A new show at Storage, Bangkok takes a range of subaltern, diasporic and postcolonial perspectives on home and belonging

Dieneke Jansen’s relationship with housing is complicated, as her video essay This Housing Thing (2021) makes clear. Footage of family photo albums supplement a voiceover in which the New Zealand-based artist recounts living during her student days in a “major health hazard” of a flat, back when “seventy-one percent of households were in home ownership”. Her oral account, which is accompanied by an unspoken internal dialogue that appears as onscreen text, then cuts to Amsterdam, where she resided in a squat and became involved in “negotiating anti-capitalist ways of living”. These accounts of privation are juxtaposed with temporal shifts that raise the spectre of inherited privilege – we learn of an ancestor who, whilst working for the Dutch East India Company in the 1700s, owned land in Jakarta, for example, and that, after emigrating to New Zealand from Rotterdam, Jansen grew up in a series of “big privately owned houses” in Auckland.

These are intriguing, genealogical plot points. Yet Jansen’s history with property seems less important than the fact that she introspectively cross-examines it through this arresting video: she confronts her own hypocrisy (‘Did the squalor give me some sort of kudos?’), wrestles with guilt (‘I apologise for taking up a place in a squat that I need not have’), and points to the absurdity of land ownership in New Zealand (‘What is public on colonised land?’). This considered evaluation of her position as a non-Polynesian New Zealander forms a counterpoint for thinking more widely about this exhibition about home and belonging, which also includes commissioned moving image works by three other artists. All ‘sparked’ by Jansen’s film, and spanning the Asia-Pacific region, these foreground a range of subaltern, diasporic and postcolonial perspectives.

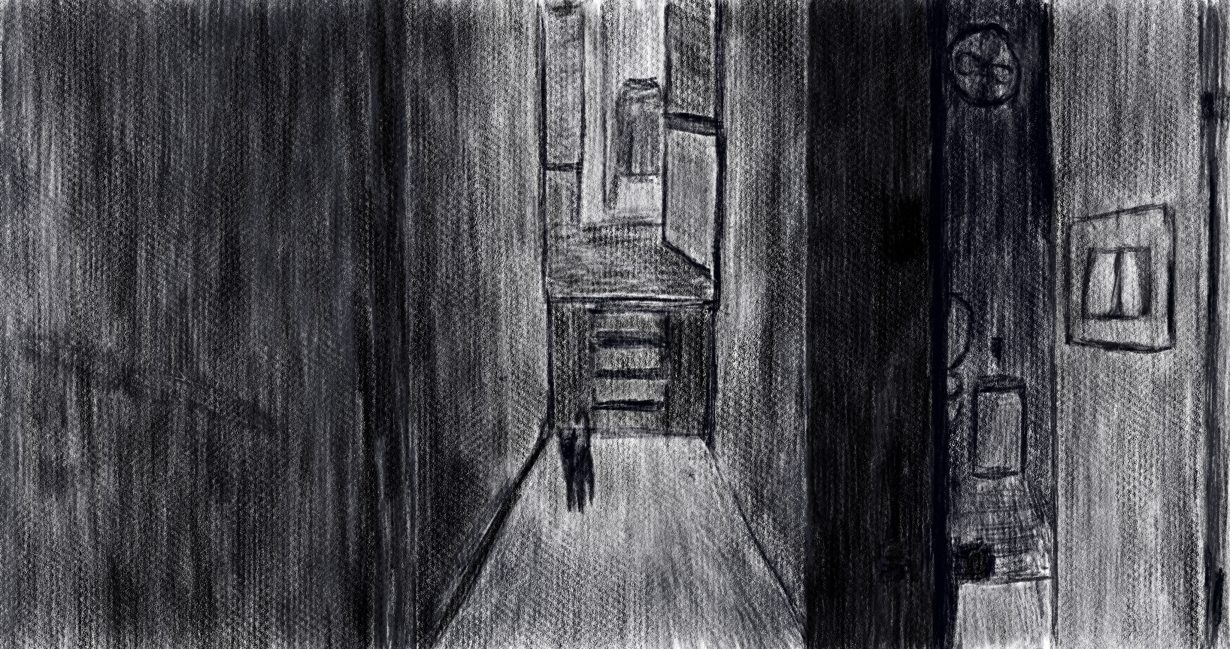

Most rooted within the local context of Bangkok is Ananta Thitanat’s pencil-drawn animation Siam (2024), in which her father recounts his decades spent working in one of the city’s last standalone cinemas. Prior to it burning down in 2010, the Siam was more than just a movie palace, he explains, as its corridors, auditoriums and projection rooms doubled up as free lodgings for the thrifty staff, most of them migrants hailing from the countryside. Crashing on folding beds set up in corners of the cinema allowed them to save on rent and travel costs; and the boss was happy with this arrangement, too, as the staff kept an eye out for thieves or petty criminals. “It’s like having someone at home looking after things. It became a home,” he says. Aside from her father’s testimony, the pathos of Thitanat’s understated work lies in her stark, expressive pencil drawings of the Siam’s interiors, which fade in and fade out of the animation – and the poignant realisation that this typology of Thai cinema, and the makeshift social housing and support network it offered employees, is now extinct.

The satirical tone of Ari Angkasa’s two-channel Quantum Leap (2024) offers a striking contrast. Deploying footage centered on Indonesia’s aviation industry, it includes clips related to the EU’s 2007 ban on flights from the country, due to lax safety standards. Angkasa pokes fun at this period of national humiliation by performing dual, often competing, versions of a kebaya-clad air hostess delivering an in-flight safety briefing – she is sometimes alert and professional, sometimes clumsy and distracted. These vignettes generate the exhibition’s most tenuous and cynical link to the theme of belonging: a sense that it can be shaped by, or in reaction to, civilising strains of neoimperialism, including airline safety inspectors.

Drawing us back to lived experiences in Aotearoa (New Zealand) is Kahurangiariki Smith’s Mā te Moana (2024), which takes what feels like the exhibition’s guiding impulse – a search for what Jansen calls “an at-homeness” – in a decidedly abstract and spiritual direction. Smith’s phone footage documenting the journey of Buntheun Oung, a Khmer tattooist she met at art school in Auckland, back to rural Cambodia, is bookended by animated Māori forms, and invocations of the ancestors of her Te Arawa tribe, who migrated in canoes to Aotearoa from their islands in the Pacific. “This is his return to his homeland. This is my return to the moana (ocean),” she says. As she invokes Māori seafaring folklore and wonders how mankind split the open seas, one senses a subtext of resistance to settler colonialism, but also that, in her worldview, home and belonging has more to do with the mobility and stewardship of intergenerational knowledge than it does the politics of housing, possession or dry land.

Homing Instinct at Storage, Bangkok, through 2 December

From the Winter 2024 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.