‘The Other Story’, the Hayward Gallery’s show of Afro-Asian

artists in post-war Britain (29 November 1989 – 4 February 1990), received a rough ride in the press. But in the January 1990 issue of Arts Review, Jane Bryce took issue with what she described as the “extraordinarily patronising tone of most of the reviewers”.

The Other Story, says Rasheed Araeen, curator of the exhibition, “is not a question of accepting or rejecting the white culture’s notion of quality in favour of some mythical black aesthetic, but of engaging and questioning the dominant art practice”. It is impossible to do this without confronting the aesthetic arbiters, the mainstream critics, whose attention is the measure of the significance of any artistic event.

Organisers of exhibitions of work by Afro-Asian artists know how difficult it is to interest the mainstream press in anything that can be labelled ‘black’ or ‘ethnic’. Exhibitions like the Whitechapel’s From two worlds: 16 young artists of non-European backgrounds in 1986, or Zamana’s Art of south-western Nigeria in 1988 were resolutely overlooked by all but specialist publications like this one. Araeen’s achievement in staging his exhibition ‘In the Citadel of Modernism’ (ironic title of the show’s first section), after eleven years of perseverance, is at least in part, that it could not be ignored.

The critics’ comments create the parameters within which the artist’s work will be viewed and assessed, and, cumulatively, contribute to situating it within contemporary art history. There are those, like the contributors to the catalogue, who have consistently demonstrated an informed appreciation of those Other voices counterpointing the establishment Story. They in turn are countered by the frontline of the establishment defence, which posits, in opposition to Araeen’s question: “Why is there no open or public debate about the absence of non-European artists from the history of modern art?”, “Why have Afro-Asian artists failed to achieve critical notice and establish a London market for their work? To that the answer is short – they are not good enough. They borrow all and contribute nothing.”

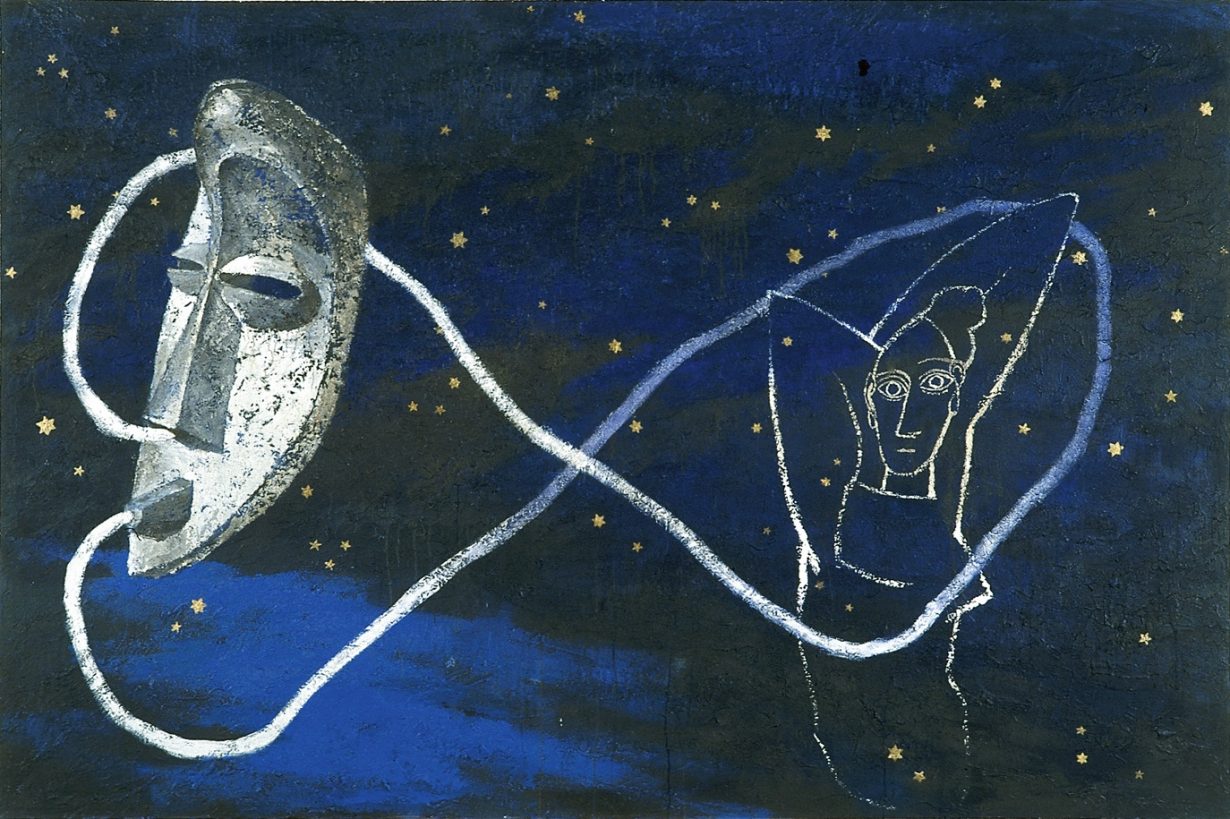

The notion of ‘originality’, central to criteria of modernist ‘excellence’, is, at best, extremely unstable. An untitled painting by the South African, Gavin Jantjes, explicitly points to the modernist borrowings of such artists as Ernst, Klee and Picasso. These unattributed borrowings are part of a tradition of appropriation which includes Aesop’s Fables (now seen as Greek); the influence of Islamic poetry in the medieval courtly love tradition, so strenuously denied by Christian commentators; Chaucer’s borrowings from Boccaccio who borrowed from the Arabian Nights; and Dante’s reading of rural Indian folktales, explored in this exhibition in a remarkable series of paintings from the Divine Comedy by Saleem Arif.

The polarisation of values fundamental to western culture and philosophy is radically questioned by The Other Story. The named vs. the unnamed, traditional vs. contemporary – such dichotomies are examined, both seriously and playfully, and ultimately synthesised in a way “that very exclusive hell called the English art scene” has no language for. Instead, “Avinash Chandra’s 1950’s concoctions of squiggled biomorphs and wriggling, abstracted body parts look dated, uninspired responses to Klee or Ernst” rather than being recognised as arising directly from Indian painting tradition.

The critical consensus on the work of these 24 artists from Africa, the Caribbean, India, Pakistan, Palestine, Japan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, China and England, from Ronald Moody, born in Jamaica in 1900, to Sonia Boyce, Keith Piper and Eddie Chambers, born in the UK in the 1960s, is “tame and derivative”, “not particularly convincing or enlightening… for the simple reason that much of the art displayed is not very good” The conclusion: “For the moment, the work of Afro-Asian artists in the west is no more than a curiosity, not yet worth even a footnote in any history of 20th century western art”.

What is at stake, in a nutshell, is the history of modern art, and the exclusivity and status of the works which form its mainstream. The Other Story, far from being a footnote, is more like jazz improvisation, a daring synthesis of the familiar and the strange, full of dazzling departures, humour, irony, abstraction and experimentation. It has no difficulty in paying homage to the ancestors, while being fully conscious of its part in contemporary artistic expression.

The excellent gallery talks by black artists giving their personal responses are a recommended alternative way into this exhibition. Jacques Rangasamy, talking about the significance of light in Indian sculpture, illuminated the work of sculptor Avtarjeet Dhanjal, which “unites the two first principles – black, dense stone, animated by light”, in the form of flickering candles inset in rock. This synthesis, which he traced through the work of several other artists, is opposed to the thesis and antithesis of western art historical discourse. “We have”, he said, “to talk of potential – the history of this exhibition begins now and is yet to be written”.

First published in Arts Review, January 1990