How the terrestrial mail system became a means of exploring rivers, stories and outer space

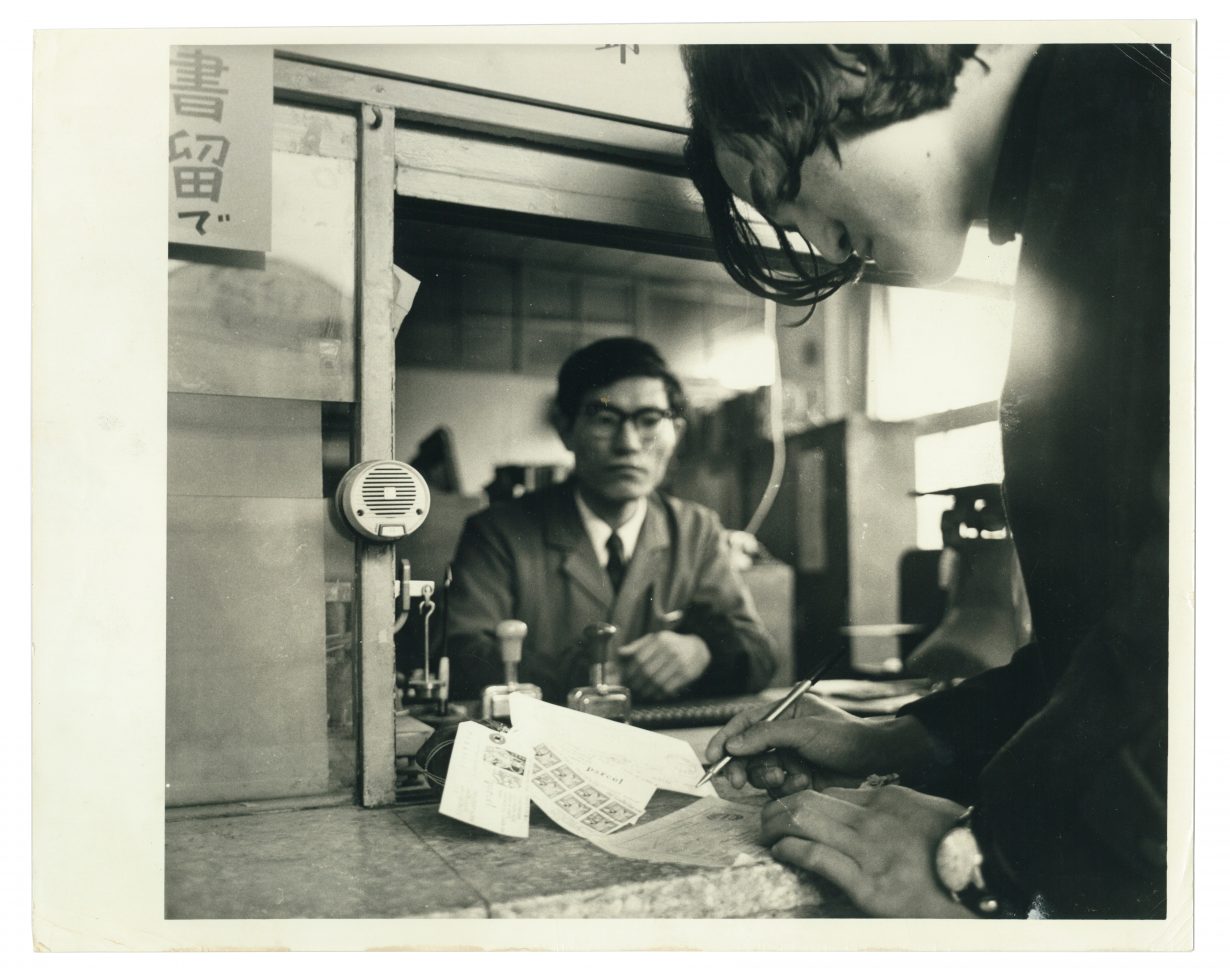

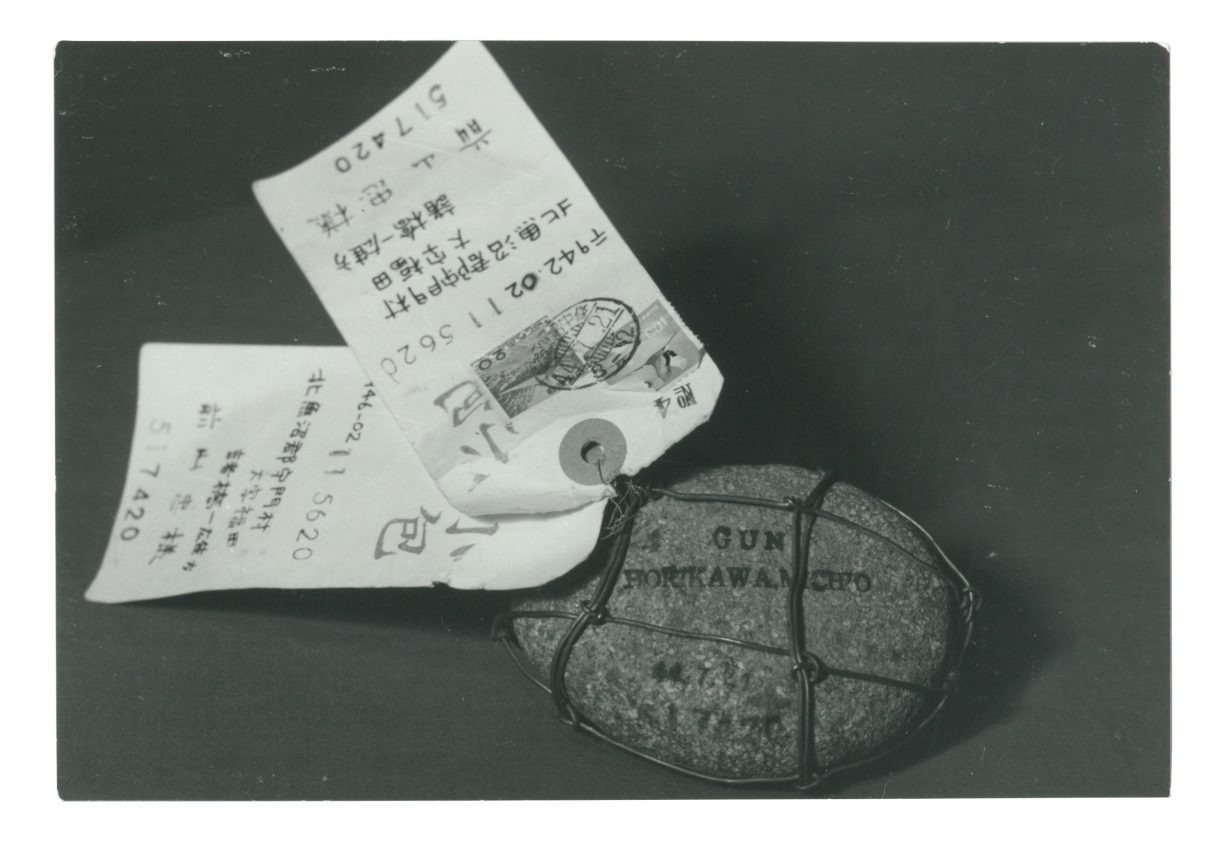

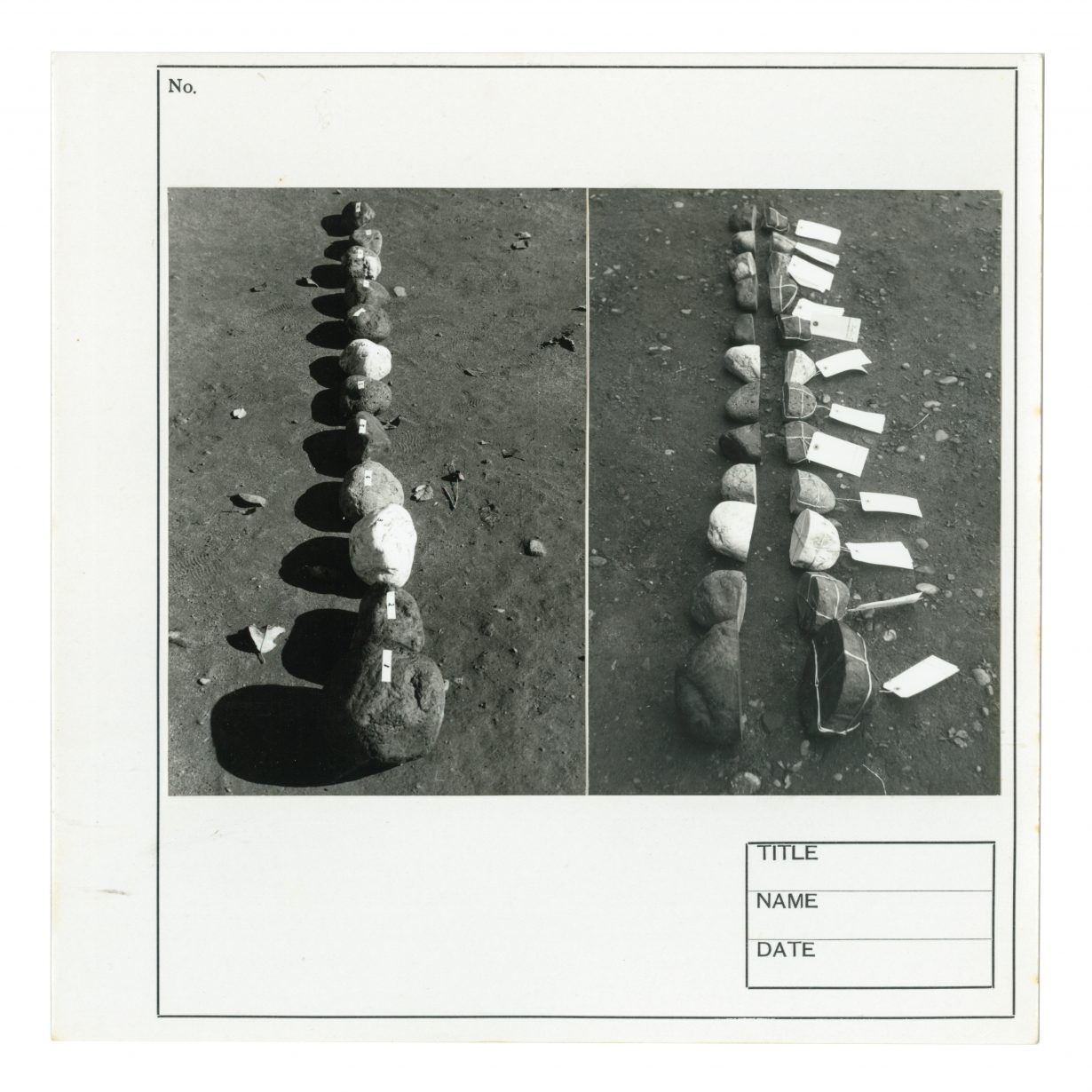

On 20 July 1969, Horikawa Michio took students from his third-period art class on a walk to the Shinano River, Japan’s longest and widest, where they collected stones from the dry bed. The artist stamped 11 stones, bound them with wire and proceeded to the post office with the intention of mailing them unpackaged. Tags were attached to the wire of each stone, addressed to 11 art critics and artists, including Horikawa himself.

With this gesture alone, Horikawa could have secured a place in the annals of mail art, but the timing of this act was what truly distinguished it. While collecting stones with his students, the artist tuned a transistor radio to a live transmission of the Apollo 11 team gathering rocks on the moon. His stamps and tags included the date and time when Neil Armstrong took those fateful steps. The first lunar landing in human history was the start of Horikawa’s unexpected lifework: Mail Art by Sending Stones.

The Apollo programme would launch six more missions over the next three years, and on each occasion, Horikawa collected and sent river stones. The artist, in his own words, sought to be ‘in conjunction’ with the programme, using the earthbound materials at his disposal. As art historian Reiko Tomii writes in Mail Art by Sending Stones: A Reader, her 2022 book with Horikawa, this manner of working set him apart from a contemporary like Lee Ufan – who faulted Horikawa for turning stones into conduits of ideas, rather than respecting their ‘stone-ness’ as his own practice endeavoured to do – and closer to the conceptual work of artist Jirō Takamatsu. (The performance Stone and Numeral, 1969, involved Takamatsu numbering a couple of hundred stones in the Tama River.) Indeed, Horikawa’s ‘conceptualist stones’, as Tomii terms them, are inseparable from the events that inspire their distribution.

Shortly after sending the first 11 stones, Horikawa published a text titled ‘Thinking on Human Travels to the Moon’ in a student newsletter. ‘I am not interested in rocks on the moon’, he provocatively begins; rather, we should ‘change the foundation of our thinking’, ‘think of a world that envelopes the whole universe’ and ‘think about the physical existence of humankind’. Horikawa cautions against indulging in postplanetary imaginaries, anticipating a critique of technoscience that would become prominent in later decades. For instance, in her 1986 essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, Ursula K. Le Guin distinguishes her science-fiction novels from triumphalist accounts of modern technology. Her books are ‘full of space ships that get stuck, missions that fail, and people who don’t understand’; however far her characters venture, they remain stubbornly human. More recently, artist Martine Syms pushed back on Afrofuturist optimism, arguing that the ‘dream of utopia can encourage us to forget that outer space will not save us from injustice’. Her ‘Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto’ (2013) challenges us to imagine that ‘Earth is all we have. What will we do with it?’ Horikawa himself, in an afterword to his book with Tomii, laments that since he began his project space exploration ‘has expanded from peaceful applications to the idea of space forces’ and luxury trips for billionaires. More than ever, he seems to suggest, we should focus on our planet and put ‘progress’ in the service of its betterment.

The Sending Stones reader begins with Horikawa’s generous chronicle of his practice from 1964 to the present, which reports when and how he made his work, the artists he was studying, the museums he visited and even some personal troubles. A few weeks before the Apollo 11 moon landing, the artist was hospitalised with a case of urinary calculus – effectively, calcified stones. When I spoke with him about this episode, he remarked that at the time “the news reported that Neil Armstrong was heading to the moon, and one of his missions was to collect rocks”. The timing was painful and priceless: to be stuck in a hospital bed with little else to do but imagine the stones on the moon, the stones of the earth and the stones painfully moving through his body.

Horikawa’s chronicle is a testament to the relational quality of mail art. The 13 stones marking the Apollo 13 mission, The Shinano River Plan (for peace of world) (1970), were sent once a day in consideration of the load on the local postman. Two stones from the first mailing went to artists Takamatsu and Yutaka Matsuzawa, Horikawa’s avowed influences. Rather than reference this debt through the coded protocols of conceptual art, Horikawa formally invited them into the circle of the work. Influence became animated through the distribution of stones. Networks were built.

This sense of relationality extends to nature itself. To make The Shinano River Plan: 12 (1969), during the Apollo 12 mission, he split 12 stones into halves, some to be mailed and others returned to the riverbed. In seeming contestation of the one-way logic of the ready-made, his stones both transmogrified and didn’t: where one half of the stones grew stamps, tags, data cards, documentation, etc, the other ended where they began, in the Shinano River. Seen from this perspective, Mail Art by Sending Stones may connect to histories of stone appreciation. Writing during the Tang dynasty, musician and poet Bai Juyi wonders if ‘the Fashioner-of-Things revealed his intention’ in the ugly and grotesque rock. ‘Jagged and notched, it really has no talent’, his contemporary, poet Lu Guimeng, observes, ‘[a]nd yet its appearance is valued by all under heaven’. This object wasn’t turned into art by the discerning eye of the scholar; it was recognised as an example of nature’s artistry. And when prevailing opinion changed, as during the Cultural Revolution, the poem that had been inscribed on a stone’s base was effaced, and it could be returned to the land in the hopes of passing as a mere stone.

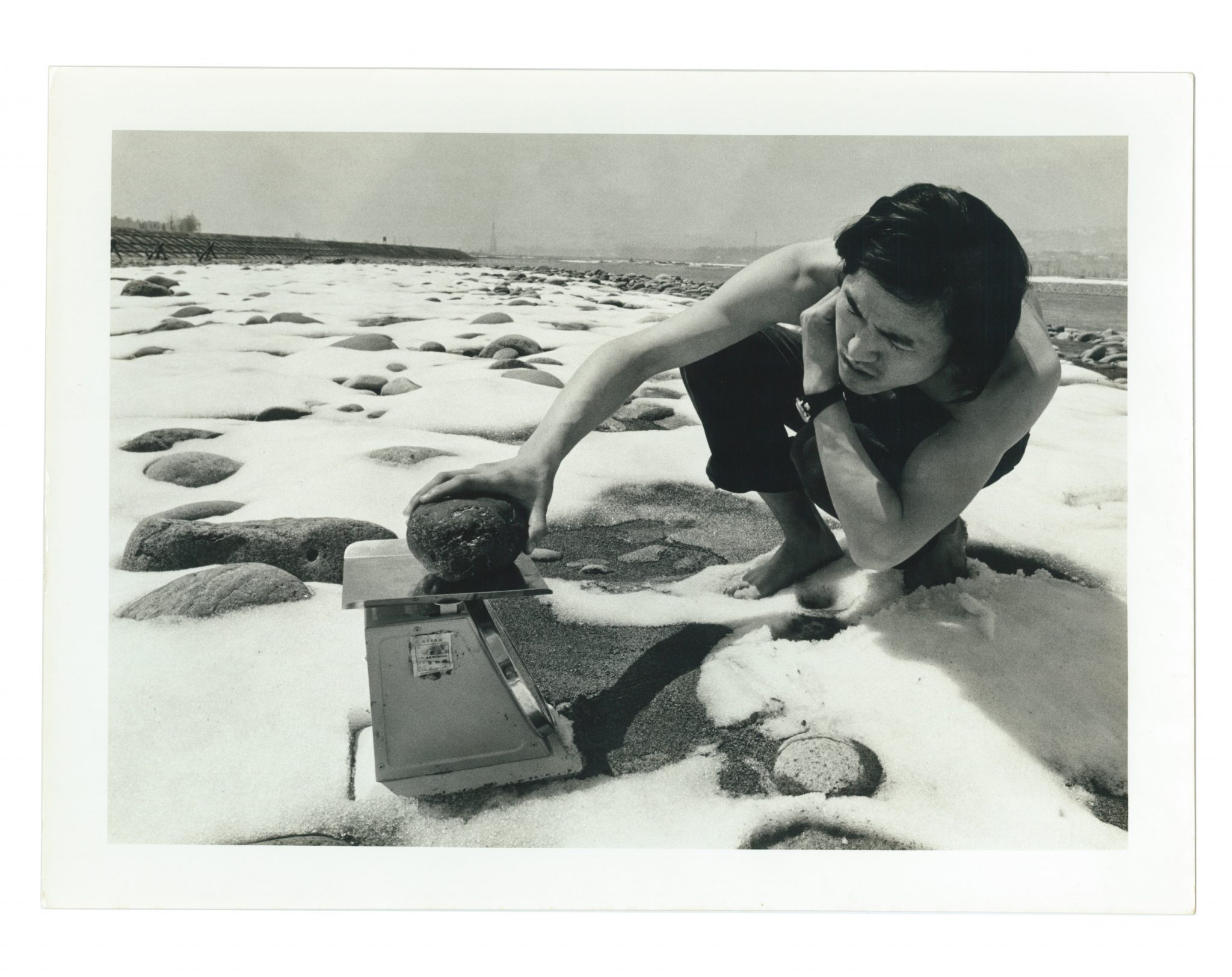

Japanese suiseki, like Chinese scholar stones, are often found in rivers and lakes, sculpted over time by natural actors to resemble landscapes in miniature. In my research, I’ve found no indication that the Shinano River is a popular destination for petrophiliacs; Horikawa may be among the few to confer value to its riverbed, though his aesthetic criteria are somewhat particular. Stones at Tokyo Biennale ’70: (13 – 4) + 9 + 9 + 9, his 2023 exhibition at Misa Shin Gallery in Tokyo, includes a slideshow of the bare-chested artist weighing stones, seeking one of approximately 300g – a parameter he set during the Apollo 11 mission. In one slide from this work, The Shinano River Plan (for peace of world), the artist flashes a peace sign in apparent solidarity with the anti-war movement.

One stone Horikawa selected went to Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Satō. A coal-coloured stone had arrived at the White House five months earlier, on 24 December 1969; both the reader and the exhibition include a note from the American ambassador in Tokyo thanking the artist, on behalf of President Richard Nixon, for ‘a most unusual Christmas gift’. These mailings add a political dimension to Horikawa’s project, their stones thrown in protest (albeit at the speed of the post). If anyone deserved getting coal in their Christmas stocking, it was Tricky Dick.

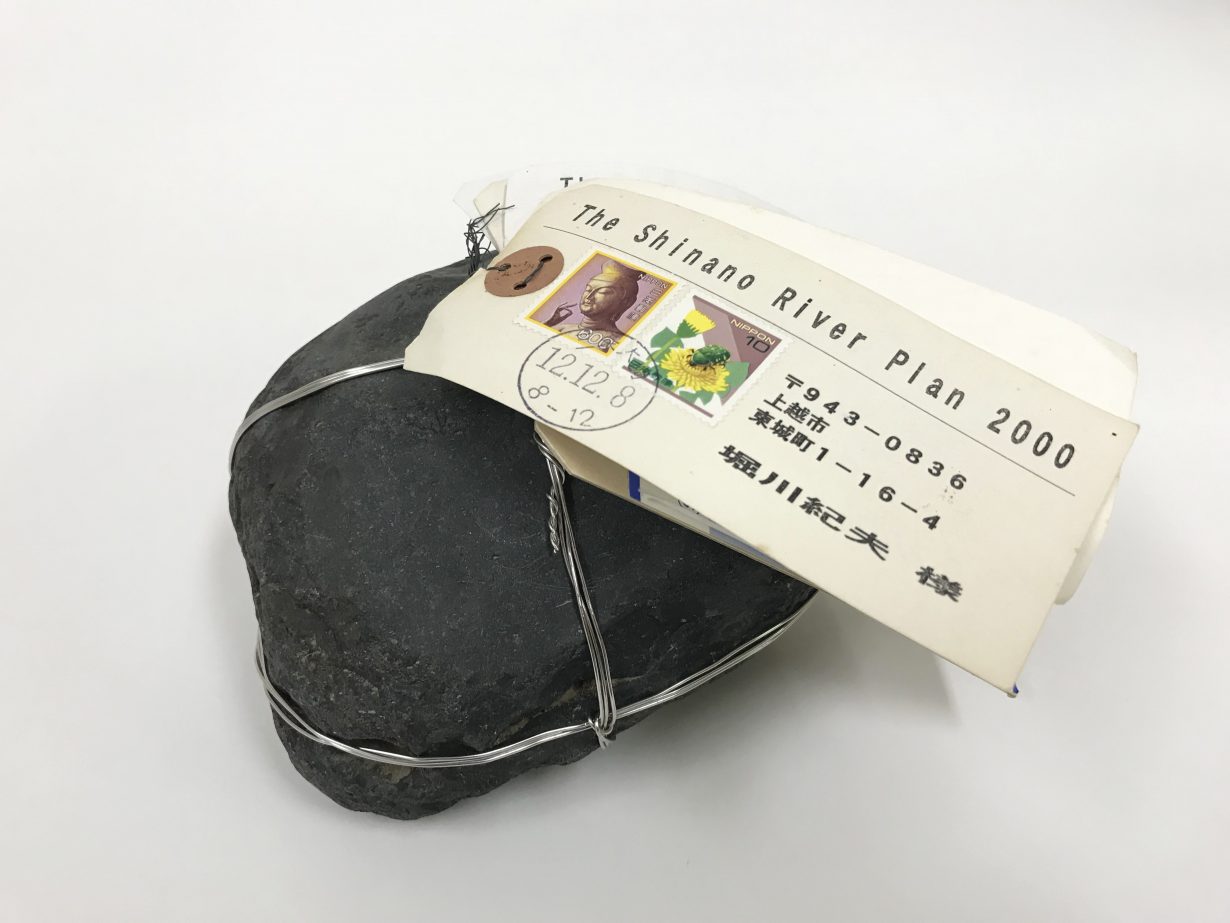

Horikawa paused Mail Art by Sending Stones after the final Apollo mission in 1972. Four stones were sent in 1985, but the project didn’t really resume until Tomii invited him to participate in Century City, a 2001 exhibition at Tate Modern, in London. For this occasion, Horikawa posted three stones: to Tomii, the museum and himself, on 8 December 2000 – the anniversary of the United States declaring war on Japan. As with past mailings, the tags of The Shinano River Plan 2000 (2000) provided some context, one reproducing a 1941 frontpage of the New York Daily News reading ‘JAPS BOMB HAWAII’, and another tag stating ‘No more HIROSHIMA / anti-War / No more NAGASAKI’. The artist began his project by sending stones in conjunction with current events; here, the logic of conjunction took a different form, rematerialising a pivotal moment of the past, on the anniversary of its occurrence, lest it blur or dull in our memory.

Horikawa has mailed many stones over the course of his career, but only in some cases was he informed of their receipt. A message can’t demand or even assume a response. The life his stones will lead, upon reaching their senders, is uncertain. And so, any news, even decades late, has the power to continue to animate Mail Art by Sending Stones. In the runup to his Misa Shin exhibition, Horikawa found one of the Apollo 13 stones in a box in his brother’s house. Separately, I contacted The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, discovering that the ‘Christmas gift’, stripped of its tags, was being stored there. Given Nixon’s obsession with recording the goings-on in his office, it’s unsurprising that anything related to his life would be kept – even a river stone received in 1969. “It seems”, Horikawa told me, “that my project has a story which lives on after my stones have been sent.”