How American writers are using erasure and redaction to expose power

What at first may seem like a playful way to generate amusing accidents of language, erasure is a branch of found poetry that has been used by writers to reveal sinister subtexts in everything from newsprint to novels. Some of its most inventive contemporary practitioners are Black, Indigenous and LGBTQ+ American writers who are appropriating official documents to highlight the violence and discrimination that underpins the language of power and create works that resist its domination. New examples keep appearing, at the same time as the state’s hostility towards these groups has intensified, and some of the most notable books of recent years have featured erasure in ways that are profound and original.

The Black American poet Nicole Sealey’s The Ferguson Report: An Erasure (2023) contains eight short poems across 105 pages, all of which Sealey created by redacting the US Department of Justice’s report into the 2014 police killing of the unarmed young Black man Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The unredacted words of Sealey’s poems are spaced out across the report, which sits in the background as a ghostly strikethrough text. Initially, I read the poems in fragments. Often I pieced together words across a line (‘Shaw, Mayor James Knowles’) which made for stop-start reading that felt like learning to play a piece of music. I read in jarring rhythms which dissipated when I began to memorise lines and find fluency.

I tried to read the full report in the poems but it was soon obvious that its shocking contents are flattened by bureaucratese that deliberately repels lay readers. Occasionally Sealey does lift an entire phrase, in this case from a man quoting what a police officer said to him: ‘don’t pass out motherfucker’. The poems are full of foreboding (‘Then the birds began to fly/ low and patternless’) and violence (‘men lying/ face down in the street,/ knees on their necks’) but can also be beautiful at the same time as frightening: ‘the soft music/ from the passing cars shouting/ down the soft music of their dying’. The sequence sharpens its focus with the fourth poem which makes explicit its themes:

…use of force. Force

of habit. Of nature. Force

his hand. Force in line.

Full force. By force. Show

of force. Brute force.

The final line of this poem, ‘To force/ open your door’, winds me every time I read it. Its repetitions conjure the unexamined and unabating prevalence of malevolent force in our world.

The eight poems are printed in verse format, without the strikethrough text, in an epilogue chapter titled ‘lifted poems’ that introduce Sealey’s line-breaks, punctuations and italics. The clarity of the enjambment and white space here was a relief but seeing the poems like this also felt unnecessary. The difficulty of reading and re-reading them amid the redacted report had been its own reward. The combination of the Department of Justice language and Sealey’s poems gives the book its tension and the poems were more open to interpretation without line-breaks or punctuation. My experience of putting together the poems while reading them was a minor version of the excavation that Sealey – who read the report many times and began erasing it ‘to further engage with its findings’, she says in a brief afterword – undertook to create them. The epilogue undermined that and indicated that they could have been published without the full report.

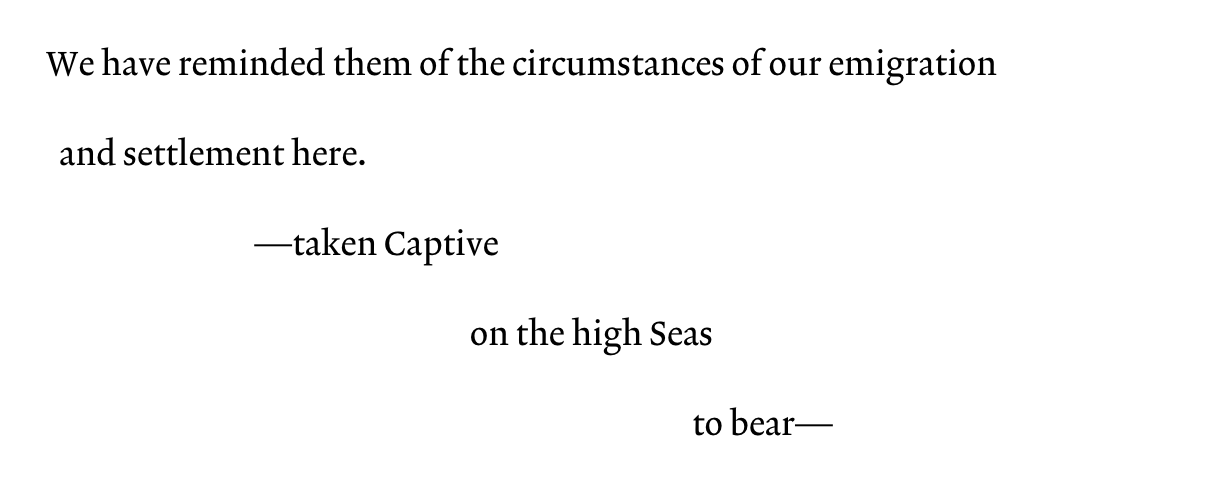

Plenty of erasure poems do appear without their foundation texts, although that is perhaps more feasible when said text is likely to be familiar to the reader already. This is true of Tracy K. Smith’s ‘Declaration’ (2018) which removes words from the US Declaration of Independence to evoke the experience of enslaved people in America:

Others have appropriated historical texts and reinstated troubling details that had been erased out of sensitivity by well-meaning people of future generations. Robin Coste Lewis’s 2016 narrative poem ‘Voyage of the Sable Venus’, for example, is comprised solely of ‘the titles, catalog entries, or exhibit descriptions of Western art objects in which a black female figure is present’, Coste Lewis explains in the prologue. Where artists, curators or institutions had updated descriptions of nineteenth-century works with modern terms such as ‘African American’, Coste Lewis ‘re-erased’ them and reinstated ‘historically specific markers’ such as ‘slave, colored and Negro’ to her text: ‘I re-corrected the corrected horror in order to allow that original horror to stand,’ she writes.

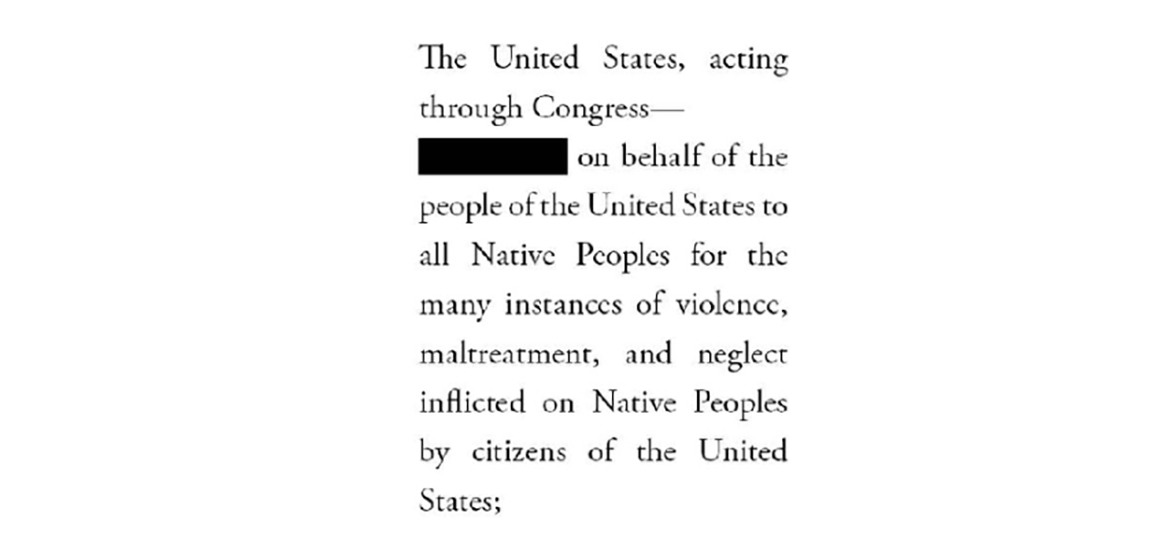

Erasure poetry in response to attempts to erase – here, white America’s excision of the Indigenous population, their culture and claims to land – is used to devastating effect by the Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long Soldier. In her prose poem ‘Whereas Statements’, Long Soldier, dismayed by the Obama administration’s official apology to Native peoples, points out that ‘in many Native languages, there is no word for “apologize”’, then presents a paragraph from the government’s apology with ‘apologizes’ redacted, showing the statement for the non-apology that it is:

With exceptions, such as Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2010 book Tree of Codes, a novel through cut-outs from Bruno Schulz’s 1933 story collection Street of Crocodiles, and Ben Lerner’s 10:04 (2014), which features the protagonist’s redacted notes for an aborted novel, American fiction writers seem to erase less than poets. But Justin Torres’s recent novel Blackouts, which won the US National Book Award for Fiction, shows its potential for novelists who want to write back into existence those who have been written out. In Blackouts, a dying old man and his young friend piece together the life of Jan Gay, a real lesbian sexologist whose interviews with gay people in the 1920s and 30s were crucial to Sex Variants, a 1941 study of ‘homosexual patterns’. Jan’s interviews showed the multiplicity of sexualities but doctors manipulated them and published edited versions that reflected the establishment view that, as one character says, ‘to be queer was unequivocally to be insane’. Torres reproduces a mysterious redacted version of the study, which the narrator and his friend find in a crumbling mansion in the American desert and spend much of the novel contemplating. The remaining words create eliptical meanings which are often erotic (‘I have not been without imaginings… carnal… unimaginable’), in effect re-queering the testimonies. At the end of the book, Torres blurs the distinction between himself and his narrator, wondering ‘whether it’s any good at all, trying to undo erasure through more erasure’ – but it is clear that he believes it is an effective technique for correcting historical wrongs.

Once you start reading erasure, you see possibilities for it everywhere. It is a deft and witty response to injustice and bad faith debates that can otherwise make you feel hopeless. ‘Pages are cavernous places, white at entrance, black in absorption,’ writes Long Soldier. Writers including Sealey and Torres encourage us to root among the black to find what it hides and reveals. Their work rewrites documents that were designed to oppress, turns the language of power back on itself and creates lyricism in the wreckage of atrocity. One day, Sealey has said, ‘the entire erasure project will become obsolete’. That day will only come when the rights of some groups to express themselves and to exist are no longer under attack. Until then erasure is a method for writers to excavate hidden pasts, shatter the silences of the present and tell stories that could form the basis for other futures.

The Ferguson Report: An Erasure by Nicole Sealey. Bloodaxe (softcover), £12.99

Blackouts by Justin Torres. Granta (hardcover), £16.99

Max Liu is a freelance journalist who contributes regularly to the i, the Financial Times and BBC Radio 4