity are created. How narratives are created to be universal, but do not take into account the reality of certain humans. So, when I look at these Greek tragedies, what is revealed to me? How do I look at the metaphors, associations and images, and how do I experience them? The story of Oedipus, in psychoanalytic studies, was seen as a story of desire. But I find that violence and the idea of genocide plays a stronger role in the story. It can explain so much about cyclical violence, about the repetition of violence and about the repetition of barbarity. Before he was even born, Oedipus was cursed to die because his father felt threatened by this child who was prophesised to kill him and marry his own mother. Oedipus cannot escape his own history.

This is also present in the figure of the Sphinx, who is sent to punish Thebes because something bad happened in that city in the past, which the people do not know about, or have forgotten. She asks a riddle, and those who cannot answer the riddle, she devours.

These metaphors show us that we cannot escape our history. We have to learn to tell our history properly, so that we know how to answer those questions. We have to know the answers, otherwise the Sphinx remains here, observing and devouring us. These Greek myths have all these beautiful metaphors that can be transported into the present time, with all these questions of race, gender and postcolonialism. The poetry of mythologies allows you to do something dramatic with bodies and choreography, but also to bring political and very critical discourses into it.

Heroines, Birds and Monsters, 2020, series of prints from World of Illusions, 2019, here featuring Sphinx Act II

AR You’re also working with Greek mythologies, which became foundational to white European culture, as opposed to choosing to look at mythologies from different cultures.

GK Other mythologies are not part of the canon of the European educational system. We grew up studying and learning about these mythologies and stories, which are absolutely beautiful, and I’m fascinated by them, because they speak of human tragedies and human conflicts that we all face, and the questions and decisions we all have to reflect upon. But these tragedies are delivered to us as universal stories, as stories of humanity. My perspective, my humanity, is not included in this universality. This is what I wanted to dismantle: how these stories are given to us in a ‘neutral’ space, in these white cubes that are as neutral as these stories of humanity. The very fact that Illusions is performed in a white infinity is exactly a metaphor of that perceived neutrality. No space is neutral. There’s an ‘ideal’ of what humanity is, and then there are biographies and realities that are considered subhuman or which are placed outside of humanity.

For instance, we have the Yoruba mythology that plays a very important role in religious activities, ceremonies and rituals – like the candomblé and capoeira, which I grew up with, and is celebrated in Brazil, Cuba and Angola – but that mythology was forbidden by the Portuguese in Brazil for a long time, and that lasted beyond their colonial rule until the 1920s.

We grew up with a politics of forgetting and of forbidden stories. It wasn’t just the Yoruba mythology, but many other rituals and practices were forbidden. And this relates back to The Boat too, as the transporter of these ideas. People were imprisoned if they were caught practising their own rituals and ceremonies. That’s why I also try to connect the storytelling in A World of Illusions to the ritual of arriving and sitting – and I find it fascinating that an audience would sit there for almost one hour. They look at these actors and listen to the music and the storyteller. They stay. This is the ritual of decolonisation for me.

AR That your work is hybrid in nature also suggests a form of resistance – to categorisation, for example.

GK This is also the basis of decolonisation – it’s exactly about going beyond each discipline to create new languages that are not loyal or obedient to one discipline or another. For example, if I am to tell my story, I cannot tell it with the language of disciplines that have colonised me: the language of the patriarchy and of the colonisers. We have to invent new languages. These hybridities, this confusion and fascination with not being able to place the work in one field or another, is necessary. Decolonisation is when you cannot read things as you used to, when the language has become unfamiliar because new people are telling new stories. There is now a generation of people who are really searching for it. With The Boat, I hope people will come, enter the work and read, listen and look. It’s a minimal work, but this is how I try to create intensity. When I almost feel afraid of showing a work, of being fragile – that’s when I know the work is ready to be shown.

AR Why is it important to make yourself vulnerable?

GK Vulnerability carries a sense of honesty. It’s the point where I feel there is nothing else I want to say now – that this is exactly what I want to say. Honesty makes it possible to connect with the audience. It can help the audience – who come from different generations, backgrounds and communities – to identify with the story you are telling independently of their own biography, because they are in a space where they can acknowledge their own fragility. And that’s the power of performance, the arts, of storytelling and dance.

AR This ties in to the idea of listening and silencing – and the way you create a space where people want to listen to you and will sit for an hour because they want to hear what you have to say.

GK I think the works create a space where people can actively decide to listen to those who are speaking. It’s fascinating because sometimes in the audience, people are sitting in front of seven black actors for the first time, and sitting for an hour listening to a story that they thought was familiar to them, only to find that other elements have been added, or another perspective they didn’t think about.

I think this is the moment where ‘universality’ and ‘humanity’ are questioned. I put Black actors into Greek mythologies because we are talking about human tragedies. All actors can perform these tragedies. In Antigone I worked with all women actors, apart from two men in one of the scenes, to play with the traditionally gendered roles: the women played King Creon, Haemon and the messenger. And still the audience sat and watched, because the story goes beyond these categories. That’s how I understood what the ‘politics of invisibility’ was – to turn yourself invisible in the sense that you can embody every story, occupy every space and go beyond what is expected of you…

All images courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, London