Hindu tradition and female experience are in tense relation, in drawings painstakingly made over months and years

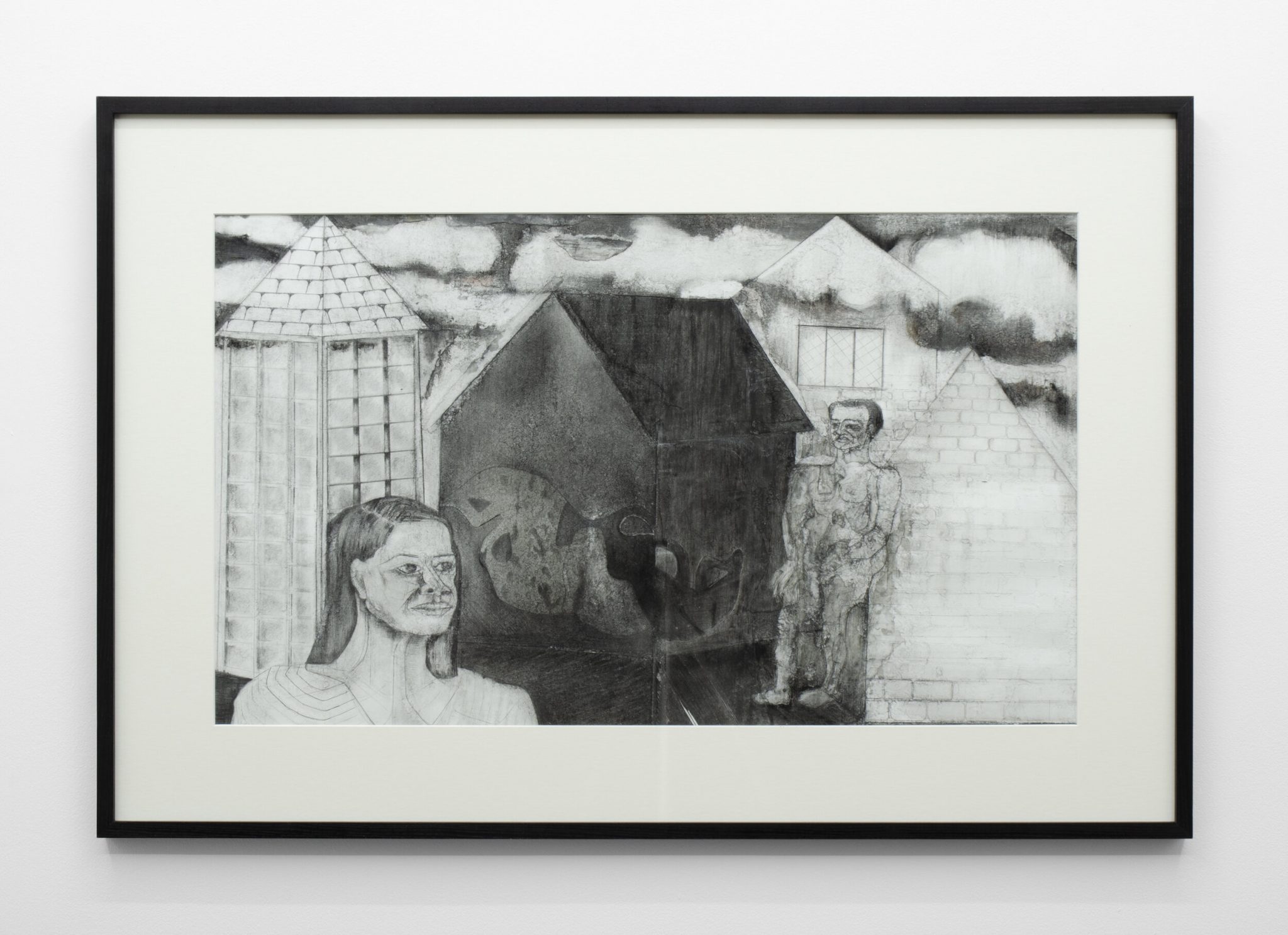

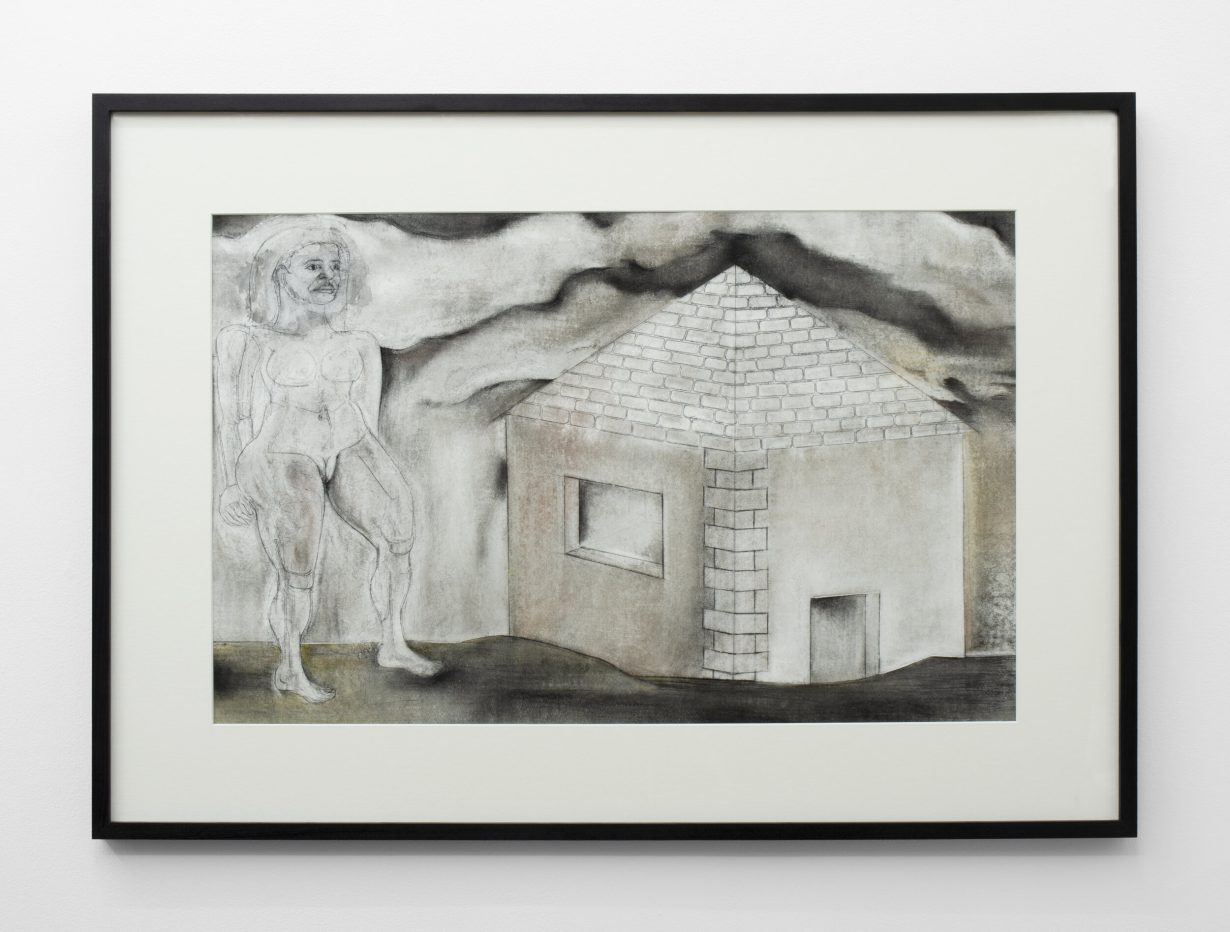

Gurminder Sikand was born in the Punjab in 1960 and has lived in the UK since she was ten. The impact of her dual heritage is evident in the five drawings at TG and weaves into Sikand’s figurative work an interest in the strength of women –such as those involved with the Indian environmental protest Chipko movement – and a fascination with the female body, recently regarding those women who bodybuild. The artist told me about a Hindu tradition that considers some women cursed if they are born at the wrong time of the year; some beleive they will become an early widow if they do not first marry and cut down a tree to break the spell. Approaching a work such as A Dance (all works 2018–21) with this in mind raises points of further interest. Is the tree in the drawing part of this ritual? Is the woman on the left ensnared in a cursed marriage; or does the constricting structure around her imply a vertical coffin, veiling her in a life akin to death? Quiet or suppressed violence permeates Sikand’s compositions, present in her acts of erasure, in the subject matter and the distressed surface of the paper. It is to the artist’s credit that this simmers rather than dominates, allowing Sikand’s work to encourage a rich complexity of possible narratives. Meaning is just as much embedded in the surface of the paper as it is in the iconography or narrative of what is depicted. Equivocal in nature, the drawings are at once precise and open.

My thoughts after leaving Sikand’s exhibition dwell on to how the time of making and viewing can be folded into works of art. A focus on slowing down can be aligned to the exquisite drawings on show. Three years is a long time to make a drawing and the history of making of these drawings is evident. Sikand’s process involves an obsessive attention to rendering things precisely as she wants them, resulting in an accumulation of pencil marks, charcoal and Conté crayon, as the artist attempts to get the form, line and detail or her subjects just so. Her process also involves much partial erasure of these marks using rubbers, sandpaper and wire wool, leaving a residue of what was once there. The drawings are like palimpsests – manuscripts that have been erased for reuse but still bear visible traces of earlier marks. In Woman and Cell we find multiple positions of the feet and hands, alongside minute changes to the slates on a roof.

As we explore the surface of Sikand’s drawings, a strange elongating of time occurs. Her work holds, for me, what artist Vija Celmins has termed ‘compacted time’, in which time spent making a work appears invested in its physicality, which, as Celmins says “slows the image down”. The Slow Movement is not just about taking a long time but, as author of In Praise of Slow (2005) Carl Honoré writes, in ‘savoring the hours and minutes rather than just counting them’ the quality of experience offers an alternative to our capitalist-driven culture of speed. These drawings invite the viewer to look hard and spend time with them. As viewers, we can sense the care and precision that Sikand has put into her work, and feel a mutual benefit of being able to slow down in and experience the benefit of the heightened attention that an artist brings to a work that reciprocally allows us to notice things better.

Gurminder Sikand: The Weaver of Songs is at TG, Nottingham, until 28 August

This article is part of Remark, a new platform for art writing in the East Midlands by ArtReview in collaboration with BACKLIT. Read more here and sign up for the Remark newsletter here