Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 in Sweden and died there in 1944. She painted abstract paintings under guidance from spiritual beings. She has recently been claimed as the true founder of abstract art.

ARTREVIEW

From obscurity you have suddenly become a guiding light. What do you think the spiritual is ‘ for’ now, in art, since it’s no longer a spiritual age?

HIlma Af KlInt

Well, you’ve said it right there. It’s something that’s different to the age and therefore attractive because of exoticism. But it has to be packaged. The spiritual content of my paintings has to be isolated from anything else the paintings might be about, or any other way of reading them. Otherwise the attractive message becomes too complicated and falls back into unattractiveness. In particular, since it’s art we’re talking about, there is a danger of art’s unapproachable character being too much in the picture: its elitism; the necessity, in order to understand art, to actually have made yourself familiar with it, with its history, its ideas and its internal dynamics. All that is less easily packageable than the notion of the spiritual; the notion of a woman artist in touch with spirit beings; plus in touch with a group of other like- minded women, with a brand identity: ‘the Five’; and the notion of all of us in the nineteenth century receiving communications from the Beyond, and me putting that spiritual material into paintings that are now available, having, as you say, languished in the darkness, for exhibition round the world. And since they were created so long ago, those very same paintings will now, it is claimed, change the whole idea of the history of abstract art. It will no longer be male genius-oriented. A woman will be there at the head instead.

Wow, that sounds great, what’s the problem?

H A K I think it undersells or ignores art’s concrete meaning. You know, if you’re a painter you spend a lot of time getting things right, getting forms to be efficient so that whatever you’re hoping to get across can have a chance of being coherent, of actually communicating to someone. You’re basically narrowing down to a very visual priority. But in the way ‘the spiritual’ is understood in the age of consumerism, it is basically anathema to the ‘right’ or the ‘efficient’ in art, and it fits very well with most people’s – including professional art people’s – completely unvisual idea of art at this moment.

Hmm…

H A K Yes. But on the other hand the spiritual is just a concept, and the paradox is that the actual art – the paintings and so forth – that comes under the conceptual heading of ‘spiritual’ need not be unvisual; that is, it need not be the thing its visually ignorant admirers want it to be: a relief from seriousness. It could actually be serious. This happens a lot in fact. Paul Klee is admired for idiotic unvisual reasons, and yet he is a supreme visual organiser. Even with Francis Bacon – a great trawler- through and putter-together of disparate art-historical surfaces – you can ignore the screams (which are for people who aren’t interested in art) and instead appreciate Bacon’s designer flair: the swift, sharp way he divides the whole area, its unexpectedness and the playful contrasts of mess and order. Peter Doig: fantasy imagery, and yet beautiful visual arrangements sometimes. The trouble is, no one has yet taken the trouble to see my paintings in this ‘seeing-through’ way. I assume the reason is that even if a critical observer were capable of it, they know it would be career suicide. You have to drink the new Kool Aid. You can’t combine it with the old Kool Aid of Clement Greenberg. But if you ask me, and so far no one has – after all, you still have Ouija boards don’t you? – if you ask me, Greenberg’s willingness to look at form in art would be helpful. He was perfectly open to things he is so often erroneously assumed to be closed about, but he gave these matters their place: he thought when he was looking at the visual it was the visual, not the poetic. His clarity is possible because he is confident and clear about categories. I maintain this would helpful right now.

What do you mean?

H A K I mean profound seriousness in the realm of the visual is different to momentary or passing solemnity about spirituality. Plus, I should say – and this isn’t particularly a Greenbergian idea, but I’m sure he would agree – if you’re an artist what you do is always a matter of making and knowing, not just one or the other. It’s not so much that if you don’t know much then your painted (or sculpted or whatever) work will always be crude. It’s more that the kind of things you know, the directions of your knowledge and enquiry, will always be there in what you make. You make what you are; you are what you know.

That’s a good slogan!

H A K Yes. So if your enquiry is profoundly unvisual that will be the nature, too, of what you produce. And it simply can’t be said that the origins of abstraction lie in unvisual experience. The big three founders of abstraction – Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky – were drawn to Theosophy, to the writings of P.D. Ouspensky and Madame Blavatsky, as its says in all the press releases promoting my paintings, written of course for infantile minds. But what you will never find in these press releases is the fact that these artists were also rigorous analysers of the forms of art throughout history. And each of their formal experiments – the look of art they each came up with, each so different, each a pure abstraction, never seen before – is clearly produced by this kind of enquiry and not by the other kind.

Uh?

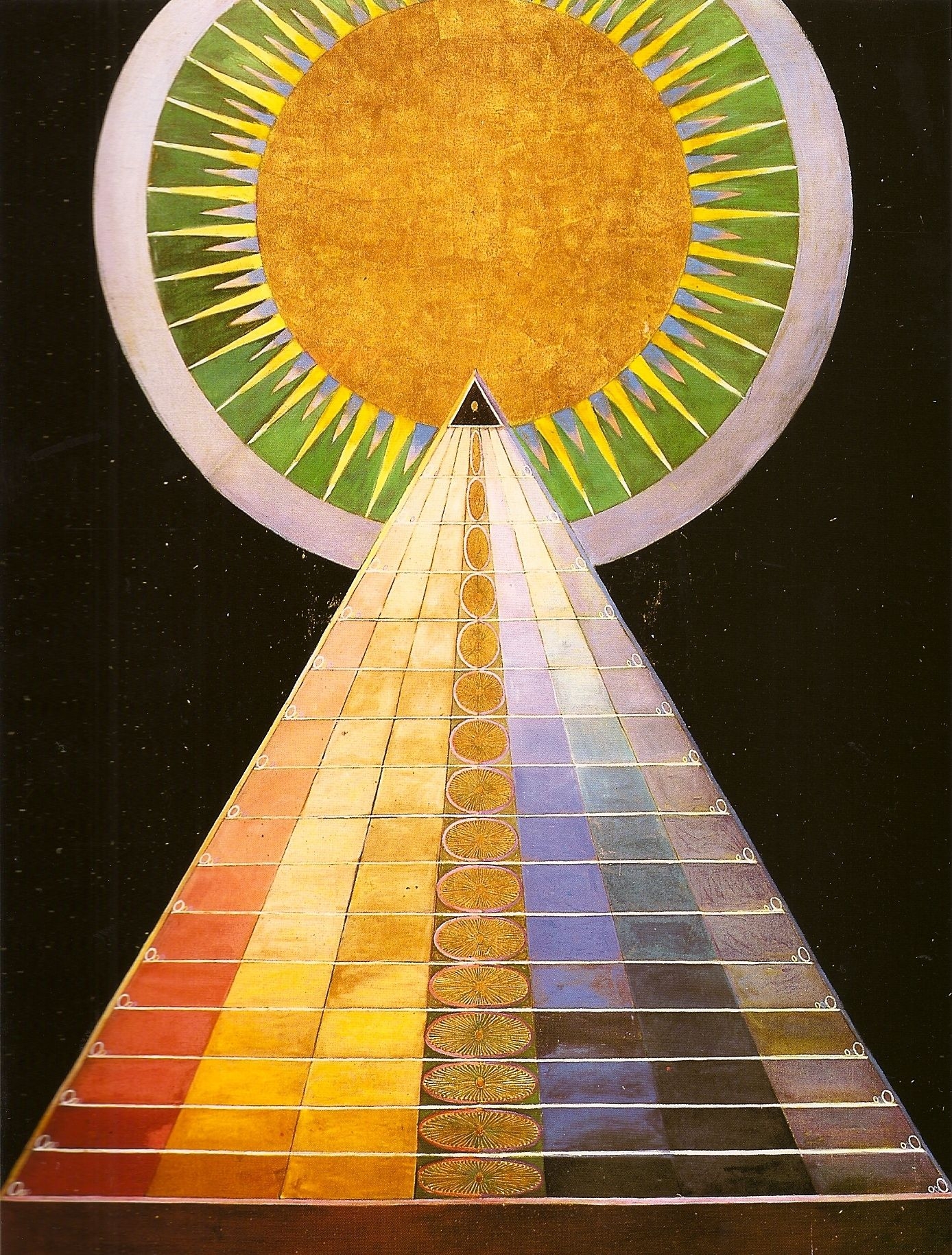

H A K They are produced by art, not by spirituality. If your understanding of my work is dictated by press-release knowledge, then you will know that I am a spiritual artist, that I received instruction from spirit beings and that they even had names – one of them was called Gregor. Well, as far as it goes, this in fact true. Consider the scene, in the 1880s. I’ve been out of the Swedish academy for some years; I’m painting portraits and landscapes to make a living; at the same time I’m communing with spirits. Gregor tells me something important; he tells all of us in the Five about a certain branch of knowledge – and here I’m quoting his discorporated voice directly: “Not of the senses, not of the intellect, not of the heart but is the property that exclusively belongs to the deepest aspect of your being… the knowledge of your spirit.” But he doesn’t tell us to make it geometric, or make it a cone or a pyramid within a rectangle surmounted by a semi-circle. He doesn’t say to imaginatively balance harmonies and contrasts of muted colour. He doesn’t say to give the balance a certain tough rigour. He doesn’t say to vary a geometric form with a freer organic one. And the same goes for Mondrian. Theosophical enquiry tells him this world is unreal, and the real one is yet to come. But it doesn’t tell him to paint the real one in primaries. When Malevich reads Ouspensky, he doesn’t find in there the information to paint three sides of a square parallel to the edges of his canvas while allowing one to slant a bit. Where does this other non-spiritual information come from, the information about appearance, visual order, the rightness and efficiency of visual proposals, their surprise value, their visual energy? It doesn’t come from Gregor, or Helena Blavatsky, but from relevant enquiry, from other things that are also visual. That is, from the history of forms in art, from formal enquiry, from immersion in the look of art as it has been up to your own moment. The spiritual is as real as you want it to be, just as the ‘formal’ has meaning for formalists, and capital for capitalists – well, that would be more for Marxists, but you see what I mean.

You’re awfully garrulous! You love a chat. And you don’t seem to say typical spiritual things, quotable in press releases, mimsy riddles that the bored on Facebook would be happy to post to each other and feel something significant has happened in their lives. Are you sure it’s a good idea to be so forthcoming? It’s delightful, but is it helpful for your mystery woman profile?

H A K Well, I’m looking at what people in a consumer age want from a fiction such as ‘the spiritual’ when they’re thinking about art, and it seems to me they want relief from difficulty. Fitting with the consumerist imperative, they want to be plugged into something they already know, while enjoying an illusion of novelty. They want to be radically changed but only, of course, if it’s a passing thing; they really want to stay as they are. Consumerism offers rapid self-makeovers, so rapid and shallow that of course nothing actually changes, you’re just in this state of constant unsatisfactory stimulation.

What does the art audience already know?

H A K It knows art is a vision that pops into an artist’s head and the artist, who is a special person, different from all others, a chosen one, then pops the vision right back out onto a canvas.

Surely the experts know better?

H A K A state of ignorance about art’s actual nature is now shared by a relatively mass audience, newly signed up to art appreciation, and an inner elite whose job is to process art for everyone else: my stuff, which is as complex and multi-dimensional as I have already suggested, is the latest product up for processing. Its complexity has to be flattened in order for the main consuming message to be effective.

You mean the attractive narrative of creative female alterity, a visual version of Emily Dickinson, a female force, frightening and delicious, irrational, uncontrollable, but at the same time a bit reduced by being neatly stereotyped?

H A K Indeed. You’ve hit the nail on the head. Emily Dickinson for the distracted. If you are knowledgeable she is endlessly rich. Her poetry is capable of endless re-reading. My paintings are being fitted into a Dickinson shaped container, right now, but with none of the sophistication that exists in Dickinson-related literary studies. That is, they’re being packaged for the unknowledgeable, so they are being distorted. You’re getting fairy tales alone, narrative alone in a context that is inescapably visual. Narrative has its place in art appreciation, of course, I’m not complaining about it as such. The intertwining narratives of the artist’s biography, of art’s purpose generally in society at this moment, the narrative of the big pioneers of spiritual abstraction a century ago, of a female outsider coming in and claiming a prior achievement – getting to abstraction first. All this. But when narrative is the only focus of the art experience, the experience of painting – this discipline with its tangible realities, its materiality, its forms and colours – then there is a lack of understanding of what the experience is really about, and if you don’t understand that then you’re not really having the experience, you’re going through the motions only.

This article was first published in the May 2013 issue.