$1000 face masks epitomise an industry consumed by systemic inequality, unchecked consumerism and waste

Back in the swirling mists of time known as April – amidst the lockdown of mass gatherings around the world – a face mask by designer Virgil Abloh’s luxury streetwear brand Off-White, priced at more than $1000 on the fashion retail website Farfetch, became the subject of outraged social-media posts. A victim of price gouging by a reseller, it was swiftly removed from the site. In the weeks that followed, commentators began warning of the danger that brands could be seen as profiteering from a health-care emergency if they were to sell designer personal-protective-equipment (PPE). So with the recent announcement that French luxury house Louis Vuitton will be launching a branded face shield, we’ve arguably reached a turning point where luxury and pandemic aesthetics are no longer uncomfortable bedfellows. The ‘LV Shield’, which doubles as a sun visor, will be available from 30 October. While the price has not yet been made public, similar items offered by the company retail for around £700.

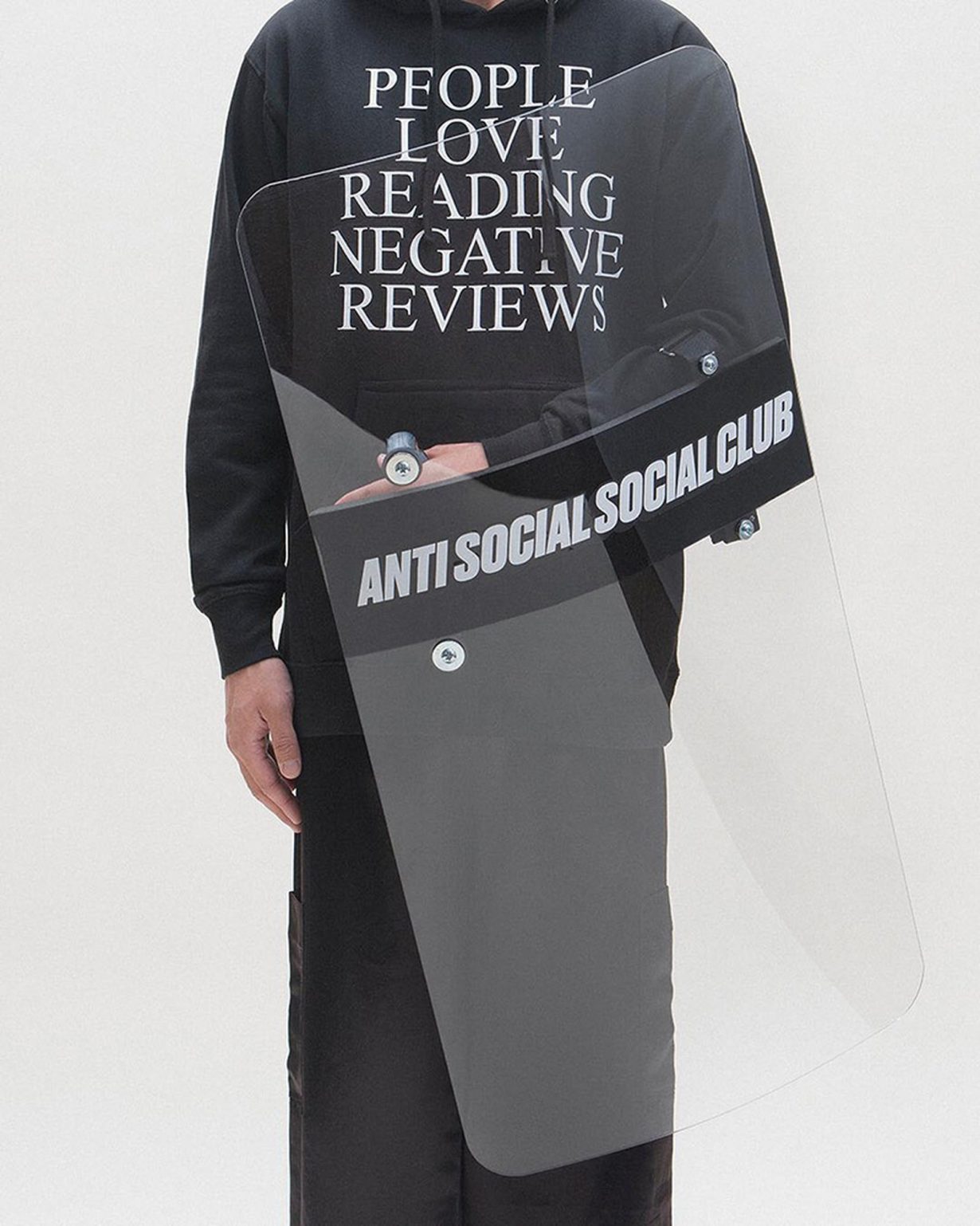

The fact that Louis Vuitton are offering a luxury version of PPE shows how acclimatised to COVID-19 the industry has become. Initial debates over whether masks should become a fashion statement have been answered with a resounding yes, from increased Etsy sales to Christian Siriano’s pearl encrusted version (Siriano was also one of the first designers to pivot to making PPE). Face masks had already become something of a trend in the music world over the past few years, while designer versions including the Off-White mask proliferated from 2018 due to a trend known as war-core: a strain of fashion that dressed for climate catastrophe and the dystopian societal breakdown of the impending apocalypse. So far so prophetic. Covering the mouth, masks are perfectly placed for non-verbal communication: a marker not just of style but also of values. And we have seen how masks have been used to make statements about police brutality, to encourage people to vote in November’s presidential election, and how even the act of mask-wearing itself has been politicised with anti-mask demonstrations across America and Europe.

Ideas around health and hygiene have always impacted how we present ourselves, and the relationship between dress and disease is complex. There have been arguments that the codpiece was developed to help treat syphilis after an epidemic began in 1494, and it’s even been suggested that trendsetters such as milliners helped to encourage inoculation against smallpox in the eighteenth century. The emaciating symptoms of tuberculosis became a beauty ideal in the nineteenth century, with pointed corsets and lightened makeup seeking to emulate the wasting effects of the disease. The current crisis has only further highlighted this intimate relationship between clothing the body and protecting it. Much of the fashion industry pivoted to creating PPE and scrubs in the early days of COVID-19. It was also inevitable that the aesthetics of the pandemic would find their way onto the catwalk.

The Viktor & Rolf show that closed the digital couture schedule this summer riffed on social distancing and lockdown dressing, with coats studded with oversized spikes and exaggerated dressing gowns. In the recent London collections, Bora Aksu presented sheer organza face masks in a collection that drew inspiration from the Spanish Flu of 1918. Designer Michael Halpern, who spent lockdown making scrubs for the UK’s National Health Service, has created a joyful film of exuberant pieces using frontline workers as models. ‘I think this moment needs joy and optimism and feathers and levity,’ he said.

But the pandemic has created an existential dilemma for fashion as we know it. It’s been argued that we are witnessing the long death rattle of an industry that is not sustainable ethically or environmentally – and hasn’t been for some time. As fashion embraced the digital world and the system reached breakneck speed, it required more and more collections to keep up with the velocity of online content and the cycles of fast fashion. Obsolescence is at the core of seasonally changing fashion: we change our clothing not because it’s worn out, but because it is no longer in style. Now with some brands considering selling unsold 2020 collections in 2021 we are faced with the question: if ‘this season’ clothing can be sold next year, what is the point in ‘this season’ at all?

This month, New York and London Fashion Weeks have been scaled down with many collections moving to online presentations. High profile editors such as Anna Wintour and Edward Enninful are not traveling to international shows, and travel bans in parts of the world are also curtailing the movement of the press. But fashion week has never been just about the shows. The extracurricular parties, events and street style are all part of a circus of fashion that has been heavily impacted. Some hope that fashion will rise like a phoenix from the ashes of COVID-19, just as Christian Dior’s inaugural collection in 1947 forged a spectacular break with the drudgery and distress of the war years, and was immediately dubbed the ‘New Look’.

It’s not an impossible dream. This year has provided an opportunity to reshape an industry beset with systemic inequality, unchecked consumerism, pollution and waste. The abuses intrinsic to murky supply chains have been exposed even further, from allegations of severe worker exploitation in Leicester, England, to brands cancelling completed orders in the wake of the pandemic, which in turn caused a humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh. This makes initiatives such as the Fashion Transparency Index – a record of brands’ social and environmental policies – created by Fashion Revolution, the world’s largest fashion activism movement, more vital than ever.

Designers – many of whom suffer from the gruelling pace of the industry – have begun to reconsider what a better fashion world could look like. In May, a number of fashion heavyweights signed an open letter asking for a slower pace, fewer and more timely seasons, and more sustainable practices including less waste and travel. Abloh, artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton as well as his label Off-White, has abandoned a seasonal schedule. Gucci has announced it will go seasonless, slashing its number of collections per year, and Donatella Versace has voiced her support for a slower system.

Further hope comes from young designers providing a desperately needed social conscience for the industry, such as the UK designer Bethany Williams who views fashion as a force for social and environmental change. During lockdown, along with Holly Fulton, Phoebe English and Cozette McCreery, she set up the Emergency Designer Network to help with PPE production. Williams incorporates her voluntary work with food banks, homeless shelters and other charities into all aspects of her sustainable business, from inspiration to production. This season she collaborated with the Magpie Project in Newham, London, with a collection drawing attention to the initiative that supports mothers and children in temporary accommodation, and 20 percent of the profits going back to the charity. All of this provides a glimpse of a future for the fashion world that prioritises care, health and a dramatically reduced carbon footprint. If this pandemic has a fashion legacy, let’s hope it’s lasting change rather than a monogrammed face shield.