Der Mucha – An Initial Suspicion at Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf, establishes Reinhard Mucha as one of Germany’s most estimable living artists

To grow up in Germany in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, as Reinhard Mucha did – he was born in 1950 in the city that now hosts this weighty two-venue retrospective – was to do so in a present tangled horrendously but silently with the past. Many Germans – teachers, politicians, judges – were former Nazis; still in place, too, were Holocaust-enabling infrastructure like chemical industries and, crucially for numerous artworks that Mucha would come to make, the railway network. The ‘economic miracle’ or Wirtschaftswunder that began during the 1950s had rehabilitated those supposed qualities of ‘Germanness’ (rigid discipline and willing subordination, an obsession with precision and order) that Nazism had grotesquely fetishised. And nobody was talking about any of it, or about the war. In the face of this, though, Mucha’s art over the last four decades – from small, plangent arrangements of used footstools to a full-size Ferris wheel fashioned from metal ladders, office chairs and desks and fluorescent lights, lashed together with electrical cords – is not concerned with voicing the unsaid, or not quite. It asks how you make art about, or around, what can’t ever be come to terms with, even were it to be addressed; it wonders how form might intercede with the unspeakable.

Take Dokumente I–IV (Documents 1–4, 1992), which occupies one of 15 sizeable rooms devoted to Mucha at the K21 branch of the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen. Its four highly similar parts assume his (relatively) signature form of a relief-cum-vitrine, several metres wide and hung on the wall. Each contains, decentred on the right, a wooden-framed grid of antique black-and-white photographs showing, it appears, members of a German workers’ council – representing the workforce to the bosses; one is circled and annotated ‘king’ – in 1975, and a glowing blank lightbox on the left. These elements are set, in turn, within a piece of precisely fitted-together engineering, alternating horizontal bands of steel and felt, and fetishising detail (Mucha insists on slot-head screws). Meanwhile, each glass frontage is subtly enamelled with tidy straight lines, their configuration changing from work to work like variations on a code. In one of the ‘documents’, the workers have vanished. That’s classic Mucha: making a statement of sorts, then reversing on it. For what, exactly, do we have here? An evocation of German industry and bureaucratic values, expressed in technically sympathetic facture (four pieces of industrial craftsmanship), structured partly around a beckoning white void, and taking a form that itself equivocates, landing somewhere between sculpture, 2D image and photographic archive. The longer you look, the more it slips through your fingers, by Mucha’s design.

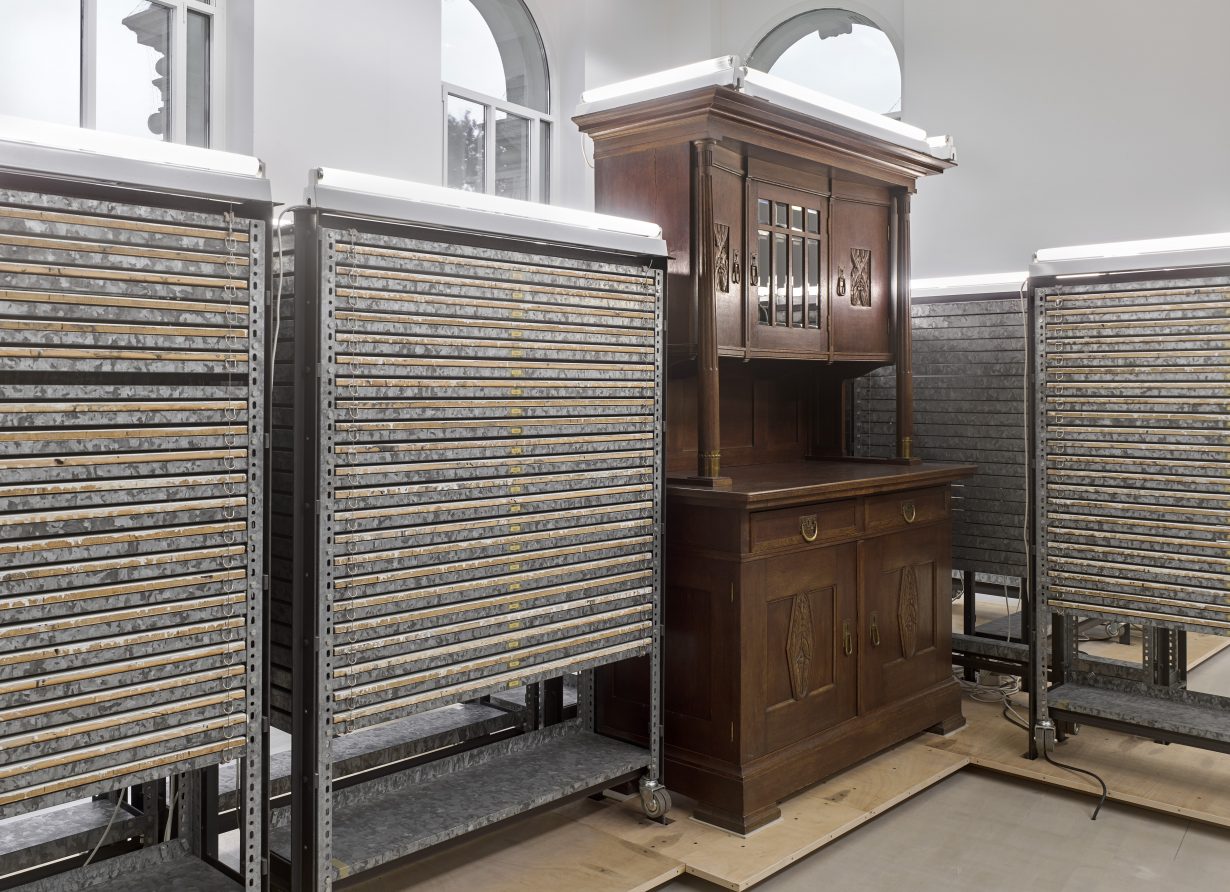

His designs, too, are subject to structural revision and augmentation when they’re re-exhibited – many of these works bear multiple dates – and accordingly resistant to being grasped. Waiting Room (1979–82), a kind of abstraction of a train-station interior, is a reconfigurable arrangement of freestanding metal sculptures that look a bit like unopenable filing cabinets, accompanied by a station sign (always a real German placename with six letters) and sometimes vintage furniture. The aesthetic template for this, as for much of Mucha’s work, is Minimalism, but of course it’s a version of the genre so pregnant with historical content that it violates Minimalism’s central tenets. In many works elsewhere, meanwhile, Mucha troubles fundamental definitions of what you’re looking at. A small work like Flak (1981) arranges various wooden items – a table, chairs, a wooden ladder – into the shape of an antiaircraft gun. What do we call this? A weapon, or German furniture, or a statement on the relationship between the two? The standout work at K20 (the Kunstsammlung’s other site), whose high-ceilinged segment is devoted primarily to Mucha’s larger works, is 1985’s two-part The Figure-Ground Problem in Baroque Architecture (for you alone only the grave remains). This combines the aforementioned Ferris wheel – an ostentatious miracle of sculptural engineering – with a full-sized fairground ‘wall of death’ made, again, from office furnishings. Both works are duckrabbits, hermeneutic escape-acts: you see tables and ladders and lights, then you see fairground attractions, and vice versa, in an endless circularity reflected in the sculptures’ shapes.

And yet, for all this structural evasiveness, Mucha’s works are somehow extremely satisfying to witness. That he is by most accounts a very complicated man is borne out in his art’s own multifariousness of register. Despite the historical shadow that hangs over this entire show, and despite its scale’s potential to exhaust a viewer, the pleasure in manufacturing, the acres of warm, well-tooled vintage wood and the undying impishness of the artist’s insistence on corrupting Minimalism with autobiography all feel redemptive. Mucha can be darkly funny while he’s frustrating you. He exhibits his own exhibition advertisements as art; are they, then? He follows a ‘what you see is what you get’ ethos insofar as all his handiwork is visible – his vitrines usually allow you to look down their sides to see how he’s put their layers together, with grandpa-in-the-workshop care – but all you can grasp, finally, is how he’s made this oblique thing. And he can be playfully absurd, as in the highly covetable kinetic sculpture Straight / Edition 1991 (2004), in which model railway trains scoot round a three-storey track, into ‘tunnels’ made out of rusty industrial piping set into a three-storey glass-fronted cabinet, while a quartet of boomboxes on top of the latter broadcast American sports commentary. Mucha has been seriously unwell of late, and Der Mucha – An Initial Suspicion (the first part of whose name refers, with characteristic evasion, not to him but to a 1980s restaurant guide from Austria) is likely his crowning achievement. It establishes, for anyone who didn’t already know, that he’s one of his country’s most estimable living artists, one who recognised both the necessity and the impossibility of countenancing Germany’s modern past. Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent, sure. Mucha found a way – found, this show confirms, many ways – to speak and be silent at once.

Der Mucha – An Initial Suspicion at K20 / K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, through 22 January