Evidence of Theatre at Greene Naftali, New York wryly critiques how humans have stewarded the planet

An LED screen fills the upper floor of Helen Marten’s two-floor solo exhibition. The CGI video, Writing A Play (dark blue orchard) (all works 2023), features wintry landscapes and derelict interiors in which there are no people, only half-eaten meals, deserted laundry lines, ‘I Voted’ stickers and plastic waste visited by the occasional animal. Actor Gwendoline Christie narrates a fragmented tale about absent characters, including “a man with a pebble in his shoe”, someone vomiting fluid, lovers sleeping under a feather and a child learning new vocabulary. Christie’s tale, which rumbles from speakers around the screen, contains a refrain borrowed from cultural theorist Roger Caillois: “Butterfly, plus elephant, plus cat, plus dead man, plus sailor, plus nun equals deer”. Coupled with the solemn landscape, the allusions to death, water and spirituality call to mind another text, T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land, in which winter blankets the barren and corrupted earth in ‘forgetful snow, feeding / A little life with dried tubers’.

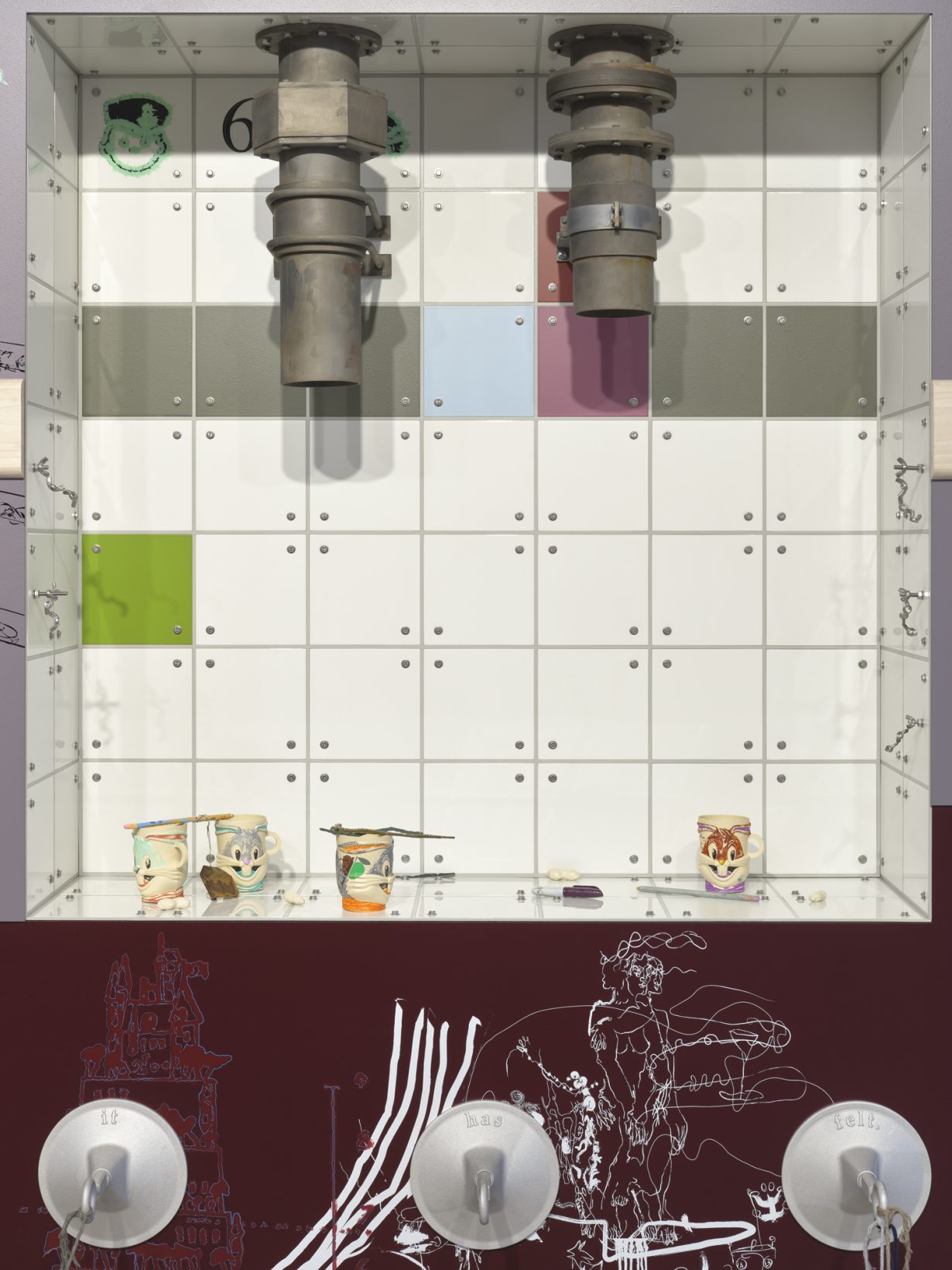

Marten is known for invoking twentieth-century thinkers, and this exhibition, spanning both floors of Greene Naftali’s West Chelsea site, is no exception. The paintings, dioramas and sculptures in the ground floor gallery contend with Sigmund Freud’s legacy. Tissue boxes and doll-size chaise longues appear, for instance, in the diorama Evidence of Theatre (they wept), mounted on colour-blocked aluminium panels under 1960s Kellogg’s advertisements featuring Freud’s bespectacled face. ‘He says you can “test reality”’, the ad reads. ‘Bite down vigorously on our Corn Flakes. They scrunch back just enough to give you a pretty fair clue that the world around you has substance.’ (The meandering narration in Writing A Play seems, in light of this, to reference Freud’s talking cure.)

The downstairs works that have no psychoanalytic innuendo, particularly those consisting of household kitsch and detritus, risk feeling secondary to Writing A Play, like souvenirs extracted from its rich CGI world. The video yields the show’s most pointed social commentary, and one of its most poignant images: a car totalled and rusting in the woods, with plywood, rocks and paper flyers festooning its hood. Tied to the car are two balloons: one is painted to resemble a clown’s face, the other, a blue and green Earth, which explodes partway through the video. Downstairs, the sculpture Modern Sluice, whose components include an exhaust pipe, a paper boat and a toy ice truck, alludes likewise to stulted mobility but, lacking the CGI assemblage’s tragicomic juxtapositions, appears smooth and withdrawn.

While Marten’s three-dimensional works are not overtly political, Writing A Play wryly critiques how humans have stewarded the planet. “Landscape is always a great eyeful, quiet as a mouse,” Christie says at one point. “We thought it would be nice to mix some chemicals to enlarge the space.” The cinematic eye hovers over an empty nursery, a drained swimming pool, a dead deer in the snow, a spontaneously combusting frog and, most disturbingly, tents and tin-wall huts evoking notions of displacement, migration and material decline. Just as Eliot wrote about the barrenness and corruption of his generation, Marten’s snowy, posthuman ‘wasteland’ is an elegy for this troubled century.

Evidence of Theatre at Greene Naftali, New York, through 4 November