From John Giorno’s Dial-A-Poem to Angharad Williams, what happens when artists adopt the telephone as a medium?

When he was twenty, Alexander Graham Bell, the elocutionist’s son who would later invent the telephone, trained his family’s Skye terrier to pronounce the sounds ‘oo ah oo ga ma’. Credulous witnesses interpreted this as evidence that the dog could ‘talk’. During our respective quarantines, I have been calling my ninety-year-old grandmother’s landline daily. She doesn’t have a mobile or a computer, so it’s the only way to reach her. I often catch myself, at the start of our conversations, echoing Graham Bell’s miraculous mutt: “How are you, Grandma?”

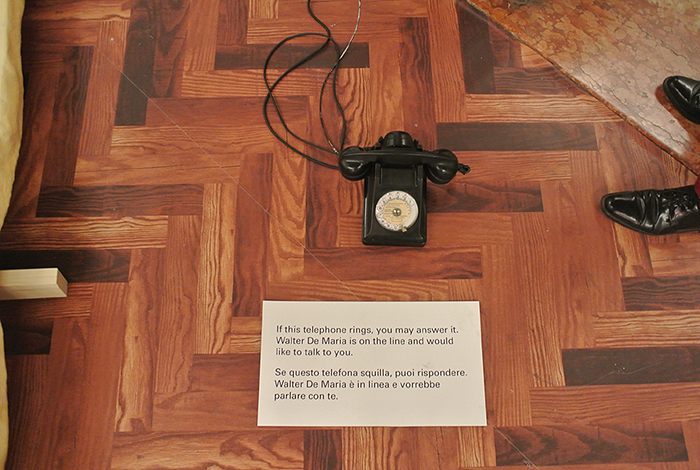

Phones offer access to voices and people we wouldn’t hear from otherwise. In 1968 the artist and poet John Giorno set up a phonebank in New York, called Dial-a-Poem. People could call a number and hear randomised recordings of poetry readings, political speeches, Buddhist mantras, rants and songs. By distributing live poetry beyond the confines of the avant-garde recital – Giorno liked to claim that Dial-a-Poem helped inspire the internet – the project offered the frisson of intimate, immediate access to a cultural figure who one might ordinarily never encounter in person, let alone have a phone call with. A caller might find themselves with Allen Ginsberg in their ear, proclaiming about “a telephone link to all the hearts of the world beating at once”.

‘Telephone’ is a portmanteau of the Greek for ‘far’ and ‘voice’. However thrilling it would be to have a direct line to a famous poet, it jars to feel so near to an absent person about whom you care. (Kraftwerk put the paradox succinctly: “You’re so close but far away / I call you up all night and day”.) The very first words transmitted via a proto-telephone, in 1876, in Graham Bell’s Boston laboratory, sought to close the distance between speaker and listener. ‘Mr Watson, come here – I want to see you,’ said Graham Bell into the mouthpiece, summoning his assistant from next-door. When I speak with my grandmother, her soothing, raspy burr and her wicked, snickering laugh are so faithfully reproduced that I never ask for visual proof that it’s really her. That what reaches my ears in response is a facsimile of her voice – Graham Bell’s invention converted sound waves into electrical signals, which were sent down a telegram wire and converted back to sound at the other side – never registers in my experience of the call.

I sometimes wonder if I should exercise greater suspicion. As John Barron aka David Dennison aka Donald Trump knows better than many, phones can be a scam-artist’s signature instrument. You don’t need a slick suit and a beguiling smile, just chutzpah and a plausible accent. That such dishonesty is commonplace points to the trust we instinctively place in the voices we hear on the line, particularly those we know best. Describing how testosterone injections changed his voice during his gender transition, the philosopher and curator Paul B. Preciado observes that the phone, that ‘faithful emissary’, began to betray him. ‘The voice is the mistress of truth,’ he writes. Yet, when his mother fails to recognise his altered timbre on the phone, he wonders: ‘Am I really her child?’ The phone can be used to deceive; equally, it can reveal more than we intend.

For the phone phreaks of the 1960s and 70s, telephone networks offered opportunities for wayward engineers – a young Steve Jobs among them – to beat telecoms companies at their own game, while for postmodern theorists of later decades, the phone became an emblem of schizophrenic society. Yet neither of these histories has helped me understand why, despite the sudden and not entirely welcome ubiquity of Zoom video-conferences, the humble landline continues to feel so vital. Under quarantine, I’ve found that the qualities that used to give me a disproportionate sense of stage-fright – a variation on the panic that can attend public speaking – are now the source of its most urgent appeal. Given the multitude of pop songs about answer machines, lost numbers, hotline blings and so on, it’s perhaps surprising how few artists have followed Giorno’s example and adopted phones as a medium. When they do, it can be memorable.

Back in 2013, the artist Angharad Williams performed her work Breezer in a South London gallery. She asked a member of the audience for their phone number – cue nervous side-eyes and awkward titters – then promptly left the gallery and called the mobile number of one of the audience members from the park outside. Having been left nonplussed by her departure at first, the group of us, maybe 15 strong, huddled around the device. As she walked around the park, Williams read a text about a teenage girl taking her first sip of Bacardi Breezer. Filtered by the iPhone’s tinny speaker, overlaid with buffeting sounds of wind and playing children, Williams’s voice sounded fragile and whispered, like a late-night answerphone message. The phone’s sonic qualities, which emphasised the seductive sibilance of the artist’s delivery, felt doubly apt: a nostalgic evocation of the fumbling, desire-filled chats I used to have on brick phones when I was the same age as the girl in the piece. By requiring that the audience twist their necks and bend their ears towards it, the phone further subverted the expectation of spectacularism that attends so much performance art. The environment felt so close – so private – that I remember feeling mildly scandalised to be sharing the experience with other people. The phone, that technology of breathy answerphone messages, of whispered, late-night chats, of hearing the voices of loved ones and knowing they are safe, held the audience transfixed – until, abruptly, the artist hung up. The performance was all the more forceful for being so quiet: for drawing us into the paradoxical scope of a close but distant voice.

Patrick Langley is a writer and editor based in London. Listen to Patrick discuss the history of telephone art in ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object, Verb.