‘I just choose not to be bound by social conventions on what ‘is’ manly’: from ArtReview Asia’s Summer 2015 issue – a look at a freethinking generation of menswear designers, ranging from neon punk to cerebral elegance

What does it signify when a man wears a skirt? Or a pink bouclé jacket? Or carries a handbag? For Jean Paul Gaultier, Walter Van Beirendonck and other sexually provocative fashion designers who emerged in Europe during the late twentieth century, the deployment of totemic elements of women’s fashion in menswear has been an abiding rejection of heteronormatively-coded dress. Their velvetfrocked or rubber-skirted models perform as queer harbingers of a dreamed-of, sexually flexible future.

The deployment of skirts and genderneutral garments has recently emerged as a unifying feature in a new wave of Chinese menswear designers whose otherwise diverse house styles range from neon punk through streetwear to cerebral elegance. Rather than womenswear worn by men, the silhouettes created by Xiamen-based Shangguan Zhe, Ziggy Chen from Shanghai, Xander Zhou in Beijing and London-based Yang Li occupy a culturally hybrid space, melding character fantasy, the gloss and curiously de-eroticised gender play of K-pop, vernacular and historical costume, and an approach to gender quite alien to the binary separation of men’s and women’s garb that currently dominates ‘international’ fashion. These younger designers are not part of Gaultier and Van Beirendonck’s battle: they are less interested in exploring the territory of fierce sexuality than of gender, and gendered dress, and drawing on sources ancient and modern, classical and quotidian, as they do so.

“I don’t think my skirts or robes are feminine, nor do they have feminine shapes,” says Ziggy Chen, whose recent silhouettes are constructed from graduated layers in sobertoned, rumpled cloth: among them tilted cocoon coats, and skirt lengths ranging from knee to ankle. Drawing on traditional garments from Burma and Mongolia as well as seventeenth-century European jacket shapes, Chen’s aesthetic also makes explicit reference to ancient Chinese garments in which gender difference was expressed through surface decoration rather than shape. Far from being an outré comment on sexuality, these enveloping designs evince a conservative urge to conceal the body: “If anything,”, the designer continues, “I have never really given a thought about the concept of unisex or gender. In my opinion, garments I make don’t really fit the idea of ‘sexy’.”

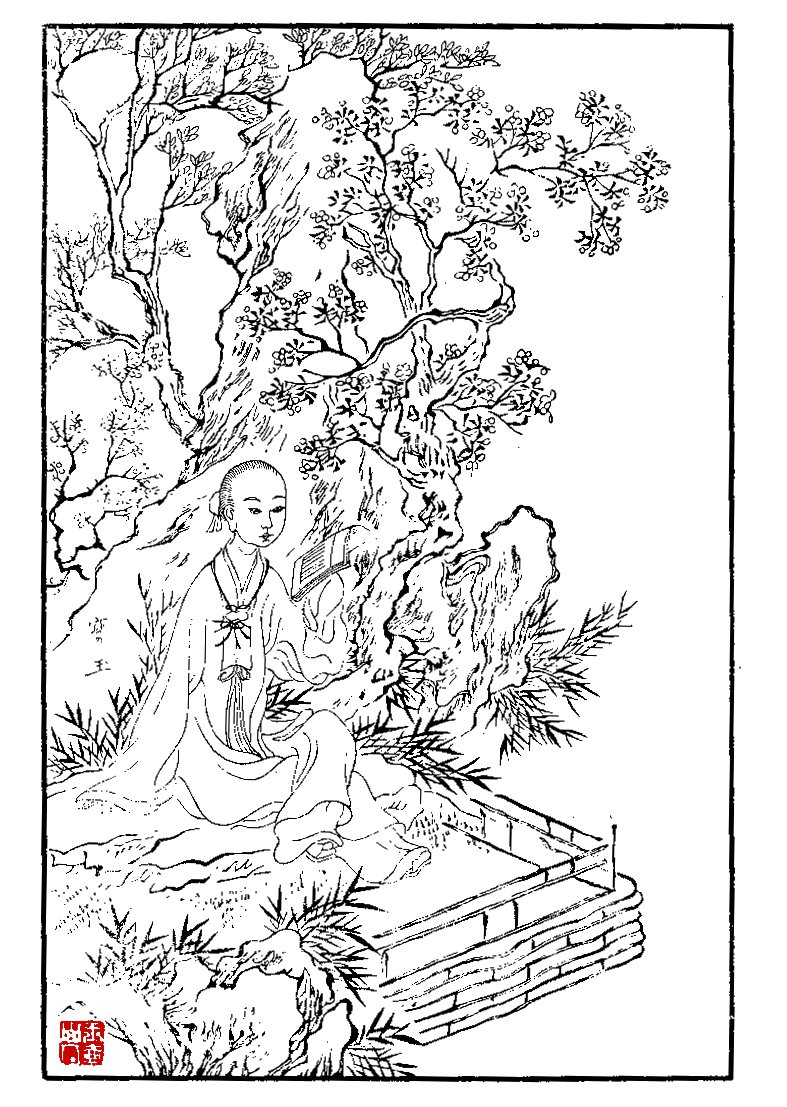

Noting that “masculine men and saucy women are less championed in Chinese culture, because they suggest barbaric behaviours and a lack of refinement”, fashion writer Tianlei Han identifies the abiding influence of nonbinary gender roles depicted in the classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber (c. 1750). “The male leading character Jia Baoyu has a feminine appearance and personality; according to Western values in the twenty-first century, he could be considered as a homosexual, but in fact, he has a wonderfully platonic ménage à trois with two women; one is vulnerable and pitiful, which raises his amour, and the other is witty and fun and perfectly fulfils the role of a fag-hag.” Han sees Dream of the Red Chamber filtering down to the plotlines of South Korean soap operas, the popularity of which in China he attributes in part to “the effeminate grooming and fashion style” of the romantic leads.

In her book Korean Masculinities and Transcultural Consumption (2011), Sun Jung identifies a trait among male K-pop idols that she terms ‘manufactured versatile masculinity’: a ‘flexible, transformable and hybrid’ male image designed for mass pan-Asian appeal that allows a single performer to display by turns feminine beauty and emotional availability, the cute but obnoxious behaviour associated with teenage boys, and a post-adolescent ‘beastlike’ masculinity. Populating soap operas and quiz shows as well as the music charts, these stars are alluring but nonthreatening, engendering the roles of child, lover and even fashion-loving girlfriend: ‘multi-layered, culturally mixed, simultaneously contradictory and most of all strategically manufactured’. Thus such (to a European observer) culturally confusing gender performance as the picture-pretty, rosebud-lipped idol G-Dragon attending the Chanel fashion show in Paris decked in a cherry-blossom-pink bouclé jacket and gamine ringlets.

Han considers South Korean pop culture to be an inescapable influence among the younger generation in China – “too trashy and seductive to resist” – whether designers care to admit to it or not, and sees its impact (together with the wide-eyed androgyny of Japanese manga) in Shangguan Zhe’s Sankuanz label. In recent seasons this theatrically inclined designer has worked closely with Tianzhuo Chen on collections distinguished by lurid motifs of penises, latex S&M masks and cartoon images of masturbation: his K-pop-bright Autumn / Winter 2015 collection produced with Ningning Jin was inspired by the fantasy of a man who falls in love with a dolphin. Sea mammal-crushes aside, Shangguan describes the “youth gender” explored in his work as “subtle” and “complex” rather than anything easily defined by “physiology and sexual orientation”. In this recent collection he imagines the Sankuanz man as having “the body of man, the body loves woman, but inside he is a woman, a lesbian playing the role of man”. This feminine interior comfortable in a masculine body explains the nonchalance with which the Sankuanz man wears a jersey dress, as if he might just be popping off for a spot of skateboarding, or a cup of coffee. Using traditional garment shapes as a calming offset to more avant-garde elements, the ungendered quality of Shangguan’s clothes is often the quietest thing about them – the knee-length robes softening the assault of graphics inspired by South Park or prison tattoos.

Since 2010, Shanghai-based blogger Timothy Parent has documented the emergence of homegrown Chinese fashion on the street and the catwalk in ‘chinesepeopledoyou style’. Through strands such as ‘The Murse Project’ he has explored stylistic phenomena that might offer a particular gendered or sexual statement in a European or North American context (such as men carrying women’s handbags) but another on the streets of Shanghai. “Men like carrying women’s purses as a way of being chivalrous and showing masculinity,”explains Parent. “Their identity goes through the female to become more masculine.” In a domestic fashion industry that dates back less than 20 years, Parent sees the emerging generation of designers as “very free” in the way they design, rejecting not only “their own geographic boundary” but also the “constructed boundary” of gender.

“I subscribe to the idea that commonly perceived gender differences are largely social constructs,” explains Xander Zhou, whose menswear collections centre instead on subcultural codes associated with the beach, scout hut or street corner. “It’s not about making my menswear androgynous. As a designer, I just choose not to be bound by social conventions on what ‘is’ manly or masculine. I think most of the people who wear my designs do not rely on clothes to define their sexuality.”

But sexuality is an abiding fascination in European menswear: this next season’s collections from Milan were distinguished by the resurgence of ‘feminine’ styles for men, while in London unabashedly queer designs by J.W. Anderson and Sibling still have the ability to provoke. The impact of a Chinese menswear aesthetic can already be felt in the cut and drape of work by European and North American designers including Craig Green and Rick Owens, but in their hands the once gender-neutral becomes eroticised through the use of tight silhouettes that emphasise body shape, and flesh-displaying apertures (which in Owens’s case even partially exposed the penises of his models). What a skirt (or a handbag, or a Chanel jacket) implies on a chap in Paris is still very different from what it signifies in Shanghai.